FOR OVER THREE DECADES, DKW was a leading name in the development of the small, efficient saloon car, pioneering mass production of both front-wheel drive and the two-stroke car engine. Not for nothing did the marque's adherents nickname it 'Das Kleine Wunder' - the little wonder - although the initials really stood for Deutsche Kraftfarzeug Werke.

DKW began life as a motor-cycle manufacturer in the early twenties but, in 1928, it was decided to enter car manufacturing, even though the motor-cycle business was flourishing. The DKW was built at the Zschopauer Motoren Werke in Berlin at the factory previously occupied by the Deutsche Werke AG, makers of the D-Wagen car.

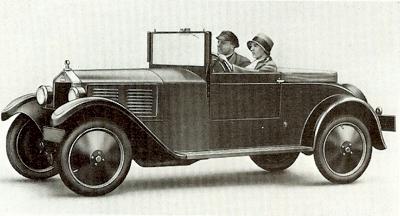

The owner of the DKW factory, Jorgen Rasmussen, decided that he would power his first car with a two-stroke engine of the type which had been so successful in his motor cycles. The engine that he chose was a vertical twin-cylinder unit with dimensions of 68 x 74 mm, giving a capacity of 584 cc and a power output of 16½ bhp. This was relatively modest even for 1928, but Germany was in the midst of a cycle car boom, occasioned by the onset of the Depression years.

Despite the tiny engine, Rasmussen designed quite a sophisticated car around it, using an advanced

unitary construction body/chassis largely made from wood. The car had a proven gearbox and even a differential, items which many cyclecar manufacturers deemed unnecessary.

The result was that the little DKW became quite popular among the less well off, and many examples of the first DKW car were still in daily use well into the fifties. DKW did not neglect the sporting market and, for 1930, they introduced a pretty sports car along the same lines. The engine was given different port timing and a higher compression ratio of 5.5:1 to raise the power output to 18 bhp.

The tiny boat-tailed sports body with separate wings was an instant hit with young drivers and, with an all-up weight of around 10 cwt, it was capable of topping 60 mph-quite a feat for such a small car in 1930. With transverse leaf springs front and rear, it handled as well as most other small sports cars.

The two-stroke DKW engine was beginning to impress many people, for the water-cooled, reverse- scavenged unit was much smoother and easier revving than previous attempts at making two-stroke engines had been, and Rasmussen was encouraged to expand his range upwards. His first effort to this end was to enlarge the engine to 780 cc for the 4/8 saloon of 1930; in this form, the engine gave 22 bhp, a very good. specific output for a small car of this period.

In 1931, the first front-wheel drive DKW appeared. This was the F1, a technically advanced little car which set a high standard for manufacturers of small saloons over the next decade. For the F1, the stroke was reduced from 74 mm to 68 mm to give a capacity of 490 cc and a power output of 15 bhp at 3200 rpm. The twin-cylinder engine was mounted across the frame, and drive was taken to the front wheels via a three-speed gearbox and a multi-plate oil-filled clutch. DKW were to stay faithful to this layout for most of their subsequent models, and it remained virtually uncopied until Citroen and BMC brought out their transverse-engined,

front wheel drive cars in the fifties.

The first DKW was the 584cc two-stroke of 1928.

The first DKW was the 584cc two-stroke of 1928.

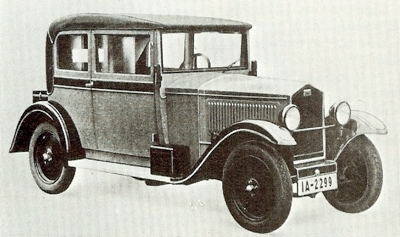

In 1930, DKW produced the P25.

In 1930, DKW produced the P25.

1931 DKW F1 Model , which was powered by a tiny 490cc twin-cylinder two-stroke mounted across the frame.

1931 DKW F1 Model , which was powered by a tiny 490cc twin-cylinder two-stroke mounted across the frame.

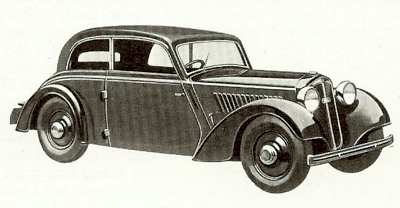

1938 DKW Sonderklasse 32PS, which featured a 1050cc four cylinder engine driving the front wheels.

1938 DKW Sonderklasse 32PS, which featured a 1050cc four cylinder engine driving the front wheels.

The DKW F1 was developed to become the Meisterklasse. This range retained the vertical twin-cylinder two-stroke layout, but the motor was enlarged to 684cc.

The DKW F1 was developed to become the Meisterklasse. This range retained the vertical twin-cylinder two-stroke layout, but the motor was enlarged to 684cc.

1939 Auto Union DKW F9 Prototype.

1939 Auto Union DKW F9 Prototype.

1950 DKW Auto Union 1000 Van Pickup.

1950 DKW Auto Union 1000 Van Pickup.

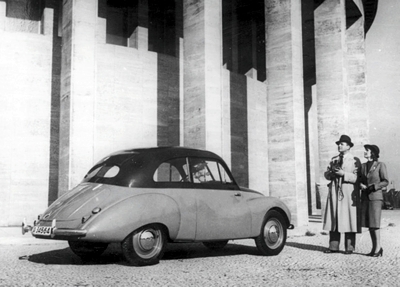

1951 DKW F89 Meisterklasse.

1951 DKW F89 Meisterklasse.

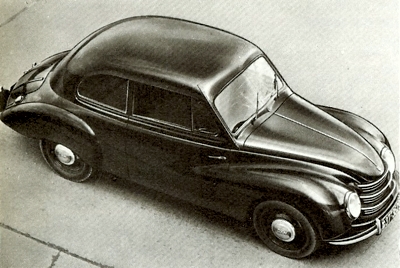

1953 896cc Sonderklasse.

1953 896cc Sonderklasse.

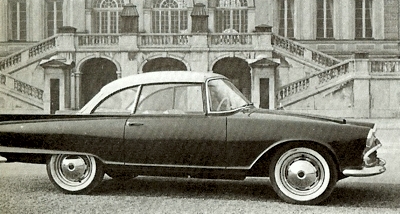

DKW Auto Union 1000 Coupe.

DKW Auto Union 1000 Coupe.

DKW F102.

DKW F102. |

The F1 had a ladder-type steel frame with independent front suspension by swing axles, and a dead axle on transverse leaf springs at the rear. The body was now made from steel but, even so, the two-seater F1 weighed little more than 10 cwt and was good for 50 mph. An almost identical car, the F2, was built alongside the F1, the only major difference being the engine, which was the original 584 cc unit, still giving 18 bhp at 3200 rpm.

Rasmussen's determination to stick with small cars paid off for, in the Depression years, he was able to survive and even expand. By 1928 he had become the majority shareholder in Audi, the company started by August Horch, and, in 1932, he gathered into his fold both Horch and Wanderer factories. The four companies in the group, Horch, Audi, Wanderer and DKW, were grouped under one name - Auto Union - and the company badge was designed to show four inter-linked rings.

The new company was rivalled in size and prestige only by the Mercedes-Benz group. Rasmussen was presented with a bewildering selection of cars, ranging from his own tiny DKWs, through the medium sized Wanderer range, to the larger Audi and even bigger 5-litre straight-8 Horch. The DKW and Horch cars were allowed to continue on their own lines, but both Wanderer and Audi were intermingled to a large extent over the ensuing years and, by the outbreak of World War 2, both makes were being produced only in small numbers.

The Wanderer Puppchen

Wanderer began car production in 1911 with a small, two-seater, 1500cc car, popularly known as the Puppchen (doll), and from then on they made workmanlike but un- exceptional cars until the merger in 1932. They had, however, built most of their engines with overhead valves at a time when the side valve was almost universal on cheaper cars. Audi had a rather more distinguished history, largely because they tended to build bigger, more sporting cars.

After being forced to sell his own company in 1906, due largely to his preoccupation with engineering at the expense of finance, August Horch started up again in 1909 just down the road from his old factory in Zwickau. He called the firm Audi, which is the Latin for Horch. His first car under the new name was the B10/28, powered by a 2.6-litre engine; this was followed by the C14/35 'Alpensieger', with a four-cylinder, 3.5-litre engine giving 35 bhp at 1700 rpm.

The standard model was capable of 55 mph, but Horch, who was fond of taking part in the strenuous Alpine Trial, built a lightweight car with a much shorter wheelbase than the 10 ft of the standard tourer, and fitted it with an aluminium body. This car was particularly successful, winning the Alpine Trials of 1912, 1913 and 1914, hence the name of Alpensieger-Alpine winner.

The company also catalogued two larger-engined cars in the years leading up to the war; one, the D18/45 had a 4.6-litre engine and the other, the E22/50, had a 5.6-litre unit. After World War 1, the pre-war range was again put into production but a new car, the model K, was soon announced. This had a 3½-litre, four-cylinder engine mounted in unit, not only with the gearbox, but with the

radiator and

steering box as well. The engine gave about 50 bhp and moved the car along at 60 mph.

The K was the forerunner of perhaps the best Audi built up to that time; this was the M18/70 which first appeared in 1923. It was powered by a 4.6-litre, overhead-camshaft, six-cylinder engine which had a block cast in silicon aluminium, duralumin connecting rods, steel cylinder-liners and a seven-bearing crank-shaft. It was a smooth unit which gave 70 bhp at a modest 3000 rpm and was capable of shifting the big car along at 75 mph, It was able to hold its own with many of the best German cars of the time and was in steady demand despite its high price.

However, the fortunes of Audi began to decline gradually. Horch himself, although still a board member, no longer had anything to do with design; and the firm went deeper into trouble when they introduced an 8-cylinder car in 1928. This car, the R type or Imperator, had a straight-eight, 4.8-litre engine giving 100 bhp.

It made use of several light metals but was a prosaic side-valve unit. Even the chassis layout was ordinary, with leaf springs on the rigid axles front and rear, although the rear axle case was made from silicon aluminium. It was a big, heavy chassis on which some attractive bodies were fitted and, although it was capable of cruising at 75 mph, there was a declining demand for prestige cars.

American Rickenbacker

Rasmussen made an offer for Audi in 1928, which the directors accepted, and he became the controlling shareholder. His first aim was to build cheaper cars, so he reached agreement with the American Rickenbacker company to build their engines under licence. Six and eight-cylinder engines were built by Audi, but the Rickenbacker engines were rather dull side-valve 3.8 and 5-litre engines which had neither great power nor sophistication. These units were fitted to the Zwickau and Dresden models while the Imperator carried on in production until 1932, the year of the merger.

Audi's individuality gradually disappeared after the merger until the factory was really an assembly area for parts supplied by others in the group; in fact, the firm was obliged to move to the Horch works so there was little left of the old Audi company after 1932. Rasmussen introduced a cheaper Audi in 1931, using a Peugeot 4-cylinder 1100 cc engine in a DKW chassis. This never got into full production so, in 1932, Audi introduced a new model, the 225, which featured an enlarged DKW

front wheel drive chassis into which had been fitted a Wanderer 2.3-litre, six-cylinder engine, the chassis being clothed in a body designed at the Horch factory.

The engine was interesting as it had been designed, before the merger, by Ferdinand Porsche; it was a light ohv six using an alloy block, cast-iron

cylinder head, wet liners and a seven-bearing crankshaft. Wanderer never developed the engine to give very much power, and it had only a relatively feeble 40 bhp at 3500 rpm. The car suffered various teething troubles connected with the gearbox and steering, and it never sold in any quantity.

DKW Remains The Best Selling Car In The Auto Union Group

DKW remained the best selling car in the Auto Union group during the thirties largely because the company remained faithful to small cars. The F1 model was developed into the Reichsklasse, with a 584 cc engine, and the Meisterklasse of 684 cc, still retaining the vertical-twin, two-stroke layout and front-wheel drive. The cars had become larger, with a wheelbase of over 8 feet, but this allowed the use of a full four-seater body, which had returned to the wood and fabric construction of the early models.

Sonderklasse and Schwebeklasse

DKW also produced a range of conventional cars alongside the

front wheel drive models. These cars, known as the Sonderklasse and Schwebeklasse, used a V4 engine at the front, driving the rear axle, but the inherent roughness of the V4 coupled with the relatively modest power output of 26 bhp from the 1054cc engine caused sales to proceed at a dribble compared with the booming sales of the

front wheel drive cars. Exports of the small cars built up well in the thirties and, in England, they established a small but expanding foothold in the market.

Auto Union became heavily involved in motor racing in the early thirties with the V16 car, but most of the work was carried out at the Horch factory to Porsche designs and, as the Nazi Government was subsidising the racing programme, it had little effect on the production programme, neither influencing design nor affecting adversely the company's financial situation. The twin-cylinder DKWs continued in production right up to the outbreak of war in 1939, differing only in minor details apart from the increasing sumptuousness of the bodies which were becoming heavier all the time.

As well as four-door saloons there was a handsome cabriolet with wire wheels. In 1938, Audi, who had persevered with the dull Rickenbacker-engined cars, introduced the 920, a much more ambitious car. Using a box-section chassis with independent front suspension by wishbones and transverse-leaf springs, and a rigid rear axle with transverse-leaf springs, the car was powered by a six-cylinder engine which was evolved simply by removing two cylinders from the Horch straight-8. With dimensions of 87 x 92 mm and a capacity of 3281 cc, this single-overhead-camshaft engine produced 82 bhp at 3600 rpm which was good enough to propel the big saloon and cabriolet bodies at 85 mph with ease.

Having a good

synchromesh four-speed gearbox with over-drive, and sumptuous bodies, Audi were once again in a position to challenge the prestige cars of Germany, but production was sadly curtailed by the onset of war. From 1939 to 1944, the Auto Union factories settled down to war production, largely aeroplane engines and parts, but DKW did continue car production until 1941; they even had a brand new three-cylinder, two-stroke-engined car ready for production in 1940 but it was abandoned.

DKW Occupied by the Russians

At the end of the war, the Auto Union factories were occupied by the Russians, and later the East German authorities nationalised them. Car production gradually started up again but, as the Auto Union company had the rights to use the names Horch, Audi, DKW and Wanderer, the East Germans called their DKW, derivative the Trabant, while the new 'Horch' was known as the Sachsenring. In Poland, a copy of the pre-war two-cylinder DKW was known as the Syrena, while an East German company, Wartburg, also built cars to DKW designs.

The names of Horch and Wanderer died at the outbreak of the war but a new Auto Union company was formed in 1949 to produce the DKW again. The factory was situated in Dusseldorf, and initial production was centred on an updated version of the Meisterklasse, with a two-cylinder engine and a modern body. Once the factory was established and had begun supplying car-starved Europe, they resurrected the 3-cylinder design of 1940. This engine, with bore and stroke of 71 x 76 mm had a capacity of 896 cc and developed 34 bhp at 4000 rpm on a com- pression ratio of 6.5:1. It was mated to a four-speed gearbox with

synchromesh on the top three; top speed for the standard saloon was in the region of 75 mph.

Suspension followed pre-war practice, with wishbones and transverse-leaf springs at the front and a dead axle with transverse leaf springs at the rear. This new Sonderklasse model caught on well with the public, and it was soon being produced as both a two and four-seater drop-head coupe and a station wagon, as well as the normal four-seater saloon. A new model with the engine increased in size to 981 cc and a power output of 40 bhp was marketed under the Auto Union name and was known as the Auto Union 1000.

The more sporting versions were also known as Auto Unions, largely to cash-in on the marque's pre-war reputation. The most popular models were the 100 SP Coupe and Convertible which had attractive modern bodies; both cars were capable of exceeding 90 mph and they established a keen following of discerning buyers over the years. The bulbous-bodied Sonderklasse was superseded by the Junior, which had a more modern body as well as torsion bar front and rear suspension. This two-door saloon was good for 75 mph and had the option of the Saxomat automatic clutch.

The Junior was followed by the F11, F12 and F102 saloons, each having improvements over the earlier models mainly in the interior accommodation and styling, but all the cars retained the basic mechanical components of the Sonderklasse. In 1956, Mercedes-Benz had gained a majority shareholding in Auto Union, but they made no great attempt to interfere with the design of the cars, leaving the company to go its own way.

Dieter Mantzel and Gerhard Mitter

The competition potential of the two-stroke DKW engine was realised in the late fifties when a Heidelberg engineer, Fritz Wenk, built a glassfibre-bodied car called the Monza which used a tuned engine in a near-standard DKW chassis. This sold quite well in Germany and won a few competition events as well as taking a number of class speed records at the Monza track in Italy, from where it gained its name. The German tuners, Dieter Mantzel and Gerhard Mitter, began to extract phenomenal power outputs from the DKW 'three', and they started to win hill-climbs and other short distance events, but the engines tended to overheat when held at peak-revs in circuit races.

Mitter designed a sports version of the engine using four upright cylinders for which he claimed 130 bhp, but it seldom held together for very long. He also used a three-cylinder engine in Formula Junior racing as did Britain's Elva but, although the engine showed promise, the centre

piston always overheated. By the early sixties, enthusiasm for the two-stroke was beginning to wane despite the success of Saab, who had used a two-stroke engine similar to the DKW with great success in competition. Sales gradually began to decline in the face of the more sophisticated four-stroke engines now on the market.

Volkswagen Takes A Controlling Interest

Volkswagen had taken away the company's volume sales and, in 1964, Volkswagen acquired a controlling interest. Sales of the two-stroke cars continued into 1966 and, in 1965, the name of Audi was resurrected for a new front- wheel-drive car, the Audi 80. This used the body and most of the suspension components of the DKW FI02, but the two-stroke engine was replaced by a 1.7-litre four-cylinder unit giving 80 bhp at 5000 rpm. The car was immediately successful and subsequently the stylish 50, 90 and 100 series have proved equally popular. Volkswagen took control of the NSU factory and merged it with Audi, and the company began producing some advanced ideas from their engineering department.

The Wankel-engined NSU R080 was one result, and the five-cylinder models introduced in 1976 were another. In 1972 Volkswagen were obliged to use two front-wheel drive Audi designs, the new 50 and 80 models, to bolster flagging sales of the Beetle. The Audi 80 was also sold under the VW name as the Passat, and the 50 as the Polo. Although the DKW name would never again be used on a car, some of the principles laid down by Rasmussen many years ago, were adhered to in the Audi range through the late 1970's.