THE FOUNDING FATHERS listed here at

Unique Cars and Parts seem to concentrate on the engineers, yet the reality is they represent only a tiny portion of the totality of engineering skills involved in the creation and development of the car.

Most of these famous men were engine specialists, a few were chassis designers, a handful good all-rounders, but of men who could engineer the shape of the car - as distinct from merely

'styling' it - so as to make it a better, more efficient, and (because of the functional nature of the shape) more beautiful car, there were arguably only two from the pre-1980's era.

These two were separated in age and working era by about three decades: both had a thorough grounding in aviation; and both came to work on the motor car and left it a finer concept, creating shapes that were echoed in the works of many copyists. The older was Paul Jaray, the younger was Frank Costin.

The Aerodynamicist Of The Ages

Costin today is remembered chiefly as an

aerodynamicist, the most outstanding of his time, but he was equally accomplished as a structural engineer, and remarkable for being an influential innovator in both disciplines. In articles we hare read, a common theme is that Costin was a shrewd and solitary thinker.

Wikipedia sums up the Frank Costin story very quickly - "...Costin was an automotive engineer who pioneered monocoque chassis design and was instrumental in adapting aircraft

aerodynamic knowledge for

automobile use. He was the brother of Mike Costin, co-founder of Cosworth. Frank Costin used his aeronautical knowledge to design and build a chassis from plywood. This led to a lightweight, stiff structure, which he could then clothe with an efficient,

aerodynamic body, a huge advantage in low-capacity sports car racing of the immediate postwar period."

Working with Supermarine, Percival and de Havilland

Born on the 8th June 1920, Costin's aircraft experience following World War 2 included working with Supermarine, Percival and de Havilland, including an important spell as an aerobody flight-test engineer in charge of the experimental department. It was while he was still with de Havilland that he began to seek recreation in motor sport, and this interest led to an association with

Colin Chapman, the proprietor of the then-tiny Lotus firm making some clever but small sports cars.

The Lotus Costin

The Lotus of the early 1950s, typically the Lotus 6, was a petite piece of mechanical gossamer, but about as aerodynamic as a barn door; with the body he designed for the next production model in 1954, the Lotus Costin transformed it into an arrow, obtaining for it so much extra speed that Chapman was encouraged to pursue more thoroughly both suspension design and competition honours. Thus began an involvement with the motor car that was, within three years, to earn Costin the greatest respect among those cognoscenti who could identify his work, though he enjoyed little public credit for it.

The Lotus 9

The Lotus 9 followed in a year, and, in 1956, came the svelte Lotus 11, a creation so refined that Costin's attentions went even as far as the driver's seat height: airflow tests established whether a driver's head was low enough for laminar flow to be maintained over the headrest fairing, or high enough to cause turbulent flow. Sometimes it was critical to within half an inch of helmet movement, but Costin was a precise man, and the Lotus 11 was a precision instrument: it did well in major events, notably Le Mans and Sebring and, in time, became the Lotus 15.

The Basket Case To Brilliant Vanwall

By then, Costin had produced something even more remarkable. This was the Vanwall, the crude Cooper-framed

Grand Prix sow's ear that Costin and Chapman were consulted about in the hope that it might be made into the silk purse of metaphor. Its engine was promising, but the rest a basket case. Chapman took on the chassis and created an entirely new structure. Costin assisted him on the chassis (there was nobody quicker to spot a redundant tube in a spaceframe) and created a superb body. It was breathtaking, windcheating, like nothing else on four wheels - which, in view of the state of the art at the time, was almost an assurance that it would be right.

As with most of Costin's masterpieces, it was perfectly reasonable according to the knowledge of the time, but extremely advanced according to the practice of the time. Costin's brief was a difficult one. He knew as well as anyone that a square foot of frontal area was worth yards of

streamlining, but how could he reduce the frontal area of a car whose chassis was immutable and whose height was almost incredible? The engine, set well forward, rose 26 inches above the ground; the driver, sitting above the transmission, rose 24 inches higher still. So a long nose was necessary in order to achieve that pointed shape which guaranteed good penetration of the air; and a high tail fairing was dictated by the need to eliminate eddying behind the driver's head.

Having gone so far towards producing a good streamlined shape, it was natural to go further and enclose the suspension; and, with the frontal area thus unavoidably large, the drag coefficient would have to be at least commensurately low. This was the Costin forte, and the finished design emerged as an oddly broad and bulbous shape which was nevertheless superbly smooth and curvilinear [Meaning: (Mathematics) consisting of, bounded by, or characterized by a curved line]. But not all of Costin's projects succeeded; in 1957 Maserati badly misinterpreted his brutal but elegant coup body design for their Le Mans car, its dismal performance was as nothing to Costin's rage.

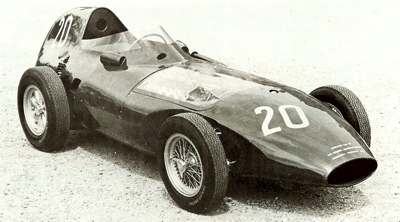

1966 Formula Two Protos. The contours were revolutionary at the time, giving the car and incredibly low drag coefficient.

1966 Formula Two Protos. The contours were revolutionary at the time, giving the car and incredibly low drag coefficient.

Arguably the most famous of the Costin designs was the Vanwald, a basket case that Costin turned into a Masterpiece, and world beater. Arguably the most famous of the Costin designs was the Vanwald, a basket case that Costin turned into a Masterpiece, and world beater.

The aerodynamics of the Lotus 11 ensured the driver's head was low enough for laminar flow to be maintained over the headrest fairing.

The aerodynamics of the Lotus 11 ensured the driver's head was low enough for laminar flow to be maintained over the headrest fairing.

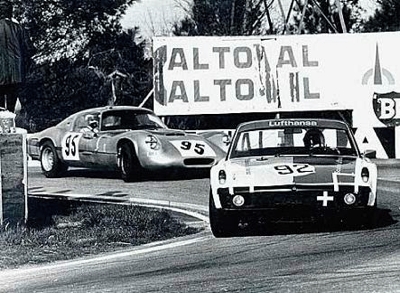

The Costin Amigo (number #95) featured wooden torsion boxes and possessed exemplary stiffness. The Costin Amigo (number #95) featured wooden torsion boxes and possessed exemplary stiffness.

This is a Ventora bodied Formula 5000 engined car, that Gery Marshall campaigned in the 1974 Super Saloon Championship in the UK. Frank Costin was responsible for the chassis design. This is a Ventora bodied Formula 5000 engined car, that Gery Marshall campaigned in the 1974 Super Saloon Championship in the UK. Frank Costin was responsible for the chassis design.

|

A Design So Efficient, It Made The Smaller Engine A Powerhouse

There were no ugly bulges on the bonnet, no inept pitot intakes for the carburettors, no vortex-generating aero screens, nothing of the impedimenta of motor-racing fashion. Instead, neat holes of carefully determined shapes were cut in the body surface at critical points where the airflow would be at relatively high pressure, and these served to admit air in the required quantities and with the very minimum of induced drag. If an air outlet were required, then it would be located where the airflow over the surface was relatively low, to induce positive extraction.

Nothing but the wheels, the mirrors, the

exhaust tailpipe and the top of the driver's head were allowed to protrude from the envelope. The result was a piece of successful trading, in which excessive frontal area had been profitably bartered for low drag: the 1957-1958 Vanwall was unquestionable, it was the fastest racing car of its time, by a margin that was quite out of proportion to the power output of its engine.

The Lotus Elite

Costin moved on to even better things. Lotus were evolving that lovely little heartbreaker, the Elite, and it was Costin's task to attend to the

aerodynamic aspects of its design. That he succeeded was amply evidenced by the distinguished competition record of the car, and by its low roadgoing fuel thirst; but how he did it makes an interesting study of applied knowledge. The Elite embodied the principle of reflex camber, one known to the aviation industry for some years (the wing section and even the fuselage of the Lockheed Constellation exemplified it well), but which Costin was the first to apply to a car.

The camber line - the mean centre line of the body section when seen in elevation - was shaped like an ogee (a double curve, resembling the letter S, formed by the union of a concave and a convex line.), drooping towards the front and rising to the rear; and Costin established that it provided

aerodynamically-induced stability at high speeds, undebased by ground effect and consistent with a body of very low drag. The Elite proved him right, and so did every car that he shaped after it.

The Speedwell Austin-Healey Sprite, Lotus Elan and British Four-Man Bobsleigh Team

Bodies for the Lister-Jaguar, the record-breaking Speedwell Austin-Healey Sprite, a special Lotus Elan for Moss, a nose for the TVR, studies for Ford, and even a low-drag body for the British four-man bobsleigh team were interspersed with hydrodynamic and structural projects for manufacturers of boats, earth-movers and printing machinery. There were also ventures in which he did more than just shape bodies: the original Marcos was typical of the situation in which Costin had often found himself, when his ability to create futuristic and effective chassis by unconventional design proved that his strict but radical logic was misplaced in business.

Not the First Monocoque, but the first Stressed-Skin Hull

The Marcos was made of wood, and was lighter and stronger than anything that might reasonably have been compared with it. Quite apart from his knowledge of engineering with wood, there was another good reason for the admirable stiffness of the Marcos frame: it was probably the first car to have what laymen wrongly called a 'monocoque' construction, and what was really a stressed-skin hull comprising a number of torsion boxes. His skill with structures brought Costin some other interesting work at about this time: the space-frame for the Lister-Jaguar (1959) was basically quite elegant, even if it needed a few diaphragms to integrate it.

The Last Time St Kilda Won A Grand Final

Monocoques figured in a chassis for

BRM and in the Costin/Nathan sports-racers, followed by a beautifully refined space-frame for a Formula 4 racer, in which two triangulated bays were joined at their apices and braced by a pair of tubes to unload the joint - perhaps the purest and simplest car space-frame ever built. By this time, Costin was itching to produce his own road car. After a streamlined, and very fast, Formula Two car, the Protos, was finished in 1966 (incidentally, the last time St Kilda won a VFL/AFL Grand Final) and proved faster than any other car of similar power, Costin settled down to design the Amigo.

The Amigo

The Amigo was typical of his work: the structure was a complex of wooden torsion boxes and possessed exemplary stiffness, the envelope shape was a minimal-drag reflex camber affair, every detail being minutely scrutinised. Even the exterior mirror was redesigned and wind-tunnel tested until its drag was halved. The whole car represented the triumph of engineering over salesmanship: it was implausibly fast (130 mph from an absolutely standard 2-Iitre Vauxhall Victor engine), ineffably competent in every kind of manoeuvre, mechanically simple and brilliantly practical, but only a handful of people could appreciate it.

The financial backing that Costin secured to cover construction of a pilot batch could not be extended to permit the car to go into production and the project foundered. Before it did, Costin was again consulted by a manufacturer of

Grand Prix cars: For the 1971 March 711, he revived

streamlining techniques that had been perfected in the days when aircraft flew as fast as racing cars travelled, producting contours calculated to minimise drag, while also negating any possibility of lift or instability in yaw, by the adoption of reflex camber.

With the nose cleared of radiators, it admitted free

aerodynamic treatment, the contours reflecting known laws - as did the diaplane or transverse wing mounted above it, the first on a car to embody the elliptical platform which echoed lift distribution and thus, most efficiently, reconciled maximum lift with minimum induced drag. The only real short-coming of the shape was that the front diaplane proved unusually sensitive to the wake of any car it was following closely. This meant that although the car could vindicate its

aerodynamic design when testing in the absence of other cars, it was handicapped in competition.

Bill Blydenstein V8 Vauxhall Ventora

These problems did not affect Costin's V8-engined Vauxhall Ventora built by Bill Blydenstein. The shape was substantially fixed by the rules under which the car was to race, and most of his work was on the chassis and suspension with a neatly mounted de Dion rear axle. The car was destroyed in an accident before it was fully developed, but not before it had shown that Costin had built yet another winner.

Costin is not involved only in racing cars, though: a decade ago he designed and built a lightweight shopping car that turned the scales at a trifling I641b, and he has resumed the quest for frugal motoring in what he describes as the 'ultimate economy human surface transport'. On the evidence of his past achievements, it will be awaited with interest; there is no doubt that it will include exciting features.

In his later years Costin continued work as a consultant, modifying the body of a Formula Ford single-seater racing car for enhanced performance, and creating his own ultra-light Dragonfly glider in conjunction with his old friend Duckworth. His early days of Olympic-standard swimming had given way to gentler pursuits, including composing music.

Many remembered

Frank Costin as a man who would not suffer half-baked projects gladly, and he was never afraid to speak his mind if he disagreed with something. He was a dedicated nonconformist, and more often than not he failed to receive the credit and recognition that were his due. Those who knew him always spoke fondly of the kind, warm-hearted man sometimes hidden within the hard outer shell with which he protected himself from the many disappointments he suffered in the ethics of his motor-racing colleagues. Frank Costin passed away on the 5th February 1995 - and on that day the world lost one of the most brilliant designers - period.