The story of OSCA begins over half a century before the birth of the marque. An Italian engine driver's six sons, the Maserati brothers, became passionately involved with motor cars. They were Carlo, Bindo, Alfieri, Mario, Ettore and Ernesto. Carlo, the eldest, was chief test driver for Fiat before joining Bianchi, for whom he also raced. He died at the age of 30, by that time running the Junior car firm and being involved with the design and construction of aero engines.

Mario preferred a paintbrush to a spanner and became an artist. Alfieri began to race, while Bindo became test driver for Isotta Fraschini. After. World War 1, Officine Alfieri Maserati, which had started as a repair shop some years before, began to grow. Alfieri, Bindo and Ettore (who had been involved with Alfieri in the construction of a racing car in Argentina before the war) were joined by the youngest brother Ernesto (a wartime pilot) and the four designed, built and prepared racing cars.

For two years the brothers developed Isotta Fraschini machinery, then Diattos and finally, in 1926, cars which bore their own name,

Maseratis. The brothers lived a hand-to-mouth existence. They were far happier building the cars in the little factory at Bologna than attending to the administration. In 1932 they suffered their first major setback when their company's founder and head, Alfieri Maserati, died; he had never fully recovered from an operation following a crash in the

Targa Florio some years earlier.

Bindo, Ettore and Ernesto decided to carry on, the last-named now head of the firm which had built and sold some highly successful racing cars. The next crisis came in 1937. Sales dropped as the brothers' cars were not as competitive as before, one of the reasons being the domination of the German Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union teams in

Grands Prix. In financial difficulties, they sold out to two wealthy industrialists from Modena, Adolfo Orsi and his son Omer.

The Maseratis were retained on a 10-year contract and supervised the design and development of new models. In the early post-war years Maserati once more became one of the most prolific racing car manufacturers. In 1947 their contract to the Orsis expired, Bino, Ettore and Ernesto Maserati left Modena to return to Bologna where, with the minimum of capital, they established a new company in a portion of their old, pre-1937 factory. It was known as OSCA (Officine Specializzate Costruzioni Automobili Fratelli Maserati); the brothers had been forbidden to use their own name by the Orsis.

The intention was to revive the pre-Orsi days at Maserati by designing and building racing cars for the private owner. The three brothers - who did not drink, smoke or visit the theatre or cinema, such was their devotion to motor racing - started work with one lathe, one vertical drill, one shaper and one milling machine. The drawing office was Ernesto's bedroom. Ernesto was officially the development engineer, Ettore the tooling-up engineer and Bindo the plant manager. In 1948 their first machine appeared, an 1100cc sports car which was also raced with success in Formula Two. In Naples, Luigi Villoresi drove the car in Formula Two guise to victory ahead of such notable opposition as

Raymond Sommer (Ferrari) and

Alberto Ascari (Maserati).

Onlookers marvelled at the high standard of workmanship of the OSCA. The engine was a square (equal bore and stroke) four cylinder with a capacity of 1089cc. Its specification included a chain-driven single overhead camshaft, a light alloy

cylinder head and a fully-balanced five-bearing crankshaft. Two horizontal Weber carburettors were employed and a power output of 80 bhp at 6000 rpm quoted. The chassis frame comprised basically two large-diameter tubes braced by cross-members, a ladder-type arrangement that was the hallmark of the Maserati brothers. Front

suspension was by unequal length wishbones, torsion bars and dampers, while at the rear was found a rigid axle in a light alloy casing

sprung by half-elliptics.

Sarafini guies the 1342cc MT 4 OSCA during the 1949 Circuito del Garda.

Sarafini guies the 1342cc MT 4 OSCA during the 1949 Circuito del Garda.

1951 OSCA GP Car.

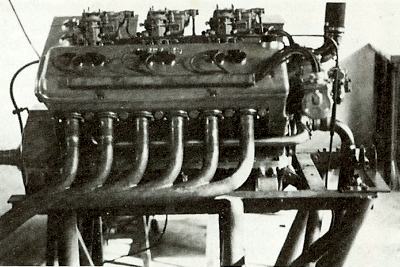

The OSCA 60 degree V12 GP Engine.

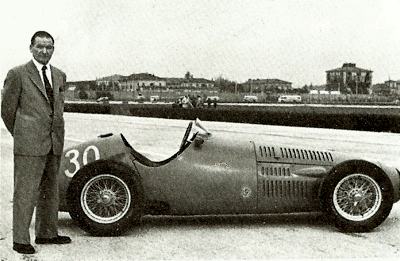

Ernesto Maserai standing next to the 1952 OSCA Formula 2 car.

Ernesto Maserai standing next to the 1952 OSCA Formula 2 car.

OSCA Land Speed Record car, which made a run at Utah in 1955.

OSCA Land Speed Record car, which made a run at Utah in 1955.

1960 OSCA 1000cc car as seen at Vallelunga.

1960 OSCA 1000cc car as seen at Vallelunga.

1962 OSCA GTS, which featured a 1600cc engine developing 100 bhp.

1962 OSCA GTS, which featured a 1600cc engine developing 100 bhp. |

Prince B. Bira

The same basic sports car design remained in production for years to come, with engines ranging in size from 750cc to 1.5 litres becoming available. But the Maseratis yearned to re-enter

Grand Prix racing and in

1951 the

Siamese Prince B. Bira commissioned them to design and build a 4.5-litre V12 engine to install in his Maserati 4CL T/48 chassis. By this time the 1.5-litre supercharged engine of the Maserati was out-classed in

Formula One and Bira hoped a more powerful engine - 330 bhp at 7000 rpm was quoted for the 60-degree V12 engine of 78 mm by 78 mm, 4472cc - would once more make the car competitive.

The OSCA's debut was at Goodwood on Easter Monday.

'Bira' won the Richmond Trophy

Formula One race and finished third in the Chichester Cup, also breaking the course lap record at 90.35 mph. At San Remo the

radiator was damaged in a collision and after finishing fourth at Bordeaux

Bira was third in his heat at

Silverstone; the final was curtailed owing to a downpour. At the Whitsun Goodwood meeting the OSCA won its heat, but in the final dropped out with

oil pump failure after raising the lap record to 92.12mph.

A skiing accident prevented

Bira from racing again until October, but a complete Formula One OSCA was on the grid for the Italian Grand Prix at Monza in September. Its chassis was of the familiar tubular ladder-frame construction, while the suspension was by unequal length wishbones plus coil springs and an

anti-roll bar at the front and by means of a de Dion tube located laterally by a Panhard rod at the rear. Driven by Franco Rol, it finished ninth and last, lapped 13 times by Ascari's winning Ferrari. The OSCA was plainly overweight and under-powered and only appeared again after conversion to a sports car.

Following the success of converted sports cars in Formula Two, new six-cylinder 2-litre single-seaters appeared in

1952 and

1953 driven by Elie Bayol and

Louis Chiron. The engine, a 1987cc unit with a bore and stroke of 76 mm by 73 mm, featured twin overhead camshafts and developed 160 bhp at 6500 rpm. Chiron won at Aix-les-Bains and finished second at Syracuse and Sables d'Olonne, while Bayol was second at Albi. At this time the Maseratis collaborated with the French Gordini firm; Gordini at one time considered building a Formula One car using the 4.5-litre V12 engine, while it was no coincidence that both OSCA's and Gordini's new Formula Two engines were originally going to be V8s but instead proved to be 'sixes'.

The Mille Miglia and Targa Florio

OSCA's chief successes came in sports car racing, especially in the rugged Italian road races such as the

Mille Miglia and

Targa Florio. From the original 1089cc engine were evolved the 1342cc (75mm x 76mm) model and the 1453cc (78mm x 76mm) version. It was in a 1.5-litre OSCA, owned by the American Briggs Cunningham, that

Stirling Moss and Bill Lloyd took a sensational, if brakeless, victory in the 1954

Sebring 12-hours in Florida. Their diminutive machine vanquished cars with many times its engine capacity. This success resulted in a host of enquiries from the United States and a new factory was opened in 1955 four miles south-east of Bologna at San Lazzaro di Savena.

By

1958 production had reached between 20 and 30 cars a year, all cars being hand built by the workforce of 40. One of the few items supplied by an outside concern was the bodywork. Three models were available, all sports cars, for the 750cc, 1100cc and 1500cc sports car classes. A development of the original engine of 10 years before, the Tipo 187 748cc unit developed 70 bhp; the Tipo 273 1092cc engine gave 95 bhp and the Tipo 372 1491cc over 135 bhp. All three featured two twin-choke Weber carburettors which fed the mixture into hemispherical combustion chambers with central Marelli plugs and two valves per cylinder. The twin overhead camshafts were driven by gears and a short chain.

Formula Junior

An experimental desmodromic valve 1490cc engine was seen from time to time in sports car racing and the 1.5-litre Formula Two of the late 1950s. It performed well, and reliably, but as there was no real power advantage gained in having mechanically rather than spring-closed valves the project was shelved. OSCA had to consider the service aspect - many of their customers were in the United States - and the cost. Towards the end of

1959 a new category opened the way for more OSCA sales. This was Formula Junior, a new single-seater class intended as a cheap introduction to motor racing for new drivers. Engines of 1 litre or 1100cc had to be derived from production units.

OSCA's answer was a front-engined machine of their usual ladder-frame construction. Front suspension was by unequal length wishbones and coil spring( damper units and a live axle was sprung by vertical coil springs at the rear. Power came from an OSCA-modified Fiat 1100 engine which developed a healthy 7Sbhp at 7500rpm. Works driver Colin Davies (a Briton who lived in Italy and the son of pre-war

Bentley exponent and journalist S. C. H. Davis) found plenty of success in Italian races in

1960, winning a so-called World Championship for Formula Junior cars run by an Italian magazine. But the writing was on the wall. Rear-engined, independently-suspended British machinery quickly got a stranglehold in Formula Junior and by

1961 the OSCAs were also-rans on the race tracks.

Alessandro de Tomaso

OSCA produced a 2-litre sports car featuring a four-cylinder engine of 55mm by 51.5mm (1995cc) which produced 175 bhp at 6500 rpm, but lack of funds prevented its proper development. In

1960 the 750cc sports car had a reworked engine, the Tipo 187N; it had a shorter stroke (64mm x 55mm), a completely revised

cylinder head and a power output raised to 75 bhp at 7700 rpm. A desmodromic-valve 1100cc engine was also made available to United States customers, while the It-litre engine found its way into Formula One cars designed and built by former OSCA customer Alessandro de Tomaso, an Argentinean living in Italy, but they lacked sufficient power.

Work progressed on a completely new Formula One engine design under the direction of Fabio Taglioni, of Ducati motorcycle fame, but this V8 (rumoured to be

air-cooled and with desmodromic valve gear) never saw the light of day and neither did OSCA's proposed spaceframe chassis (at last a rear-engined design). Into the 1960s OSCA concentrated on the production of a series of Grand Touring cars. The reason for this step dates back to

1959 when

Fiat asked to use the OSCA twin-cam sports car engine in their Farina-bodied 1200 model. Fiat built the engine in Turin, increasing the engine capacity to 1565cc (50 mm x 75 mm) and detuning it to produce 100 bhp at 6000 rpm. In turn, the Maserati brothers used the Fiat-produced engine (in more potent form) in cars of their own featuring

bodywork by such stylists as Touring, Fissore, Boneschi and Zagato, the last-named producing a sporting coupe.

Some OSCAs - notably the Zagato-bodied GTS with a 140 bhp engine - were raced, but no noteworthy successes were recorded on any of the world's circuits. In

1963 OSCA became part of the MV Agusta concern, a company specialising in the construction of helicopters. Its boss, Count Dominico Agusta, built and raced high-performance motor cycles as a hobby and there was speculation that with the acquisition of OSCA he might be tempted to challenge fellow Italian

Enzo Ferrari by building a Grand Prix car. As it was to transpire, this was not the case. OSCA GT models continued to be built for some time, while the ageing Maserati brothers experimented with various projects, but eventually production ceased and OSCA became part of motoring history.

Also see: The History of Maserati |

Maserati's Racing Pedigree