The Grand Prix of the Automobile Club de France

We have spoken in some detail on the

Unique Cars and Parts site about

Ettore Bugatti, who had one of the most fertile and original intellects in the history of the

automobile. And once again we can thank Bugatti for the alloy wheel - or, in the case of his original patent, the flat-spoked, cast, light-alloy wheel. Behind its unique appearance were engineering virtues which Ettore Bugatti himself described as:

- Good cooling of the tyre, due to the rim in aluminium, which has much greater thermal conductivity than steel;

- Fixation of the cover (tyre) to the rim by a safety ring preventing the cover being detached and all relative movement of rim and cover;

- Perfect cooling of the wheel including the brake drum.

These wheels were first seen by the world at the Grand Prix of the Automobile Club de France at Lyons, in 1924, which drew one of the largest crowds in history.

Bugatti had built six very new and important cars for this most important of Grandes Epreuves - five machines to run in the race and one to be held in reserve. These cars were the most classic of Molsheim creations - the

Bugatti Type 35. They bristled with improvements over prior Bugatti practice, including a much more reliable bottom end of the power plant, much better

brakes, an

aerodynamic body with quite low wind drag and the famous wheels.

These had yet another virtue, which Ettore Bugatti described as follows: "The

tyre shape I had adopted after making many tests, first of all on protected roads near my factory and then on the circuit itself, had given the best possible results. The construction of the cover itself and of the wheel allowed running with a deflated tyre and I thought it better to risk loss of time due to a flat tyre than to carry a spare wheel, which would certainly cause the loss of five minutes on the total time of the event."

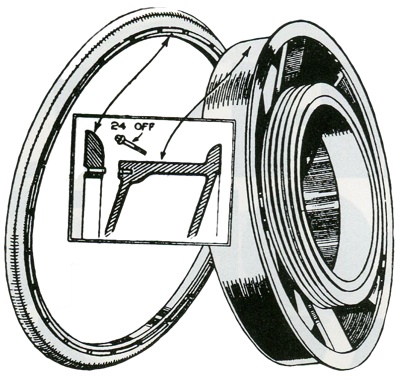

This drawing by L.C. Cresswell from The Grand Prix Car by Laurence Pomeroy shows details of Bugatti wheel, lock ring, and integrally-cast brake drum. Ferrous liners were shrunken into the drums.

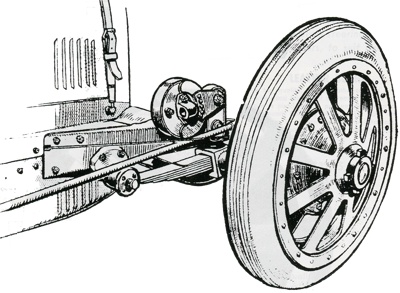

A drawing from The Autocar, 8th August, 1924. It shows what became one of the great technical achievements in automotive history, the Bugatti wheel. The spokes were not skewed and machining was easy.

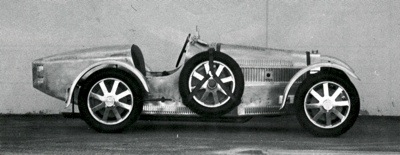

The Bugatti Type 35 in profile, the brilliant alloy wheels being arguably its greatest feature. |

Bugatti's new cars were so manifestly advanced and reliable that he had the highest hopes of victory at Lyons. This justified the most monumental logistic operation in his entire career. The cars were driven the great distance from Molsheim to Lyons under their own power but, to quote Ettore again: "I had brought to Lyons a camping installation and to give an idea to those who have not seen it, it suffices for me to say that the transport of the camping equipment was made in three railway wagons and two road trucks with trailers ... the supporting supply vehicles carried a total load of 30 tonnes.

"Everything was provided: a wooden floor under a large tent, real beds for 45 people, a shower installation, running water in each cabin, plenty of electricity. Cooking was carried out in a solid wooden hut with everything necessary to feed the personnel properly for almost a month. At the side, ditches were dug for drainage. There were two ice-boxes, one of very large size, the other smaller. There was also a caravan (a huge mobile home) for my own family . . . Everything was thus prepared for the best.

"Well prepared, more than satisfied with my drivers, happy with the choice of circuit, I believed my car the most suitable for this race. All the qualities of the 'thoroughbred' should come out in an event such as this. Accordingly, I arrived proudly at the start. I drove the reserve car and my five drivers followed with their handsome 'thoroughbreds'. The starting flag fell."

Rarely in the history of Grand Prix racing has there been a debacle to rival the catastrophe which that confronted the Type 35s on their maiden outing at Lyons, that August 3, 1924. The cars ran wonderfully well, but it was impossible to keep the treads on their rear

tyres - or such was the story given to Press and public.

In his 1948 biography of Bugatti, W.F. Bradley - who was responsible for much of the English-language reporting of the race - perpetuated this party line. He wrote: "The mistake on this occasion was in the use of a most unsuitable type of

tyre, which made it necessary to choose between throwing the treads or holding revs down. Such a mistake was unpardonable in a major race uniting

Fiat,

Alfa Romeo,

Delage,

Sunbeam and Miller." But he added: "The flat-spoke aluminium wheels proved their worth by weight reduction and improved dispersal of heat."

In The Bugatti Book and in Conway's, C.W.P. Hampton quotes an unspecified contemporary source: "In the race, using specially-made tyres, the Bugatti team had endless tyre trouble, lap after lap the five cars tearing up their covers and ruining any chance of success. But not once did the covers leave the rim, and the new wheel stood up manfully and confounded all critics."

Bugatti himself admitted that there were those who blamed his wheels as being the source of the disastrous tyre trouble. This, of course, he rejected, heaping the total blame on the miserable tyre manufacturer in question. And he quoted, in his post-race rationalisations, a letter which he got from a Mr Rapson, "the celebrated English maker of racing tyres". It reads: "I had, like you, many regrets for the bad luck that you had with your tyres in the European GP. Without these misfortunes your car would have won or have finished in the first three. The tyre faults showed up the efficiency of your aluminium wheel, which was very satisfactory. I was very favorably impressed by all the improvements that you have so judiciously made to your wheel and I think that one of the large wheel-makers in the USA would be ready to pay you substantial royalties for the manufacturing rights for that country."

Without speculating on the motives for this somewhat strange letter, it should be noted that, in the journals of the day there was a distinct sense of excitement about the promising commercial future of the newly-invented wheel. Were the flying treads caused by improper vulcanisation, as Ettore claimed, or by out-of-balance wheels, which would put the full responsibility on his own shoulders and mortally wound these commercial possibilities? The Autocar, for June 11, 1926, writing of the events at Lyons and of subsequent developments, said: "That there was a fly in the ointment was certain - with a racing car this is always the case - and this time it was the cast aluminium wheels, but this has now been reduced to the status of merely a minor defect and the car is just as desirable from the sportsman's point of view."

Vittorio Jano

This rather lame effort to heal the old wounds tells the reader that the total defects of the wheel had been reduced to the point at which only a minor defect remained. One would have to be very sporting to invest in a fast, expensive car whose wheels were admittedly defective. That race at Lyons was the greatest single event in the long life of Ing Vittorio Jano, whose brand-new and untried P2 Alfa Romeo - the dark-horse of the race - won that race and announced itself as a world-beater. I discussed with Jano Bugatti's adventure at Lyons and he told me that it was the most ludicrous thing that he ever had seen. He recalled that Bugatti had arrived with a large reserve of the new wheels, which broke one after the other and which were changed until there were no spares left. Jano was adamant on this point and he was a highly interested and knowledgable eyewitness.

The facts, as Jano had seen them, did not stop The Autocar on August 8, 1924, saying: "The very interesting cast aluminium wheels really proved their worth and gave no trouble whatsoever." One recognises Bradley's" fine hand and phrasing. Years later Laurence Pomeroy, in his The Grand Prix Car, defined at least some of the defects in the celebrated Bugatti wheel: "Entirely unconventional brake drums, cast integral with light alloy wheels, were introduced in 1924 and were, at first, a failure, as serious tyre trouble was experienced. This was due to incorrect design of the rim, and when modified no further trouble was experienced. On the later type of cars the wheels were made in one piece, but the ea.llcr models had a detachable rim held on by twenty-four small set screws. The scheme had the merit of preventing the tyre detaching itself from the wheel whilst combining wheel and drum conferred a considerable reduction in unsprung weight. It also permitted a change of brake shoes during a race at the same time as wheels and tyres were changed."

Were The Bugatti Wheels Really The First Alloy Design?

The Bugatti Alloy Wheels made their appearance in 1924, so they were obviously designed some time before that. But there was another patent that had been filed on September 22, 1919 - this patent lodged by H. A. Miller. Miller had chosen six flat spokes instead of eight and 12 set screws instead of 24. Miller entered the automotive field as an inventor and fairly important manufacturer of carburettors. He first cast their bodies in bronze, then converted to light alloys, for which he set up his own foundry. He perfected a particularly strong mix which he called "alloyanum" and he was the pioneer of light-alloy pistons in the USA.

By 1917 Miller was building "all-aluminium" engines and the block and crankcase mass of his 16-cylinder aero engine was the largest aluminium casting which had ever been made in the USA and perhaps in the world. Before he built his first thoroughbred car he was already in the world avant-garde of aluminium pioneers. This experience served him well during the Golden Age which he did so much to create. As far as the Miller Alloy Wheels were concerned, it seemed they never made it past the design phase - so while these may have been the first alloy wheel design, it was the Bugatti wheels that made it into production.

Patents. No 581,308 - Roue A Disque A Refroidissement

The first Bugatti patent for an alloy was numbered 581,308, and bore the title Roue a disque a refroidissement - "Cooled Disc Wheel". In his claim Ettore stated that a problem with all contemporary wheels, be they disc or spoked with wood or steel, was that they permitted "abnormal heating of the tyres". He did not explain the mechanics or the thermodynamics of this process but added that another inconvenience of ordinary wheels was "the heating of the brake drums during prolonged braking". The wheel which he proposed was intended "to eliminate as much as possible the above inconveniences and assure ventilation of the organs of the wheel".

This solution consisted of a rim and hub joined by one, two, or several discs, pierced in a manner to give the desired form to the "arms" or spokes. These flat arms had their leading edges skewed slightly outward and "the air is aspirated from the exterior toward the interior and, by its swift passage, powerfully cools the rim and the brake drum". There was in this patent no mention whatsoever either of aluminium or of casting. It said, however, "The wheel shown in the drawings is in a single piece; it may be constituted by a rim and a hub joined by arms which are gas-welded or riveted or by all other known means". The drawings showed an aparently cast wheel with inner and outer discs, pierced to create six flat spokes, as in the Miller design patent. The lock ring for retaining the tyre does not figure in this Bugatti patent, nor in the second one.

Patents. No 582,624 - Improvements To Vehicle Wheels

Patent No 582,624 was titled "Improvements To Vehicle Wheels" and, in view of what was about to take place at Lyons, was rather amazing. The claim opened with an attack upon the fragility of wire wheels. Then Bugatti said: "With cast wheels - which is to say where the disc or the part joining the rim and the hub comes from the foundry in a single piece with the rim and the hub - the already cited inconveniences also occur. This is because during the cooling of the piece the cooling produces internal stresses due to differences of contraction in different parts of the wheel."

Bugatti proposed improving cast wheels by providing them with iron struts, threaded at each end, "as in locomotive-boiler construction". The casting problems appear to be formidable but it is "a method of reinforcement of wheels cast in any metal, by means of spokes threaded at their extremities, placed in the wheel in a suitable manner in order to eliminate or reduce the stresses existent during castings". It is interesting that, at the time Ettore was filing this patent in which an inherent defect of the cast wheel was cited, he was manufacturing precisely such inherently defective wheels for his great, costly, and crucial Grand Prix debut at Lyons.

Patents. No 582,624 - Pneumatic-Type Wheel With Or Without Inner Tube

The final patent, No 582,952, is the jewel of them all. The drawings show a lovely cast wheel in cross-section, and the lock rings are there. Combining features from this and the first patent gives us the wheel which appeared at Lyon that August. But this third patent has a much more revolutionary objective. Its title is nothing less than Roue a enve/oppe pneumatique avec ou sans chambre a air - "Pneumatic-Type Wheel With Or Without Inner Tube". Bugatti's summary reads:

- Pneumatic - type wheel characterised by the beads of the tyre being placed, and powerfully retained against, the sides of the rim by any suitable device, these sides being formed to mate with the form of the beads, this hermetic mounting permitting the elimination of the inner tube.

- A mode of realisation by which the retention of the beads is effected by means of rings which also mate with the exterior shape of the beads.

- In the wheel specified in (1), the mounting of the valve at a point on the rim, the air being admitted under pressure directly into the tyre mounted in a hermetic manner on the rim.

- The repair of blowouts [and punctures] by a piece [of rubber] glued upon the inner face of the tyre, the air pressure holding it powerfully against the tyre."

So, in case anyone ever doubted that Bugatti was a genius, he invented the tubeless tyre in 1924. B.F. Goodrich takes credit for developing the tubeless tyre and seems to have marketed such an apparatus as early as 1947. The tubeless tyre, as we know it today, was invented by a B.F. Goodrich engineer Frank Herzegh, of Shaker Heights, Ohio. He applied for a patent on this very basic invention on December 14, 1946, then assigned it to his employer. B.F. Goodrich started manufacturing tyres of this type in late 1947 and had them on general sale in the US by February, 1948.

The Herzegh patent was infringed and led to important legal action. During the course of these proceedings no less than 66 prior patents for tubeless tyres were considered in the evidence. One of these patents - and a French one at that - dated from 1904. It was, after all, a perfectly obvious idea and Bugatti was a long way from being the first to have it. But the idea was haunting him in 1924. Bugatti made his cast wheels in a wide range of rim styles; the style used at Lyons could have been "tubeless" without being identical to the Bugatti "tubeless" patent. Bugatti himself told the world that he had his tyres for Lyons made very specially, which could be significant. Let's suppose they were run in the race without inner tubes. Then let us mull over these words by Mr Herzegh, from the text of his US Patent No 2,587,470:

"One difficulty heretofore is that devices proposed for sealing against leakage of air at the bead portions of the tyre have been overly cumbersome and difficult to install, have required special rim constructions or have not provided satisfactory sealing. Another difficulty with constructions proposed heretofore is that without the benefit of an inner tube the tyre wall has had to take the whole of the gradient of air pressure from inside to outside and as a result of diffusion of air into the wall has been vulnerable to the formation of blisters in the wall and separation of the embedded fabric plies from the rubber, which has led to early failure of the tyre. This difficulty has been present especially in tyres for high speed service where the heat developed from the rapid flexure of the tyre walls has caused expansion of air diffused into and pocketed in the wall, which in turn has caused or aggravated separation of the tyre material. Rubber compositions heretofore used in tyre wall construction have not provided a sufficiently high resistance to diffusion of the air into the tyre wall to prevent this difficulty in a satisfactory manner.

We can speculate today that perhaps it was the lack of Herzegh's "lining layer" (about .04 inch or one millimetre thick) that caused the disaster at Lyons and of Bugatti's abandonment of the tubeless-tyre principle.