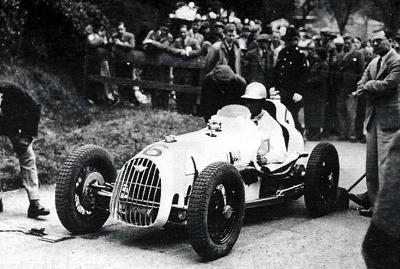

Austin Seven photographed during a British Hill-Climb event in the 1920s.

Murray Jamieson, creator of the DOHC racing cars was seen watching driver W. Baumen at the starting line at Shelsey Walsh in May, 1935. The car was a 7hp supercharged special Seven.

|

The Austin Seven in Motorsport

In August 1922, in the hands of the works test driver, Lou Kings, the Seven made its competition debut at Shelsley Walsh hill climb. Kings drove a 3.6-litre 20 hp Austin up with the creditable time of 70.2 seconds, then he snorted up in a Seven. His time of 89.8 seconds beat several 1.5-litre cars. At that time the Seven still had a 696 cm3 engine. It was bored out to 747 in March 1923.

Waite then entered an almost standard Seven in the 1923 Easter Monday Small Handicap at Brooklands and, after leading all the way, won at an average speed of 94 km/h (59 mph). He then drove the car to his home near the factory, well satisfied with the day's carefree motoring.

Waite asked for permission to take the car to Monza, in Italy, where he won the 250 km long Grand Prix des Cycle-cars, at an average speed of 91 km/h (57 mph). His victory made headlines in England and even merited a mention by the newly formed British Broadcasting Corporation whose firm policy was not to mention brand names.

The Austin Seven was mentioned by name, however, to the delight of the company. Waite celebrated by taking the car to Brooklands where it came second in the Whitsun Handicap Race, after lapping at almost 112 km/h (70 mph), a sensational time in 1923.

The

Seven was soon to prove itself very reliable at racing speeds. It was also astonishingly frugal on fuel, the unblown engines giving better than 30 miles per gallon at race meetings. A racing Seven could complete a 400 km (250 mile) race without a fuel stop.

During 1923, the car was lapping some tracks at 128 km/h (80 mph) and the factory started work on a team of three Specials, with twin carburettors, lightweight competition bodies and high lift camshaft engines. They first raced at the Boulogne Motor Week, but all three retired with

lubrication problems.

Gordon England

The early

Austin Sevens relied on a primitive system of splash and oil mist for engine

lubrication but at racing speeds the centrifugal effect of the spinning crankshaft defeated the oil flow. The problem was fixed and the racing specials became remarkably reliable. Gordon England, a well-known driver and an ingenious coach builder, did even better than the factory in modifying the early Sevens. His car was first to lap Brooklands at 128 km/h (80 mph). In 1924 he chalked up class wins at Brooklands for almost every distance in the book.

England dropped out of the picture during the late 1920s because he could not finance the development of a supercharged Seven. Superchargers were the rage in Europe at the time and Waite decided to go this route in his quest to be first to reach 160 km/h (100 mph) with a .750 cm3 engine.

His Roots-type blower, mounted in front of the engine, lifted power from 15 to 25 kW. The car's height was reduced by the use of under-slung

springs. All exposed parts were streamlined. Despite the extra power, Waite could not reach his target. His fastest run was 148 km/h (92.44 mph) achieved in one direction only at

Brooklands.

Alf Depper

Even so, towards the end of the same year - 1925 - the same car, driven by George Duller, won the 50 Mile Handicap at

Brooklands with the fantastic average speed of 144 km/h (89.9 mph). They were balmy days for

Austin. The company was making money for the first time in years and

Herbert Austin had regained full control. He gave Waite the authority to build a second blown car, this one for Alf Depper, the wiry foreman of the racing workshop.

Austin always had his own people race his cars when possible. This saved him money and was psychologically sound. He felt that when one of his cars, driven by a "bloke from the factory" won a race, the employees all shared the credit. But if the same car was driven by someone the employees didn't know, a win aroused little enthusiasm in the works.

Hector Macquarrie and Dick Matthews

In January 1927 Arthur Waite left Austin's to work in Australia with Austin Distributors Pty Ltd. He was employed there when he won the 1928 Australian Grand Prix. The first Austin Seven, landed in Sydney in 1924, had been an instant success. Subsequent imports sold steadily for several years, then took off spectacularly in 1928. The Australian Grand Prix success was not the only reason. Two New Zealanders, Hector Macquarrie and Dick Matthews, drove from Sydney to Cape York. This astonishing journey took them through tropical forests and over virgin terrain, a combination which had defeated two separate attempts by men in

Model T Fords to blaze the trail.

Most Sevens came to Australia on rolling chassis, and were fitted with local bodies.

Holden was the largest producer of bodies for Austins at the time but so many other firms got into the act that an astonishing diversity of shapes and designs appeared. It is almost impossible to find two identical Sevens in Australia.

The Wilkins-Byrd Antarctic Expedition

The Seven made deadlines again in 1930 when it survived the rigorous conditions imposed by the Wilkins-Byrd Antarctic expedition. Apart from dual rear wheels and mud chains all round, the car was standard. It was, however, the inaugural Australian Grand Prix which really put the little car on the Australian map. Waite had cabled England for his original supercharged car. As it had been sold,

Herbert Austin told the drawing office to produce a more up to date verison as quickly as possible. They did so, fitting a French-built blower to the latest 750 cm3 racing engine which had pressure fed lubrication. The car was rushed together, then taken to the long straight public road near the factory. It was clocking 144 km/h (90 mph) when the driver backed off.

Without further testing, the car was shipped to Melbourne. Waite was very disappointed when he saw that the trim lines of his original car had given way to bulbous styling. But the car went very hard - and that's what mattered. Waite had the good sense to plan his race. Realising that the track surface was uncommonly rough, he resolved to drive steadily, and wait for the opposition to bounce their way into trouble. As things turned out, Waite's car ran superbly, while the more exotic and faster machinery all gave trouble. His was the only car to complete the race without a pit stop and the Seven's average speed of 89 km/h (56 mph) was enough to humble everything, including the Type 40 Bugatti which came third.

The Austin Seven Ulster

Waite's car subsequently became the basis of a new racing and sports model, in view of its success at the Australian Grand Prix one might expect it to have been called the Phillip Island model. Instead it became the Ulster, though the best it could manage in the 1929 Ulster Trophy race was third and fourth. The production Ulster, introduced in 1928, was an open two-seater without doors. Its dropped front axle lowered the centre of gravity and the blown engine developed 23 kW (33 bhp).

Herbert Austin introduced the Ulster to enhance the car's sporting image for 1928 was the year that William Morris went into competition against the Seven.

The Morris Minor was technically superior in several respects - it had an overhead cam engine - and sold for almost exactly the same price as the Seven. Austin had good reason to be worried. More than half of the Longbridge plant's total output consisted of Sevens and he couldn't afford to drop the price, nor significantly reduce production. The firm began to rely more heavily than ever on competition success to sell cars. Investment in racing paid off. A brace of Ulsters, in the 1929 International Grand Prix at Phoenix Park, Dublin, thrilled the vast crowd with their speed and reliability. Eventually Gunnar Poppe in the leading Ulster ran out of fuel but he was so far ahead of the opposition that he pushed the car for two miles to the finish, winning his class and coming 14th overall.

A few months later, works drivers took three Ulsters to the International Road Race on the Ards Circuit at Belfast. For 27 laps, they managed to stay ahead of Caracciola in a Mercedes and Campari in an Alfa Romeo. Finally the bigger cars took the lead, but Austin drivers Nash and Holbrook still came third and fourth outright.

Sammy Davis and the Earl of March topped off the season with a fine win at the

Brooklands 500 Mile Race. Despite these successes, the factory was running scared. The MG Midget, which first began to race in 1929, had already proved it had the pace and reliability to beat the Seven.

Leon Cushman

Within two years the MG team was trouncing Austin. Waite, meanwhile, had broken his jaw in a crash during the 1930 Ulster TT and retired from active racing to manage the company's London showroom. Work began on a new streamlined Seven, with wind tunnel tests and a modified Ulster engine developing 43 kW at 6000 rpm. Driven by Leon Cushman, this clocked 163 km/h (102 mph) at Brooklands, becoming the first 750 cm3 car ever to achieve the magic "ton" in Britain. Later in Montlhery, France, Mrs Stewart covered 10 miles at an average speed of 174 km/h (109.06 mph) in the same car. A team of three, based on this design, was built and successfully raced between 1932 and 1935 by the Earl of March, Driscoll, Barnes and Goodacre.

But this was a false dawn, as the factory designers knew the writing was on the wall. The MGs were just too fast. In 1932 the decision to take on MG was made. Stan Yeal, at the

Brooklands track, was highly impressed by a white Ulster driven by a young engineer, T. Murray Jamieson. It turned out that Jamieson was employed by Amherst Villiers and was testing a supercharger of his own design for them. The upshot of this encounter was that Herbert Austin offered Jamieson a job, and sweetened the deal by buying the car and the spare parts.

Jamieson was told to produce the finest 750 cm3 racing car he could devise. His initial ideas were, however, too radical for Austin. Even though considerable design work had been done on a car with its engine amidships, the boss cancelled the project and instructed Jamieson to produce a racing car with the engine in front of the driver. The result was a beautifully proportioned miniature GP, wtih a twin overhead camshaft 750 cm3 engine. Using a 40 psi supercharger, the engine put out 90 kW (120 bhp) at 10,000 rpm. Longer than a Mini, the racer weighed a lot less, and was built on a $20,000 budget in 18 months, by three men, with some help from specialised tradesmen in the factory.

With its huge brake drums, four-speed synchromesh gearbox and superbly detailed finish, the tiny car gave rise to mammoth hopes within the factory. Unfortunately it proved unreliable - initially, at least. Jamieson had, meanwhile, clashed with some of the top factory men, many of whom were totally opposed to the project. After several bitter rows, Jamieson left the company. He lived for only a few more months being tragically killed when acting as a marshal at a

Brooklands race meeting.

Lord Austin and Charles Goodacre

By this time, Lord Austin, as he was then, had invested more money in the car than he ever intended. He recalled former company employee Charles Goodacre and asked him to quickly sort out the car. The teething troubles were quickly overcome and the magnificent looking miniature machine proved spectacularly fast. Three were built; one was written off. The first competition appearance was made in 1935, but it was not until 1937 that the machines combined speed with reliability, one reaching an incredible 208 km/h (130 mph).

The first success came in the 1937 Coronation Trophy meeting when Charles Goodacre - by now acting as driver, team manager and chief engineer - won all four races. In 1938 Bert Hadley, a works driver, made the Shelsley Walsh climb in 40.09 seconds, thus cutting in half the original Seven's time for the same climb. He also came within two seconds of the f.t.d. for the unlimited engine class. The cars kept racing until the clouds of the Second World War descended on Europe. The Austin Seven was the sensation of the 1920s and today's demand for restored or even rusted out wrecks bears this out. Less than 300,000 Sevens were built, compared with 15.5 million Model T Fords, but the survival rate is incredible.

Also see:

Austin Seven Review |

The History of Austin |

Herbert Austin |

Austin Seven Specificatons