Lotus Elite / Lotus Type 14

Reviewed by Unique Cars and Parts

Our Rating: 4

Introduction

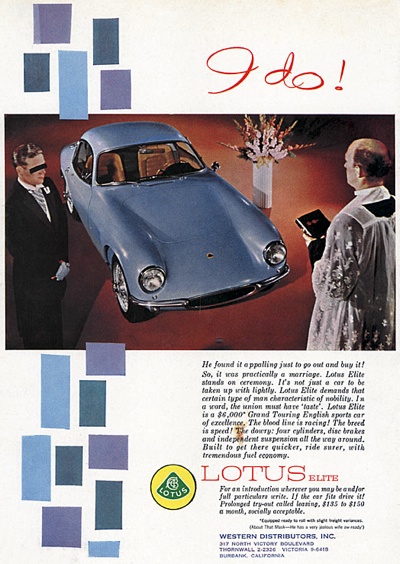

The Elite was launched in

1959 as a sophisticated and superb

handling GT and was the first vehicle to use a glassfibre monocoque comprising floor, body and a centre structure with its opening panels secured in place afterwards. The Elite's most distinctive feature was its highly innovative fibreglass monocoque construction, in which a stressed-skin unibody replaced the previously separate chassis and body components.

Unlike the contemporaneous Chevrolet Corvette, which used fibreglass for only exterior bodywork, the Elite also used this glass-reinforced plastic material for the entire load-bearing structure of the car, though the front of the monocoque incorporated a steel subframe supporting the engine and

front suspension, and there was a hoop at the windscreen for mounting door hinges and jacking the car up. This body construction caused numerous early problems, until manufacture was handed over to Bristol Aeroplane Company.

The resultant body was both lighter, stiffer, and provided better driver protection in the event of a crash. The weight savings allowed the Elite to achieve sports car performance from a 75 hp (55 kW) 1216 cc Coventry Climax all-aluminium L4 engine. Climax-powered Elites won their class six times at the

24 hour Le Mans race as well as two

Index of Thermal Efficiency wins. The overhead-cam 1216cc engine powered the car, reaching a top speed of 189 km/h. What made this vehicle unique was its quick

handling. Its front used coil-sprung damper units and MacPherson struts were used at the rear.

This resulted in excellent cornering which, luckily, was not at the expense of comfort. High specification disc

brakes were used on all wheels, and it also boasted rack-and-pinion

steering. Advanced

aerodynamics also made a contribution, giving the car a very low drag coefficient of 0.29 — quite low even for modern cars. The original Elite drawings were by Peter Kirwan-Taylor.

Frank Costin (brother of Mike, one of the co-founders of Cosworth), at that time Chief

Aerodynamic Engineer for the de Havilland Aircraft Company, contributed to the final design.

But the Elite did have its downfalls. Its shell caused a great deal of vibrating, and ventilation was also poor - it was actually impossible to wind down the windows! It was also quite pricey, being more expensive than a

Jaguar XK 150.

From The Beginning

The Elite was conceived some time in the second half of

1956, and the first example made its public appearance at the Earl's Court motor show late in

1957, arriving on the stand at the last minute, unpublicised. It was a tiny car overall, 1.2 metres high and 1.5 metres long. Compared with the then-current

356-series Porsche, the Elite was 130 mm (5 inches) longer in wheelbase - but it was almost 300 mm (12 inches) shorter, 130 mm (8 inches) lower, and 180 mm (7 inches) narrower. It used an all-alloy overhead-camshaft engine, four-wheel disc

brakes and four-wheel independent

suspension.

A heater and two-speed wipers were standard, instrumentation was comprehensive and the dashboard design impeccable (

Honda produced an almost exact replica 10 years later on the

S600). In styling,

suspension and its stressed-fibreglass construction it owed nothing to anyone. Here was a complete new approach to the high-performance road car, from a manufacturer whose total production at that time was less than 300 cars.

Three Main Mouldings

Chapman's use of fibreglass was easily justified by the very high costs which would have been required for tooling to make a pressed steel body. The fibreglass route, nonetheless, was anything but easy, since the material was then very new, and certainly no-one had ever tried to build a complete chassis with it. The ultimate solution was to produce the shell from three main mouldings. Onto a base moulding which essentially contained the undertray and inner guards was superimposed a further moulding which provided radiator ducting, and the interior surfaces of the engine bay and cockpit, while also carrying the simple steel-tube uprights serving as jacking points, door-hinge mountings and the base for the light steel tubing around the windscreen.

The distinctively Elite shape arrived with the third moulding - a one-piece shell with apertures only for essential items and otherwise completely free of joints, seams or any kind of visual or structural break. It needs close inspection to realise these three basic components don't fit closely together: mostly, they are well separated into innumerable diaphragms and small multi-sided boxes which, despite their strange shapes, give the total shell its remarkable rigidity.

Lotus Elite

|

The Bobbin Aluminium Block

There was a minimum of steel used: Apart from the scuttle tubing, the only other steel is in the front

suspension pickup sub-frame (where the off-hand crudity of the steel fabrication - normally submerged in the fibreglass - to symbolised how passionately this was seen as an all-fibreglass design). The question of how to mount heavy components in this new material was eventually solved by the Elite team with development of the "bobbin", an aluminium block, suitably drilled and tapped, and bonded in place. All the bobbin did was provide a suitable medium for bolt-attachment of components; the strength of the location was entirely a function of the fibreglass, which was varied in thickness from 1/10 in. to 3/8 in. depending on the loads involved.

But the greatest achievement, from an engineering point of view, was the success with which the Elite team, in little more than a year, was able to develop a complete chassis in a completely new medium. The Elite would not have been possible otherwise. The rapid development of the design was helped by the availability of well-proven major components. The engine was a new variant of Coventry Climax's already-successful automotive version of its FW-series fire-pump design. The stroke of the 1098 cm3 FWA (66.6 mm) was combined with the bore of the 1460 cm3 GWB (76.2 mm) to yield 1216 cm3 and in its initial specification this engine, using a mild camshaft and one 11/2

SU carburettor, delivered 56 kW (75bhp) at 6100 rpm.

The Chapman Strut

The gearbox was BMC's bulky and not-very subtle B-series with MGA ratios and remote control; the differential was BMC "A" (standard ratio was 4.55) mounted in a special Lotus casting subsequently used by the sports-racing 15s and 17s. Suspension was also largely off-the-shelf, but very much a Lotus shelf: the front

suspension used a fabricated tubular bottom wishbone of a design which carried through to the Series III Super 7 and the Formula Juniors; the combined anti-roll-bar and top wishbone was also a feature of many other late-1950s Lotus models. Rear

suspension was an application of the so-called "

Chapman strut", which used just three items - a simple trailing radius rod, a Macpherson-strut load-bearing shock absorber, and a u-jointed but unsplined halfshaft - to locate each wheel.

Peter Kirwan-Taylor

As a complete package, the Earl's Court prototype was further remarkable in how closely it foreshadowed the eventual production cars. And while regular production was nearly two years away, the creativity and intense involvement which went into that first car set the stamp on the Elite forever. Right at the centre of the development of the Elite was Peter Kirwan-Taylor, at that time a newly-qualified accountant. He had got to know

Colin Chapman well in course of assembling a Mk 6 kit (onto which he had his own design of fully-enveloping shell built), and he subsequently designed several other one-off bodies.

After the Mk 6, Kirwan-Taylor built a Swallow Doretti - one of the final 50 cars to have been made - and turned this into a sedan by removing the rear part of the body and having Williams and Pritchard build a new one to his design. A friend of Kirwan-Taylor's, with a Frazer Nash-BMW chassis, asked him if he would design a body such that he could run the car at Le Mans. Then someone else asked Kirwan-Taylor to come up with a Mk II Lotus with an enclosed body to race at Le Mans too. In a 1975 interview, Kirwan-Taylor recalled "... I went to Lotus, I discussed all with Colin, and he said I've always wanted to do that too, why don't we do it together?"

The Lotus Mk 12

That initial idea led to the Development of a whole new car, and about the only Mk II similarities which were carried over were the front

suspension and the Climax engine. In fact, as far as the

suspension went, the Elite had far more in common with the Lotus Mk 12, a best forgotten and very unsuccessful car which was Colin Chapman's first single seat design. It was the Mk 12 which first used the wishbone front suspension of the 1957 Series 2 Lotus 11s, and although first shown and tested with an 11-like de Dion rear suspension, the Mk 12 early in

1957 became the first

Lotus to use the

Chapman strut. Motoring historians contend that the Elite was originally laid out to use de-Dion rear

suspension, or it was not until several months into 1957 that an Elite rear

suspension was actually considered.

Quoting from the same interview, Kirwan-Taylor continued; "Colin is one of those people who won't just let you wave your hands and do your designing with a model. You have to do it on the drawing board. I was working all day as an accountant, and then I would work from seven 'til midnight on fifth-scale drawings and models, and that's how the car started - by translating one-fifth drawings into one-fifth models, using heat-setting clay. When this project started to get under way, first a South African appeared, then a New Zealander. The South African was Ron Hickman, who became the man who solved most of the problems with using fibreglass; the New Zealander was John Frayling, who was then working for Ford as a modeller.

John Frayling Stylist

"The car was to use the Climax engine, and the Mk 12 front

suspension. We knew what sort of weight distribution,

tyre size, bump/rebound and overall size dimensions we could work with, so we drew them in, and added a human being. It took several months of fiddling to get everything where it ought to be. We were determined to keep the frontal area to a minimum, so the Elite was designed to fit very tautly around the critical parts. The wheelbase changed several times for mechanical reasons. We were very keen on

aerodynamics at that time, and we spent a lot of time with

Frank Costin, who came in about 60 percent of the way through the project. We aimed to have no unnecessary protruberances, and we tried to have all radii starting small and opening as they went back. We ducted the

radiator - lifted the design straight off one of the racing Lotus'."

"We were very lucky in getting John Frayling. He had worked for Ford styling, but I don't consider him a stylist. He's a sculptor. Everything he did on the Elite was perfect. Another thing that made it very good was that I managed to buy a very good set of French curves. ln fact, we managed to get two sets of good curves, and that refined the shape enormously. I remember that we liked the front of the mid-1950s Ferrari Superfast, as a concept. And that we badly wanted to be able to use curved side windows, which led to making them detachable because no-one else knew anything about curved windows that wound up and down. Ten years later, when we got to the Elan and wanted to have curved side windows again it needed a lot of original Lotus work because still no-one was doing it."

A Car Without Compromise

"We designed that car without any compromises, and we really started from scratch in so many things. For example, the car had double-curvature doors but we also wanted to have fully-concealed hinges, and we wanted to be sure that everything would not just open and shut, but that when it was shut it would fit. Well ... we went round everywhere looking at the way other people hung their doors. We were a small team, and we learned by going out and looking at everything on other people's cars. What happened was we used other people's experience, and we used our ideas. The funny thing is, when we finally produced the drawings for the Elite, Colin said 'This is too dull, it's got no fire.' "

Despite it's lack of fire, Kirwan-Taylor, Frayling and Hickman prevailed. Space was rented in a shop about five kilometres from Hornsey - Lotus' headquarters at that stage - and John Frayling started work on a full-scale design, having resigned from Ford. Virtually singlehanded, he spent some four months shaping the model preparatory to a female mould being made, from which the first external shell could be taken. Quoting the same interview, Kirwan-Taylor recalled "I remember we got that first shell out one weekend, and we set it up on trestles the height it was going to be, and for the first time we cut the windows out and you couid see the car as a hollow thing, not solid. We rang Colin and told him to come down. It looked absolutely fantastic, and everyone was very enthusiastic. We decided we had to have it ready in time for Earls Court in October."

The Elite did not look like a proper car until about a week before the show. In a pre-show display, even Graham Hill was invited down to take a look. There were components left unfinished prior to its display, such as the tailshaft and much of the

cooling system. So tight was the deadline the team were working to that as the car was getting its paint-job, there were two upholstery trimmers inside the car finishing the trim!. It was ready to go about 6 am, and was the last car to roll into Earls Court.

A New Genius of Car Design

The Elite convinced the world a new genius of car design had arrived. Earlier in the year Chapman's cars had dominated the 750 cc and 1100 cc classes at Le Mans, winning both classes, winning the Coup Biennial, and dragging the Porsche team to mechanical destruction in a fight for the Index of Performance. Now it was Chapman, too, who had taken up the opportunity of fibreglass, had not merely learned a great deal about it but applied it in radical new ways, and who had overseen the whole Elite project.

But the realities of mass-production postponed deliveries of Elites until

1959, and burdened every production model with the penalties of its manufacturer's lack of capital. To start with, the Earls Court prototype incorporated a number of temporary aluminium panels, merely covered with fibreglass as a short-term measure. Frayling and Hickman, after the show, did a major re-design of internal panelling before the first selected customer cars were built. The early production models were not all that well road-tuned, such that the driveline noise would enter the cabin to such an extent as to make the cars much less appealing than they should have been.

Lotus and the Bristol Aircraft Company

By

1959 the Elite had been debugged, and financial backing had been arranged, a contract made between Lotus and a division of the Bristol Aircraft Company to produce 1000 bodies. While the early (and often specially-tuned and lightened) Elites made their mark in competition, it was the better-developed, better-trimmed Bristol-bodied cars which turned the Elite into a reality. When the magazines finally got hold of test cars, the legend moved a step further. While observing "The road manners of the Elite come as near to those of a racing car as the ordinary motorist will ever experience," The

Autocar in

1960 felt obliged to add "If it could be refined in one or two aspects it would broaden its appeal, particularly to mature motorists."

The Motor was considerably more enthusiastic. "Speed, controllability in all conditions, and comfort in all its aspects make this compact two-seater coupe an immensely desirable property for anyone who wants to enjoy big daily mileages ... The Elite is a perfectly docile runabout for shopping errands ..." The performance figures spoke for themselves: 112 mph maximum, 0-60 mph in 11.4 seconds, and almost freakish fuel consumption - 48.5 mpg at a constant 60 mph, 29.5 at a constant 100. Yet despite its high price tag, the Elite was never less than a financial burden for Lotus,

Chapman claiming the company lost money on every one.

The bigger problem was that Lotus at that time did not have the depth of resources to support the Elite. It took nearly four years to sell 1000 cars, which was very small scale - yet with the capacity Lotus had to manufacture - it was stretching things, not to mention that meant there were 1000 Lotus owners around the world dependent on a small dealer network. These issues were soon forgotten by the fortunate few owners. A car that was an instant classic? Yes - much like the

300SL - the Lotus Elite was every bit a legend rolling, ever so slowly, out of the Lotus factory and into automotive history.