ALEXANDRE DARRACQ WAS, it was said, an engineer '

by temperament if not by qualification'. Born in 1855, he worked first in an arsenal, then at the Hurtu factory, manufacturing sewing machines.

However, although a machine of Darracq's design won him a gold medal at the 1889 Paris exhibition, his natural instincts were those of a sharp financier rather than a mechanic. He was soon enjoying the bicycle boom, making cycles in a workshop in the Place de la Nation.

Later, an association with a new partner, Jean Aucoc, led to a diversion into vintner's sundries, then to the establishment of a factory in the Pre-Saint-Gervais, making Gladiator bicycles, which soon established an enviable track record, breaking records and winning races in Europe and America.

The Clement-Gladiator-Humber consortium

Hardly surprisingly, the company came into the orbit of that notorious entrepreneur, Adolphe Clement, and was one of the three companies involved in the 22 million franc flotation of the Clement-Gladiator-Humber consortium. Darracq was bought out on condition that he didn't set up as a cycle manufacturer again; so he built cycle components instead, and dodged the terms of the contract.

A brand-new factory was built at Suresnes, and a start in motor-cycle manufacture was made with the odd five-cylinder, rotary-engined Millet; but more orthodox devices soon prevailed. Darracq saw that there was a profit to be made in the horseless carriage, and moved in with an electric brougham, following with a Leon Bollee-designed voiturette.

The success of Bollee's three-wheeler seemed to guarantee that the £10,000 that Darracq paid for the manufacturing rights of this latest design was money well spent. Unfortunately, the little four-wheeler was a flop, even by the uncritical standards of 1898. Its five-speed belt-drive was a masterpiece of bad design, and the obsolete hdt-tube ignition added to the problems.

Once it was running, the curious

steering layout promised early disaster. Fortunately, Darracq soon hired another designer, Ribeyrolles, who had more orthodox ideas on car layout and conceived a handsome 6.5 hp

uoiture legere with a front-mounted 785 cc, single-cylinder engine, a shaft and bevel-driven rear axle, and a three-speed

steering column gear change.

The model was intended for mass-production, and, although demand never reached the heady heights dreamed of by Darracq, it did sell by the hundred, and was also built under licence in Germany by Ope!. By 1903, the range had grown to four cars: a 1.1-Iitre single, 1.3 and 1.9-Iitre twins and a 3.8-litre four. The following year, all the multi-cylinder models had acquired pressed-steel frames instead of the flitch-plated wood chassis of the earlier model. There was also a new 'Flying Fifteen' 3-litre four, whose frame, pressed from a single sheet of steel, was a masterpiece of metal forming.

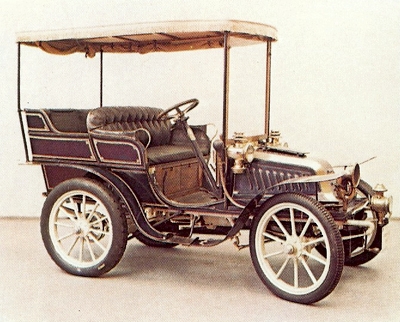

This Darracq used a single-cylinder 1281cc engine producing 9 bhp at 1200 rpm.

This Darracq used a single-cylinder 1281cc engine producing 9 bhp at 1200 rpm.

1902 Darracq single-cylinder.

1902 Darracq single-cylinder.

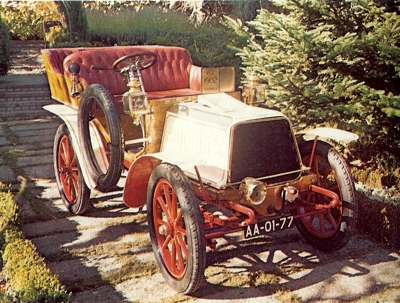

1908 8/10hp Darracq, which was fitted with an 1100cc single cylinder engine.

1908 8/10hp Darracq, which was fitted with an 1100cc single cylinder engine.

1912 Darracq, which featured a four-cylinder Henriod rotary-valve engine.

1912 Darracq, which featured a four-cylinder Henriod rotary-valve engine. |

During this period, the marque's name was being kept in the sporting public's eye by a series of extravagantly-lightened racing

voitures legeres while, in 1904, Alexandre Darracq, who was renowned for the fact that he never missed a trick, tried to win the Gordon Bennett Trophy by sheer brute force, entering teams of identical cars built in Britain, France and Germany. However, the 11.3-litre monsters failed miserably. Far more successful was the 1905 200 hp V8 sprint car, which used two Gordon Bennett-type cylinder blocks with overhead valve gear on a common crankcase; it was capable of virtually 120 mph and was one of the two fastest cars in the world.

Alexandre Darracq's enthusiasm for motor sport was all the more remarkable because, though he was said to have taken driving lessons in July 1896, he apparently hated riding in cars. The marque's great racing days ended in 1906 with Louis Wagner's second victory in the American Vanderbilt Cup, driving a 12.7-litre racer. After that, all was anti-climax, and Wagner joined the Fiat team in 1907. One final rac.e, the 1908 'Four-Inch' Isle of Man Tourist Trophy, in which the team took second, third and seventh places, closed the record as far as the factory was concerned, though

Malcolm Campbell raced ex-works Darracqs at Brooklands in 1912.

Sending Fordyce to America To Secure Wright Brothers' Patents

In any case, Darracq had found a new enthusiasm - or, at least, a new source of profits - in the infant sport of aviation, sending a journalist named Fordyce to America in 1907 to bargain for the Wright Brothers' patents. A couple of years later, the Suresnes factory began production of a light aero-engine which was used by such intrepid birdmen as Bleriot and Santos-Dumont. For the time being, the company's aeronautical activities remained a sideline, though they assumed a more serious aspect during World War 1.

Another peripheral activity proved more costly for, in 1906, Darracq signed an agreement with Serpollet, planning to flood the capitals of Europe with fleets of steam buses. The flood was never more than a trickle, with only a few dozen buses ever going into service - 20 ran in London - and the company suffered a loss. A further disaster had a major impact on motoring history. In 1906, a factory had been set up in Milan to build Darracqs for the Italian market, but the cars failed to sell in sufficient numbers and, by 1910, the Societa Italiana Automobili Darracq was out of business. In its place came the Anonima Lombardo Fabbrica Automobili; ALFA was taken over by Nicola Romeo in 1914, and Alfa Romeo was born.

By 1911, it looked as though Alexandre Darracq· was back on course again. He had proposed, as early as 1898, to build cars that combined quality and low cost, by making use of the economies that could be achieved by series production. True, he had just killed off the last of the old, ultra-cheap, single- cylinder models, and the twins had only a few months to run, but a new 14-16 hp model costing only £260 in Britain seemed to augur well for the marque's future. However, Alexandre Darracq was about to invoke his personal Nemesis again. After much unaccountable juggling with the range, he announced, in 1912, that most of the line-up would be graced with the Henriod rotary-valve. engine, which featured a single port for each cylinder performing as inlet or

exhaust depending on the position of the rotating valve shaft.

The Rotary Valve Darracq

Early rotary-valve Darracqs had a dashboard

radiator a la Renault, but a redesign of the valve gear permitted the use of a conventional cooler. The Henriod-powered models ranged from 2.1 to 3.6 litres and all were completely gutless, as well as being liable to seize up. Profits-and the marque's reputation-plummeted, and Alexandre Darracq resigned. He died in 1931. The firm was placed under the control of a Yorkshireman, Owen Clegg, who had designed the very successful Rover Twelve. Not being one to change a winning formula in the face of a crisis, Clegg based the new Darracq on the Rover; the Henriod was immediately chopped, andthe Suresnes works completely re- equipped for mass-production.

The 16 hp Clegg- Darracq had an engine of just under 3 litres, and was soon joined by a 2. r-Iitre, 12 hp model; both were handsomeswell-proportioned, reliable cars and, within months, production had risen to 60 cars a week. By the autumn of 1914, 12,000 men were working at Suresnes, turning out 14 chassis daily. The 16 hp, anglicised still further, was the leading post-Armistice model, but was soon joined by a 4.6-litre V8 with four forward speeds and-from the end of 1920-four-wheel braking as well.

For all its advanced specification, the new car proved a disappointment, and was gently phased out over the next three or four years. By that time also, A. Darracq & Co Ltd (the company had been re-registered in England in 1903 to dodge French fiscal law) had ceased to exist. In October 1919, they had acquired Clement-Talbot of London, only to be themselves swallowed up by Sunbeam. Though the Darracq name survived on those of the Sunbeam-Talbot-Darracq group's products destined for Britain or its Empire, it was no more than a very convoluted exercise in badge-engineering, and the latter history of the cars from Suresnes form part of the

Sunbeam and Talbot stories.