Grice, Wood and Keiller

Grice, Wood and Keiller were responsible for manufacturing one of the most successful friction-driven cars in motoring history: the GWK, whose proud boast was' 'a gear for every gradient'. The prototype was made at the Home Works, Datchet, a Thames-side village in Buckinghamshire, UK; it used a Coventry-Simplex engine, rear-mounted. Its friction-drive transmission was inspired by the mechanism of an optical grinding machine. The drive system involved the engine, which was mounted across the chassis, turning a disc on which a wheel could be moved from the periphery to the centre.

Top speed was with the driven wheel furthest from the centre and reverse was obtained by moving it past the centre. A few examples were sold before the company moved to Datchet, Buckinghamshire in 1912. Proper production started, the company still using a water-cooled, Coventry-Simplex twin-cylinder engine of 1045cc and 1069 two-seat cars were made before the outbreak of World War 1 and a move to war work. A move was also made to the larger Cordwallis Works in Maidenhead in 1914.

How did the GWK Transmission Work?

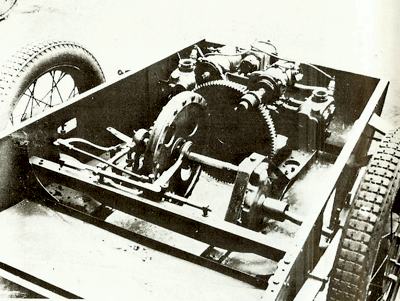

1920s motoring expert Oscar E. Seyd described the GWK transmisson ... 'The outstanding feature of the chassis is, of course, the special GWK friction drive, or disc drive, as is actually the more correct designation. This takes the place of the gearbox found on cars of orthodox design. The system consists of two discs. One of these is driven by the engine and imparts power to the road wheels, driving by contact the other disc which is attached to the live axles.

One may conceive the idea by imagining two coins. One has a hole at its centre, and the other is set at right angles to it so that the periphery of the latter bears on the face of the other. If the disc with the hole in it is rotated, the friction between the two will cause the other to be turned also, and the ratio between the speed of the first and that of the latter will depend on the distance of the latter from the centre of the first.

If the driven disc be at the extreme edge of the driving disc, their two speeds are practically the same, and the nearer the driven disc approaches to the centre of the other, the slower its speed. If the driven disc passes across the centre of the driving disc on to the other side, its direction of rotation is reversed. As the driving disc has a hole in its centre, when the driven disc is opposite this hole, it is obviously not turned at all.' So went the explanation. Just in case there were some left still scratching their heads, Mr Seyd hastened to clarify: 'Although this explanation may appear a little involved, a moment's reflection with the two coins will make the principle quite clear to those to whom it is new'.

Coventry Simplex

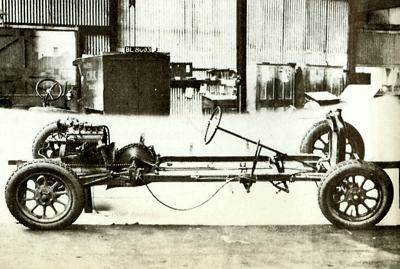

The first GWK had a rear-mounted Coventry Simplex vertical-twin-cylinder engine set transversely across the chassis immediately behind the driver's seat; the swept volume was 1096cc, which gave a lively performance, for the top speed was around 55 mph. The chassis, unusually for such a low-priced (almost) cyclecar, cost only UK£150, fully equipped. The chassis was a proper pressed-steel unit, with semi-elliptic springs in front. Rear

suspension was by means of

quarter-elliptic springs.

The car's mettle was proved by numerous successes in the light-car trials of the day, and demand from the 'New Motorists' who were prepared to exchange the stormy clangour of a mishandled crash gearbox for the silent change of the GWK (and the minor inconvenience of having to replace the compressed-paper friction band when, inevitably, over-enthusiastic ratio changing wore a 'flat' on it which resulted in a rhythmic thumping as the car travelled along) was such that over 1000 GWKs were delivered between the start of production in 1911 and the firm's changeover to wartime Admiralty munitions contracts shortly after the beginning of World War 1. During the war the company was run by Grice as his partners were in the army.

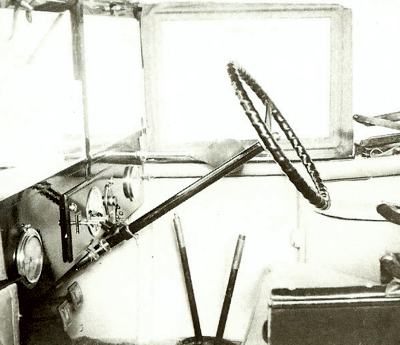

1923 GWK 10.8 interior.

1923 GWK 10.8 interior.

1923 GWK engine and transmission setup.

1923 GWK engine and transmission setup.

1923 GWK engine and transmission setup.

1923 GWK engine and transmission setup. |

After the war, GWK moved into a new factory, the Cordwalles Works at Maidenhead, and in 1919 began to produce a new model with a four-cylinder, 10.8 hp Coventry Climax engine at the front, under a bonnet of conventional appearance. Incidentally, in view of the company's long association with Coventry Simplex and its successor, Coventry Climax (they were the first manufacturers to fit this make of power unit), it is interesting to note that Leonard P. Lee, son of the founder of Coventry Simplex, served his apprenticeship with GWK.

The GWK Type E and Type F

Grice left the company in 1920 to start the unsuccessful Unit car company leaving Wood and Keiller in charge. Grice produced a completely unsuccessful neo-GWK, the Unit which went through several iterations before vanishing into limbo in 1924. Back at GWK, the company re-introduced the pre-war model, now called the Type E, and a further 82 were made largely from left over parts. A new model, the Type F was introduced in 1919 and was front-engined with a 1368 cc four-cylinder engine, still by Coventry-Simplex, with shaft drive to the friction disc at the rear. It was not a good seller partly because of the noise from the transmission. The Type H overcame most of the drive line problems but suffered from the reputation of its predecessor. About 1700 of the Types F and H were made between 1919 and 1926.

There was one problem with the post-war GWK, which had to do with the cork friction lining, which tended to wear more quickly than the earlier compressed-paper material; the extra weight which the car had put on in its transformation did not help matters, as it blunted the edge of the vehicle's performance. 'Under normal touring conditions it will run all day at thirty miles an hour, while well over forty may be obtained when a top-speed burst is required', commented a 1922 road test. Petrol consumption of the new model was notably inferior, too, at 30 mpg compared with the twin's 45 mpg. This may well have been due to transmission slip, as the same power unit was fitted to Clyno cars, which claimed a much more economical 40 mpg.

Indeed, the 10.8 hp GWK had an 'extra-pressure' pedal to increase the friction between the discs when slip occurred on steep hills, especially when attempting to reverse up the slope. From the new model's inception, two and four seater tourers were available, and a coupe was added to the range in 1922. Prices were extremely moderate, the two-seater costing UK£285, the four-seater UK£295 and the coupe de luxe UK£360. The makers claimed that the four-seater was the cheapest water-cooled car, of this passenger capacity, on the British market, conveniently ignoring the

Model T Ford.

'These figures,' stated the 1922 tester, 'represent remarkably good value, for they will purchase a thoroughly sound, reliable, economical touring light car of proved excellence, equipped with dynamo lighting and the usual refinements which all but the most fastidious owner-driver demands'. Whatever those fastidious owner-drivers did demand, it seems that the 10.8 hp GWK was not among them, for sales fell, and attempts to reverse the trend by assembling 'new' rear-engined cars using pre-war components did not help. From 1923 the GWK was fitted with four-wheel-braking, an early use of all-round stoppers on a car of this size and price, but even this addition to the specification failed to attract customers. The same year, the 11.9 hp Coventry Climax engine became available, but it added more to the weight than to the performance, so it was not a worthwhile modification or alternative.

The company had not given up on the rear-engined idea and a new car, the Type J, appeared in 1922 but only a few were sold. It had a bonnet and radiator very similar to the front-engined cars. The final car, the type G of 1930 was also rear-engined, with the engine behind the rear axle, only a few were made. GWK's greatest days were before World War 1 and after 1918 financial success eluded them. They went into temporary liquidation in 1922 and Wood and Keiller left but Grice returned in 1923. No cars seem to have been made between 1926 and 1930 and very few of the Type G were produced. The company finally closed in 1931 with the Cordwallis factory being used by Streamline Cars Ltd and later Marendaz. GWK also sold an imported Belgian Imperia car between 1924 and 1928 as the British Imperia. There were plans to build the Imperia at Maidenhead but these came to nothing.

The GWK Chummy

In 1926, the last year of production under the old regime, the fabric-bodied 'chummy' GWK cost a mere £159, far less than the comparable Clyno models, but it seems as though the damning stories told of the unreliability of the friction drive had turned customers against the once successful GWK. In any case, the average driver of the 1920S was far better able to cope with a crash gearbox than his counterpart of a decade earlier, which tended to remove the marque's raison d' etre. There was one last attempt to revive the name of GWK in 1930, when Grice proposed to launch a new rear-engined model, but this never reached the public.

No longer could friction-drive enthusiasts question the presence of a gearbox on a light car. They said that the GWK substitute for shafts, pinions, forks, levers, dog-clutches and mush grease was in every way satisfactory. However, it could not, it seems, compete with the 'brusque and brutal' sliding gear transmission that Levassor had devised in the 1890s as a makeshift until something better came along.