Amilcar

|

1921

- 1940 |

Country: |

|

|

It seems nearly all motoring journalists agree that the

Austin 7 was "the" ground-breaking concept in small car design, however the first really popular small car was French, and was called Le Zebre.

The Zebre had a single-cylinder 634 cc engine until 1913, when the Zebre's designer, M. Salomon, launched his first miniature four-cylinder motor car, and it was this design which foreshadowed all the successful small cars to come.

Immediately after the First World War, the Le Zebre Company was producing M. Salomon's 4-cylinder, 55 mm x 105 mm (999 cc) trend-setter, but somehow the company had lost its impetus and the car sold only in small numbers.

However, fate - coupled with economic necessity and some inspired commercial judgment - was to allow Salomon the free rein his engineering expertise demanded. About this time, Andre Citroen found his munitions factory short of work and decided to manufacture cars.

Originally, he planned to enter the arena with a high-performance luxury machine, and preliminary work was undertaken, but his commercial acumen eventually persuaded him that success would probably be better guaranteed at the lower end of the market.

He offered Salomon far more than the small Le Zebre Company could pay, and the first result of the combination of Citroen's money and Salomon's brilliance was the 5CV Citroen, a vehicle which had the same bore as his earlier design, but a fashionably short stroke of 90 mm and a capacity of 855 cc.

The French Boom In Cycle Cars

Meanwhile, two financiers, Joseph Lamy and Emil Akar, had also realised that there were fortunes to be made in supplying really cheap transport to car-hungry France, especially as there was at that time a typically French law which permitted cycle cars - a cross between a motor cycle and a car - to pay an annual tax of only a few francs, as long as they weighed less than 770 lb.

Even then the public were prejudiced against crude belt or chain-driven cyclecars, and it was obvious that if a company could build a real car in miniature, at a popular price, profitability would be assured. Lamy and Akar were Le Zebre shareholders, but they decided to build an entirely new model, which was christened the Amilcar, from a combination of their two names.

Accordingly, they investigated the doubly unfortunate Le Zebre factory and seduced away two brilliant young pupils of the famous Salomon, Edmond Moyet and Andre Morel. Moyet designed a typical Salomon engine for the new Amilcar which, with the same 55 mm bore as the Zebre and the Citroen and a 95 mm stroke, had a capacity of 903 cc. All three of these engines featured side-valves and two-bearing

crankshafts, but the Amilcar featured a combined cast-iron cylinder and crankcase block instead of the separate aluminium crankcase of the Citroen.

In this respect, the first Amilcar followed the Model T Ford, and another similarity was to be found in the so-called constant-level splash lubrication. There was no

oil pump fitted to this early engine; the flywheel dipped into a sump and lifted the lubricant up to a cup, from which it ran by gravity to the main bearings and big-end troughs. The clutch ran in oil and was of the multi-plate pattern, coupled to a unit gearbox of sliding-pinion type, giving three speeds.

The prop-shaft drive was conventional but the rear axle had no differential. Cooling was by thermo-syphon without the aid of any water impeller or fan. Though the saving of weight was vital, this was not the only advantage to be gained from the solid axle. A very light car with bicycle-thin

tyres bounced a good deal on the war-damaged roads of France, and both roadholding and braking were found to be better if the rear wheels were denied separate movement. A single axle shaft went from one hub to the other, with the crown wheel keyed in the middle. At first, straight-toothed bevels were employed, but later a change was made to spiral bevels, in which the fitting clearances for quiet running were not so critical.

Weight had to be saved in the chassis, which was narrow and carried quarter-elliptic 'grasshopper' springs projecting from each end. These were attached to the axles, the front axle on the first few cars being of wood, for some odd reason. The handbrake worked on one rear drum and the footbrake on the other - another advantage of having no differential - and the centre-locking wire-spoked wheels carried beaded-edge

tyres of 700 mm x 80 mm size.

To keep within the weight limit and therefore benefit from lower taxation, very simple bodies of the minimum possible size were fitted, such luxuries as doors being considered unnecessary, though a single door could be obtained in the less sporting models. To reduce the space occupied by the driver and passenger, most of the bodies had staggered seats. This plan had been used in racing cars for years, the passenger (or mechanic) sitting further back than the driver and passing his right arm behind the driver's seat.

The Petit Sport or Bordino

But the arrangement also had a great commercial advantage in that it much improved the look of a very small car. It was in appearance that the Amilcar scored most, as it really was a pretty little car. One of the early body styles was called the Petit Sport or Bordino - the latter being a famous Fiat driver who was supposed to have originated the pointed tail with a vertical knife edge. Perhaps the most attractive of all was the Bateau, a skiff-type body planked in mahogany. These bodies, in spite of their simplicity and small size, were so beautifully proportioned that the Amilcar could not fail to sell.

The first Bol d'Or in St Germain

In 1922, the first Bol d'Or race was organised in the Forest of St Germain. This was an event for motorcycles and cars up to 1100 cc, which required a single driver to be at the wheel for 24 hours. Run by the former Club of Military Motor cyclists, it took place on a tricky circuit, less than 3 miles round, and was to become a classic. The race was won by Andre Morel in the little Amilcar, covering 1450 km in a day and a night. During the same year, the Automobile Club de l'Ouest held a 'Grand Prix' for 1100 cc voiturettes over 247 miles at Le Mans. In spite of their small side-valve engines, Amilcars came third and, fourth behind a couple of twin-overhead-camshaft Salmsons, which was a remarkable achievement and a splendid advertisement for the new marque.

The Amilcar Type CC

The side-valve Arnilcars were never fast, even by the standards of their day, but these results revealed their exceptional reliability. Though the original object of Lamy and Akar had been to build cars eligible for the reduced cyclecar tax, it was discovered that customers would prefer to pay the normal small car imposition if they could have a little more comfort. The type CC of 903 cc and type CS of 985 cc, the latter having a more sporting engine developing 23 bhp at 3200 rpm, could just be kept down to the limit if inadequately equipped. The C4, which had a 1004 cc engine, a hood, and even a hole in the tail for an unfortunate third passenger, was appreciably heavier, and soon four-seater bodies began to be available.

The first Amilcars had ordinary valanced mudguards and wooden running boards, but the early sports models were fitted with delicious flared guards, which may not have been very efficient at their primary job but were, and still are, unbeatable for looks when kept clean inside and out. Then came the wings which would soon always be associated with Amilcars and which, although they were not exclusive to this make, were very much an Amilcar feature. They were simply long gutters, running over the front and back wheels each side. These gutters were not completely straight but were curved down behind the front wheels gradually - just enough to give the impression of wings sweeping into very high running boards - then they rose fairly abruptly and passed horizontally over the rear wheels. The width and depth of the channel was constant throughout the length.

Now that the weight barrier had been broken, the way lay open for a more fully equipped Amilcar with a complete electrical system and, above all, four-wheel brakes. As the quarter-elliptic front springs, which were devoid of radius arms, could not absorb the torque of brakes, the chassis frame was extended in the form of dumb irons, and semi-elliptic springs were adopted. The

brakes were operated by cables and pushrods passing through the king pins, as on Alfa Romeo and Lea Francis among others. Though the cowled

radiator and bonnet were extremely narrow, the dumb irons swept outwards at the front and the springs were shackled outside the chassis at their rear anchorages, giving as wide a front spring-base as possible.

An Amilcar CGS taking part in a hill-climb, an event it was well suited to due to its inherent lightness.

An Amilcar CGS taking part in a hill-climb, an event it was well suited to due to its inherent lightness.

An Amilcar CGSs, or "Surbaisse" version of the CGS.

An Amilcar CGSs, or "Surbaisse" version of the CGS.

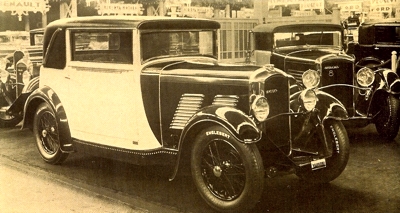

This is the Straight-Eight 2 litre Amilcar of 1929, shown here at a French motor show. It was usually fitted with a Weymann fabric body.

This is the Straight-Eight 2 litre Amilcar of 1929, shown here at a French motor show. It was usually fitted with a Weymann fabric body. |

The Amilcar Grand Sport

Thus, about 1924, was born the type CGS or Grand Sport, which is the best-known of the Amilcars. This and the lowered or surbaisse version of 1926, usually called CGSs, were very popular in England in pre-MG days. They handled beautifully, with the high-geared, direct

steering that every sports car ought to have. Indeed, they could be slid under control on wet or loose-surfaced roads in a way that, decades after the design, few cars could emulate. Sadly, it must be admitted that the weight had gone up to 11.5 cwt or so and the car had inevitably lost some of its liveliness, even though a more efficient engine of 1074 cc had been adopted, developing something in the region of 30 bhp and a little more for the Ss.

Full pressure lubrication was standardised early in the lite of this series. A supercharged engine giving about 40 bhp was also available and one of these, in a long-chassis Amilcar with a Weymann fabric saloon body, won the 1927 Monte Carlo Rally. All these Amilcars had side-valve engines and many special parts were available, which were almost essential if reliability was to be maintained in supercharged form. These included such basic items as roller-bearing crankshafts and water pumps, but the standard models, like most side-valves, were not amenable to tuning in unsupercharged trim.

Unfortunately, dishonest advertising was considered normal in the 1920s and some of the British agents for Amilcar really excelled themselves. It was usual in England in those days to describe a car by two horsepower figures, the Treasury rating and the brake horsepower on the test bench, such as the 14/40 Vauxhall or the 20/60 Sunbeam. The CGS was advertised in England as the 9/50, which was some 20 bhp too much! It was also 'guaranteed' to do 75 mph. These speed claims were absurd at this time, cars like the 1500 cc Frazer Nash being timed at a maximum of 67 mph and the Type 40 Bugatti at 65 mph - so when you read such figures on other web sites consider yourself warned on the accuracy.

The Supercharged Anzani Powered Amilcar

The honest maxima of Amilcars were 50 mph for the CC, 55 mph for the CS, and 60 mph for the CGS; supercharged 'works' cars in racing trim being much faster, of course. Some larger Amilcar engines were also made in several different sizes right up to 2 litres, but these were for 4-seaters and the saloons hat were becoming popular; they were not sports-car units. The basic strength of the chassis was proved by Ernest Eldridge, a pioneer racing motorist who fitted a supercharged Anzani engine to his Amilcar and raced it as the Eldridge Special - its

radiator carrying the famous Eldridge cowl. Towards the end of its long life, which finished in 1929, the CGS had a 4-speed gearbox.

The side-valve Amilcar was a very popular car, more than 15,000 being built in France, in addition to those constructed under licence in Italy, Germany and Austria. Nevertheless, it was unable to compete on equal terms in races (even in supercharged form) with the Salmson, which had twin overhead camshafts. Accordingly, Amilcar introduced a superb twin-overhead-camshaft six-cylinder competition car, still in the 1100 cc class. Designed by Edmond Moyet in 1925, it had dimensions of 56mmx 74mm (1097cc). Supercharged, it developed 70 bhp at 5500 rpm in standard form. With semi-elliptic springs in front and quarter-elliptics behind, it looked like a miniature

Grand Prix car.

The works cars had roller-bearing engines and probably ran at a higher supercharger pressure. The Amilcar 'six' chased the four-cylinder Salmsons off the circuits, and the new straight-eight which was to be Salmson's reply never became raceworthy. The Amilcar was one of those rare competition cars that was outstandingly successful at its first outing and remained so over many years. A specially lightened single-seater was built by the works in 1927 and won its last race - against modern cars - in 1953.

The Unreliable Straight Eight Spells The End

In 1929, the side-valve Amilcars were replaced by a new production model, the Straight-Eight. This was a low and attractive car, usually fitted with a Weymann fabric saloon body, and it had a single chain-driven overhead-camshaft and a twin-choke updraught Solex carburettor. The engine was of 63 mm x So mm (1992cc), soon increased to 66mm x 85mm (2330 cc) as the car lacked performance. Worse still, the straight-eight power unit proved fragile in the hands of the public, and it appeared it had been launched without sufficient testing, possibly for political and economic reasons. In fact a new model was imperative as the company was on the rocks. This would not normally have been a total disaster, but 1929 was the first year of the Great Depression.

In the early 1920s there had been some 350 French car manufacturers. By the middle 1930s there were only 23. In these appalling circumstances, it was impossible to go back to the drawing board with the Straight-Eight which was allowed to soldier on until it got a bad name and finally ceased production. In any case, viewed in retrospect, it was a hopeless time to introduce it, as nobody wanted an eight-cylinder car when fuel economy was the only interest. Efforts were made to re-introduce the four-cylinder models, but already the fame earned in racing had evaporated.

Frenchmen turned away from sports cars and the hundreds of little sports car factories in the Paris suburbs had no more customers. The Amilcar was one of the few small French cars to have its own engine instead of the proprietary units used in the majority of its competitors. It was also the product of a properly financed business, which was rare, but in reality a four-cylinder Amilcar saloon was no better than a Renault or a Citroen and cost more than those mass-production vehicles. The magic had gone out of Amilcar and it was soon obvious that the Great Depression had dealt the firm a mortal blow.

The Amilcar Pegase and Hotchkiss Amilcar Compound

A bigger four-cylinder model, the Pegase, was announced, but this was not really a genuine Amilcar, many of the components coming from Delahaye and Hotchkiss. The model was even raced, but there was to be no miracle. When Amilcar eventually foundered Hotchkiss took on some of the Amilcar personnel and devoted factory space to developing an entirely new car. It was called the Hotchkiss Amilcar Compound and was of extremely advanced design, with an aluminium chassis and front-wheel drive. Propelled by a side-valve Amilcar engine of 1185 cc, it could well have become a successful car, but World War 2 killed Amilcar.

Even with the benefit of hindsight, it is difficult to see how things could have been managed very differently. After World War 1, every Frenchman worth his salt wanted a little blue open sports car which looked like a Bugatti. A decade later, perhaps largely due to the serious frame of mind which was inspired by the Depression, he was no longer interested in anything so frivolous. It was commercial madness to compete with Andre Citroen and

Louis Renault in the cheap saloon market and so the apparently wise decision was taken to produce a 2-litre saloon of great refinement. Nobody foresaw that the Depression would become a world disaster, or a car of such quality would not have been launched, but it really made no difference.

The economic crisis finished all the small French manufacturers and even those that limped on for a few years found that they had sustained fatal damage. After this length of time, it is difficult for Unique Cars and Parts to ascertain whether Joseph Lamy and Emil Akar were still heavily involved, but it would appear likely that they were not. At the outset, some of the Le Zebre agents were persuaded to invest money in the new Amilcar firm by Moyet and Morel when they changed over. No doubt they, along with a great many other small shareholders, lost money - nothing unusual - at that time!

The real Amilcar achievement was to build really good-looking sports cars, perfectly proportioned down to the smallest nut and bolt, at a price which young enthusiasts could afford to pay. There were memorable racing successes, but Amilcar was, above all, another word for happiness to many young people.