Duryea

|

1891

- 1917 |

Country: |

|

|

WHO BUILT AMERICA'S FIRST CAR? If the number of times Unique Cars and Parts are asked this question is anything to go by, then it has obviously been the subject of controversy almost as long as motor vehicles have existed in the United States, and the number of claimants is legion: Plass, Haynes, Schloemer, Ford, Lambert, King and so on.

One thing is for certain however: the first company set up in America to manufacture cars for sale to the public was organised by the Duryea brothers, Charles and Frank. Though the precise details were clouded in later years by Charles's mendaciousness, which led to a quarrel between the two, it seems that Charles was the dreamer and Frank the doer; Charles had the ideas and Frank had to make them work.

Charles, the elder brother, was born in 1861, the son of a farmer in Canton, Illinois; Frank was eight years younger. From an early age, Charles was intrigued by the concept of self-propelled transportation; he built a high-wheel bicycle, using a 42 in wheel from a corn cultivator, a tiny rear wheel from a toy cart and a curved sapling for a frame.

A Flying Machine Will One Day Cross The Atlantic

In 1882 Charles Duryea graduated from the Giddings Seminary at LeHarpe, Illinois, writing a thesis on 'Rapid Transit', in which he prophesied that a flying machine would eventually be able to cross the Atlantic in half a day. He moved to St Louis, where he entered the cycle trade; he seems to have been a natural wanderer, for he had soon transferred operations to Peoria, Illinois, where, in partnership with a man named Rouse, he built the Sylph, one of the earliest drop-frame ladies' bicycles.

From Peoria, Charles went on to Washington DC, then to Rockaway, New Jersey, where Frank, who had just left high school, joined him. During these peregrinations, Charles had visited the 1886 Ohio State Fair, where a mechanic from Dayton (home town of the Wright Brothers), H. K. Shanck, exhibited a crude

internal-combustion engine that he hoped to adapt to drive a tricycle.

Duryea became obsessed with the idea of building a gasoline motor wagon and, late in 1891, he visited Frank (by now working as a toolmaker at the Ames Manufacturing Company, of Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts), and told him that he had found the ideal engine and transmission for the proposed motor vehicle. This is a debatable point, as the engine was an untried design by C. E. Hawley, of the Pope cycle company of Hartford, Connecticut, which had a 'free piston' fitting over the normal

piston to open and close the

exhaust valve, while the friction transmission was of dubious practicality.

Duryea Partners With Erwin F. Markham

Nevertheless, Charles began to look for a backer to finance the building of a car, and a fortuitous meeting in a tobacconist's shop with a businessman named Erwin F. Markham led to Markham offering to advance $1000 towards the cost of a car, in return for a 10 percent interest in the machine (which would rise to 50 per cent if the backing continued until the car was a success). Frank agreed to build the car, found a workshop and bought a second-hand phaeton which he planned to adapt to take the engine and transmission. He began work in April 1892, and continued right through the summer.

Meanwhile Charles, smitten with the old wanderlust, had gone back to Peoria and the Rouse-Duryea Cycle Company, leaving Frank to struggle with the unfinished car. Illness held up the work until January 1893, by which time Markham was understandably demanding to see some progress and threatening to withdraw his backing. Having managed to complete the free-piston engine to Hawley's vague design, Frank now found that it would not run. As a desperation measure, he pinned the pistons together, and made the engine perform well enough for him to extract some more money out of Markham, though it was too clumsy and feeble to fit in the carriage.

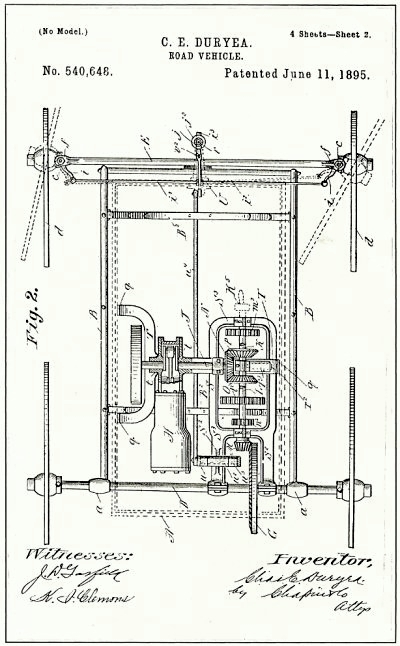

A page of the first patent taken out by Charles Duryea. This is dated 11 June 1895. In the bottom right-hand corner of the picture can be seen the signature of Charles Duryea himself. It was this patent that caused great friction between the two Duryea brothers, as the original design had been the work of Frank Duryea and not Charles No. 540,648.

A page of the first patent taken out by Charles Duryea. This is dated 11 June 1895. In the bottom right-hand corner of the picture can be seen the signature of Charles Duryea himself. It was this patent that caused great friction between the two Duryea brothers, as the original design had been the work of Frank Duryea and not Charles No. 540,648.

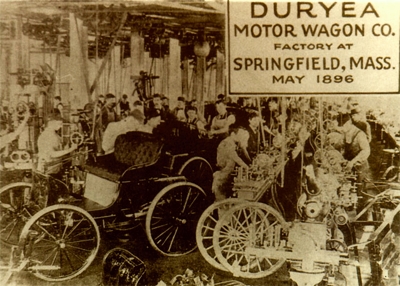

The Duryea Moror Wagon Company.

The Duryea Moror Wagon Company.

The Duryea Moror Wagon Company.

The Duryea Moror Wagon Company.

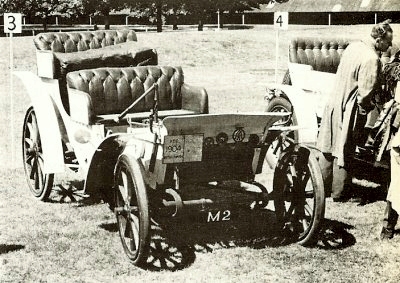

A 1904 Duryea produced by the British Duryea company, which was established in 1901. The operation was headed by Henry Sturmey.

A 1904 Duryea produced by the British Duryea company, which was established in 1901. The operation was headed by Henry Sturmey. |

Duryea then designed and built an entirely new power unit and, by September, the car was ready for the road.

The first public trial took place on 22 September 1893;

'But,' recalled Frank in 1948, '

because of its friction transmission, the car was barely operative, and I was never able to give a demonstration to a possible investor'. Once again, Markham threatened to withdraw, but Frank managed to persuade him to provide enough cash to pay for the construction of a proper friction clutch and three-speed gearing (but had to forego a salary); in January 1894, the car made its first successful run, Markham, however, had run out of spare cash - and patience.

In March 1894, Frank, after six weeks without salary, found a new backer and began work on a second car. To keep his brother informed, Frank mailed a set of drawings of the new car to Peoria and Charles promptly patented them in his own name, sparking off a dispute that would outlive them both.

Frank, now out on his own, demonstrated the second car throughout the summer and, in September 1895, set up the Duryea Motor Wagon Company at Springfield, Illinois. Two months later, he won the first American motor race, organised by the Chicago Times-Herald; 80 cars were entered, only six turned up at the start, and only the Duryea and a Benz finished.

For some reason, Frank Duryea was so taken with the design of the Benz that he based his next model on it; 13 of these were built for sale during 1896, and two of them were shipped to Britain to take part in the London-Brighton Emancipation Day Run that November, where they impressed

The Autocar with their performance: '

The Duryea made but little noise, and was going great guns; indeed, its pace, as it ran off the grade on to the level, could not have been less than twenty miles per hour'.

As the Duryea had not been built by one of motor mogul Harry J. Lawson's companies, there were subsequent attempts to denigrate its showing - claims that it had not actually been driven to Brighton, but had been taken down by train and then splashed with mud - but the facts that the car was involved in a traffic accident at Crawley, where it knocked down a little girl named Dyer, and that its passenger, coach- builder G. H. Thrupp, of Thrupp & Maberley, testified on oath that he had travelled all the way to Brighton, bear out its claim to first place in the heavy car section of the run.

Frank Duryea even set up an import agency near Cannon Street in the City of London, headed by one J. L. McKim. However, the motor car was still too much of a novelty to be a commercial success - one of the first 13 Duryeas was loaned to Barnum & Bailey's Circus as an added attraction among the clowns, freaks and performing animals of the Greatest Show on Earth - and in 1898 the Duryea Motor Wagon Company folded.

Frank tried to carry on alone, built one car, and then joined the Stevens Arms & Tool Company, of Chicopee as Vice-President and Chief Engineer in 1901; he designed the Stevens-Duryea car, which was an immediate success (50 were sold in the first season of production) and became one of America's top quality cars of the Edwardian era.

Frank sold out in 1915, when the firm was at the peak of its success. He travelled extensively and, though beset by periodic bouts of ill-health, survived to the age of 97, dying on 15 February 1967. Charles Duryea picked up the pieces of the Motor Wagon Company, which was reformed in 1898 as the Duryea Power Company, of Waterloo, Iowa, though production did not seem to get under way properly for a couple of years, except for a number of three-wheelers with rear engines. Four-wheelers were added to the range around 1900.

Initially, these had flat-twin engines, but soon the characteristic power unit of these second-generation Duryeas was evolved. It was a splash-lubricated, 10 hp, transverse three-cylinder engine, probably the first to employ an offset, crankshaft, which gave a direct thrust on the driving stroke.

Carriages, Not Machines

These cars featured a perfected version of the 'one-hand control' essayed in primitive form on the 1893 car; moving a lever between the seats from side to side steered the car, pulling it back shifted the two-speed epicyclic gear into low speed, twisting the grip opened the throttle, and pushing the lever down engaged neutral. Duryea claimed '

The whole control of the car is effected almost by a thought'. In fact, the

steering probably was the most scientifically laid out of the period. 'Carriages, not machines', was the slogan under which these cars were marketed, and the shell-shaped coachwork had a baroque charm all its own.

The Duryea was like no other veteran car, each of which Charles Duryea dismissed as 'a cross between a locomotive and a fire engine'. In 1901, a British Duryea Company was organised at Coventry, initially as a sales agency for the American-built cars. In 1904, though, production of British- built Duryeas began, using parts manufactured by Willans & Robinson of Rugby. The operation was headed by Henry Sturrney, founder-editor of

The Autocar, but survived only until 1907.

The American company, which moved to Reading, Pennsylvania in 1903, had persisted with the original Power Carriages during this period, but now went off at a tangent, producing a crude, solid-tyred high-wheeler for 1908, under the name Buggyaut. The twin- cylinder engine drove the rear wheels by friction and, in most respects, the car was inferior to the 1895 model. However, it lasted until 1913 at least, and a curious sports version was illustrated in the

Light Car as late as 1916.

By this time, Charles Duryea had returned to the three-wheeler theme with the Duryea Gem, a torpedo like cyclecar with Buggyaut engine and transmission. It lasted for only a very short period from 1916 until 1917. '

Follow me and you will have diamonds', Charles Duryea had once said to Frank. But there is no difference in chemical composition between diamonds and charcoal, and all Charles's projects seemed to end in ashes.

Charles Duryea died in 1938, aged 76, convinced in his own mind that he had built and operated America's first car in 1891, two years before brother Frank had actually made his first faltering run down Spruce Street, Springfield.