BRISTOL took its name from the Bristol Aeroplane Company, which formed a car division in 1945. A small factory was established at Filton Aerodrome (near Bristol), where the company had its headquarters and where the cars were made.

It was intended from the beginning that the cars should be built in small numbers and to the very highest standards in order to exploit the skills of the designers, inspectors and craftsmen who were recruited from the airframe and engines divisions of the company.

Due to the presence on the board, during World War 2, of a director of Frazer-Nash, which, before the war, had been an agent for BMW cars in Britain, an early decision was taken to base the design of the Bristol upon the immediate pre-war products of BMW, from whom drawings and know-how (particularly that of their distinguished engineer, Or Fiedler, were available.

There was, at the time, some criticism of this choice, though it failed to take into account that the new Bristol embodied the best features of the BMW 326 chassis, 327 body and 328 engine. The entire design was subjected to minute scrutiny and considerable revision, the metallurgical improvement being especially noteworthy.

Better still, the Bristol designers started from scratch, undertaking a detailed study of the scientific aspects of roadholding and handling, acquiring within a couple of years greater understanding and mastery of these than many other design teams in the industry. The result was that for a decade the controllability of the Bristol, its ride, handling, and cornering power, were of a standard only matched by outright purpose-built competition cars and certainly not rivalled by anything of comparable luxury.

The first Bristol, the type 400, ran in

prototype form in 1946 and made its debut at the Geneva Show in 1947. It was very much a hand-built car with virtually everything, except tyres, wheels, carburettors and electrics (to special specification), being made in the factory rather than bought from outside. Many of its design features set the pattern for subsequent models. The chassis was built from very deep box-section fabrications and lay almost entirely within the wheelbase. The live rear axle, sprung by torsion bars, was cross-over pushrods.

This layout permitted the inlet ports to plunge vertically into the

cylinder head, three downdraught carburettors giving free breathing characteristics. The efficiency of the engine and the expensively made transmission combined to give the type 400 a very high performance by the standards of its time, unhampered by the lightweight close-coupled 4-seater coupe body. Numerous competition successes were earned both in rallying and racing, but the car's main appeal was as along-distance express of quality and virtuosity.

The Bristol 401

In 1949, the 400 was joined by a new design, the 401. The independent front suspension comprised a transverse leaf spring (so mounted as to be fully live) and forged upper wishbones, with the suspension and

steering geometry refined to complement the studied characteristics of the tyres. The engine was an in-line 6-cylinder, of 1971 cc displacement, employing the best aero-engine materials and crowned by a

cylinder head which gave it exceptional efficiency.

Each combustion chamber was a polished hemisphere in which large

valves were opposed; the single camshaft, in the crankcase, was connected to the inlet

valves by pushrods, and to the exhausts (on the other side of the engine) by a secondary set of Mechanically similar, it was distinguished by a body of more exemplary

aerodynamic refinement. The stylistic inspiration came from Touring of Milan, but the actual contours were developed in Bristol's own wind tunnel to create a shape of very low drag. With the same 85 bhp engine and the same gearing as before, this car had better high-speed acceleration up to a maximum of 100 mph; with a higher axle ratio, the car proved capable of over 107 mph and covered 104 miles in one hour on the Montlhery track. The body was of aluminium panelling over a steel tubular frame- work and, despite its 5-seat capacity and large luggage boot, it weighed only 1.2 tons.

The Bristol 401.

The Bristol 402 Prototype.

The Bristol 405.

Only 2 short-chassis Zagato bodied Bristol 406S' were made. It is claimed the car had almost perfect roadholding, and combined with an elegant lightweight body it made the car a delight to drive.

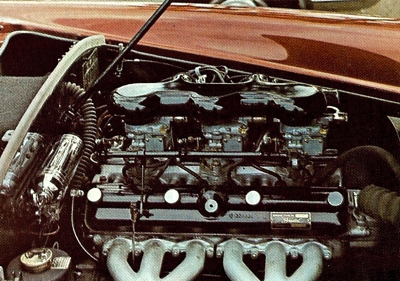

The Bristol 406 Engine Bay. The Bristol 406 Engine Bay.

The Bristol 406.

The Bristol 406.

The Zagato bodied Bristol 412 'Convertible Saloon', announced in 1975.

The Zagato bodied Bristol 412 'Convertible Saloon', announced in 1975.

|

The Bristol 402

The Bristol 402 was a drophead version, of which only 24 were made. The 403 was an evolved form of the 401, announced in June 1953; it was externally unchanged, but extensive revisions to brakes, dampers, gearbox, heating and ventilation were accompanied by improvements to the engine, which acquired larger

valves, a more sporting camshaft and a more robust bottom end, to make it capable of producing 100 bhp at 5250 rpm - still on the low-grade petrol of the time.

This engine was a detuned version of the racing unit that Bristol had been producing for some time to serve the requirements of other car manufacturers. The post-war history of Frazer-Nash was wholly based on it, and the emancipation of Cooper totally dependent on it.

By 1952, the Bristol engine of Mike Hawthorn's Cooper developed 150 bhp, sufficient to catapult him to stardom. In subsequent years this race-proved engine was sought by other manufacturers, including AC, Lister, Lotus, Tojeiro and

ERA. The G-type

ERA, a Formula Two racer, was taken over by Bristol and adapted to make the basis of the Bristol 450, when the company decided to embark on its own racing programme. Its stiff tubular chassis with de Dion rear axle and detachable-rim wheels bore little relationship to Bristol's production cars, but the engine and gearbox were essentially similar.

The Bristol body, a closed two-seater, featured twin dorsal tail fins to ensure directional stability but, in its original form for the Le Mans race of 1953, was far from clean

aerodynamically. Experimental crankshafts failed before the race was over, but not before the Bristol had lapped five seconds faster than any other car of up to two litres capacity. Reversion to a standard crankshaft made it perfectly reliable and, at Reims and Le Mans, the Bristol team of three cars won class and team awards.

Bristol Withdraw From Racing

The firm withdrew from racing at the end of the 1955 season, by which time the type 450 body had been redesigned twice- first as a very clean twin-finned coupe and then as a single-finned open car. The engine also underwent some development, the outstanding feature being a new twelve-port

cylinder head giving even better volumetric efficiency. While the 450 was still fairly new, Bristol put on the market a short-chassis luxury coupe, the type 404, which was soon christened the 'businessman's express'.

Its styling was completely new and original: the unadorned

radiator intake was based on that of the Bristol/Brabazon air liner; the two vestigial tail fins echoed those of the 450. There was a choice of engines: the touring two-litre gave 105 bhp, the sporting version, with a high-performance camshaft, gave 125. Only forty of these cars were made: not only was manufacture and inspection to aircraft standards, but the costing was done in the same way, with the result that this little car sold at a higher price than the full saloon - and newly punitive taxation, imposed shortly after its introduction, effectively killed it.

The Bristol 405

Much more successful was the 405, which reverted to the traditional 114-inch wheelbase, and carried a 4-seater saloon body with interior and exterior styling similar to that of the 404. The aluminium body had four doors (it was the only Bristol ever to do so) and, despite the use of some wood in the framework, it still weighed 1.2 tons. Mechanical revisions included the addition of an

overdrive on the tail of the close-ratio four-speed gearbox.

Among the noteworthy features inherited from the 404 was the provision of compartments in the front wings-one carrying the spare wheel, the other the

battery and most of the electrical gear; this feature which, by concentrating the weight near the' centre of the car, reduced the car's polar moment of inertia in yaw and in pitch, was continued in all subsequent models.

The 405 continued in production from late 1954 as a saloon (297 examples) and a drophead coupe (43) until 1958. By this time the British Government had enforced some rationalisation of the aircraft industry, as a result of which it became necessary for the car division to be hived off as a separate limited company. Two very interesting prototypes-one an all-independently-sprung tourer with a 3½-litre, twin-overhead-camshaft engine, the other an ultra-low super-sports car with space-frame chassis-had to be abandoned, and the new company's first production model revealed a change in emphasis.

The Bristol 406

The 406 was less idiosyncratic in appearance, much more substantial and luxurious than the already fully-equipped 405. More torque and greater flexibility were obtained by enlarging the engine to 2216 cc. The same peak power of 105 bhp was reached at only 4700 rpm. The 406 was under-rated, but it was admirably detailed. It was among the first production cars to have four disc brakes, and the first of all to have its rear axle located laterally by a Watt linkage. This perfected the

handling so much that a batch of six chassis with tuned engines were sent to Milan to be clad in lightweight four-seater grand touring bodies by Zagato. Two experimental short-chassis cars were also built.

Adopting Chryslers 5.2-litre V8

The most emphatic change came in 1961. It was clear that a much larger engine was necessary to satisfy the new demands of the market. Bristol's own new engine having to be abandoned for this reason, arrangements were made with Chrysler of Canada for a special version of their 5.2-litre V8 engine to be used in conjunction with Chrysler automatic transmission. This engine was re built by Bristol with a high-lift camshaft and mechanical tappets, as well as a number of other detail modifications, and gave the Bristol 407 outstanding performance in its class.

The car looked almost identical to the 406 but weighed 1.6 tons, and the front suspension was now by double wishbones and helical springs. Steering was no longer by rack and pinion and no longer gave the same eager and accurate responses, but the roadholding and balance were still good, and the car could exceed 122 mph with great ease in almost complete silence.

The Bristol 408

Two years later it was succeeded by the 408, mechanically almost identical, but with the body extensively restyled, particularly at the front where it now carried four headlamps. Late versions had the improved suspension, higher gearing and lighter transmission of the 409 which, in its turn, appeared in a revised form with particularly good steering. The virtues of the 407, 408 and 409 were debatable, and many customers chose to keep their six-cylinder cars and rejoice in the sensual pleasure of their

steering and gearchange, although the older models could not match the effortless superiority of the V8 performance.

The Bristol 410

The 41O, which came along in 1966, marked the point where Bristol once again could satisfy the demands of sporting customers while sacrificing nothing the sybarite might seek. All the major components were the same as in the 409 mark 2, as was the 132 mph maximum speed, but the acceleration was better, I 00 mph being reached in 23 seconds from a standing start. More obviously its roadholding was improved, the old sixteen-inch road wheels had given way to fifteen-inch ones, and a wider choice of

tyres was available. Persistent development work on suspension added up to a considerable improvement in handling.

By this time the company had been reformed: no longer a limited company, it was simply a private partnership between Sir George White (grandson of the aircraft company's founder) and Mr Anthony (Tony) Crook, an erstwhile racing driver who had been associated with Bristol since the days of the 400. Cars were still designed and made at Filton Aerodrome and a firm policy was established, that production be limited to three cars a week; no concessions were to be made to the quality of the engineering.

The Bristol 411

The expression of this policy appeared in 1969 as the Bristol 411. Still dimensionally and fundamentally like all its predecessors, but more restrained than ever in appearance, more exquisite than ever in its steering, it was more extreme than ever in its contrast of very quiet luxury with a performance that embraced a maximum speed of 140 mph with acceleration from 0 to 100 mph in under seventeen seconds. The engine of the 411 was a larger Chrysler VS of 6.2 litres, still subjected to stripping, modification and re-assembly at Filton, to give a performance materially higher than the standard Chrysler engine.

Near the end of 1970 the 411 acquired self-levelling rear suspension, with two hydraulic jacks to adjust the settings of the rear torsion bars. Wider wheels with six-inch rims carried 20SVRI5 tyres. In May 1972 the

bodywork was altered, a new front carrying four seven-inch headlamps, and this was the 411 Mark 3. The 41 1 Mark 4 appeared with different tail lamps and a larger engine in the Autumn of 1973, while the Mark 5 came along in 1975 with its different nose, restyled seats, Avon safety wheels and fog lamps. Also new in 1975 was the 412 Convertible, which was quickly renamed the Convertible-Saloon. The new car featured a targa-type roof panel and a drop-down rear hood, As ever, the car was the last word in luxury and. did no more than carry on the Bristol tradition of building 'a few cars a week properly,'

To this day, Bristol Cars has no distributors or dealers and deals directly with customers; they have a showroom in Kensington in London. They claim to be the last wholly British-owned luxury car builder. The cars have never been made in large quantities. The most recent published official production figures were for 1982 and stated 104 cars were produced that year. And unlike most specialty automakers, Bristol does not court publicity, and has only one showroom, located at 368–370 Kensington High Street in London. Nevertheless the company maintains an enthusiastic and loyal clientele. With a heritage like this, it is obvious why.