The Marquis of Rovin

The French

automobile builder Rovin was active from 1946 until

1959, although after

1953 production slowed to a trickle. The firm was established, initially as a motorcycle business, in 1921 by the racing driver and motorcycle constructor, Raoul Pegulu, Marquis of Rovin (1896 - 1949). The car was developed by Raoul but in 1946 production became the responsibility of his brother, Robert who continued to run the business after Raoul's death.

In the 1930s Rovin had turned his attention to a sportscar dealership which he established in Paris on the Boulevard Pereire. These premises were not suitable for auto-production on the scale foreseen, and in 1946 Rovin purchased the plant of Delaunay-Belleville, once famous as a luxury car maker and more recently also a builder of military trucks that had been deprived of customers by the dire state of the postwar economy and the return of peace to France. The plant was adapted to build small cheap cars more appropriate to the times.

Rovin Type D1

The prototype Rovin D1 was presented at the Paris Motor Show towards the end of 1946. The car was a very small cabriolet. It was powered by a single cylinder 260 cc

air-cooled four stroke engine. The engine's small size placed the car in the 2CV fiscal horse power category, and actual claimed power was only 6.5 hp. Supported by a three speed gear box, this permitted the manufacturer to claim a top speed of 70 km/h (44 mph). There were no doors, and the focus of sloping front of the car was a single headlight.

Rovin Type D2

It is not clear whether the D1 was ever sold in significant numbers, but production of the Rovin D2 started in 1947 at the company's newly acquired plant at Saint-Denis. The car still qualified (just) for the 2CV fiscal horse power category, but the engine was now a flat twin 423 cc four stroke water cooled unit. Claimed power output was now 10 hp and the car still featured a three speed gear box. Top speed was "between 70 and 80 km/h (44- 50 mph). The body was again very small, at just 2800 mm in length and with a 1700 mm wheelbase, and light-weight construction allowed for an empty weight of just 300 Kg. The vehicle now had two headlights. The engine was still at the back, but a small hatch in the body work right at the front of the car provided access to the battery. Although most sales were in France, the car was also advertised in the francophone western Swiss press and exhibited at the Geneva Motor Show early in 1948. During 1947 and 1948 approximately 700 D2s were produced.

Rovin Type D3

The D3 was little changed from the D2 under the skin, but the "skin" was an all new ponton format body with doors. The headlamps still stood out from the body, which presumably was a less costly solution than integrating them to the wings. The extra weight of doors and hinges and additional window did add some penalty and the car now weighted 380 kg. Nevertheless, a maximum speed of 75 km/h (47 mph) was claimed. Between 1948 and 1950 approximately 800 D3s were made.

Rovin Type D4

The D4 represented a mild evolution from the D3, with a larger front grille and the (still not integrated) headlights positioned a little higher. The two cylinder engine was enlarged to 462cc and now developed 13 hp. By now the overall length was 3150 mm on a wheelbase of 1800 mm. The gear box now featured four forward speeds and the top speed had increased to 85 km/h (53 mph). Minor cosmetic changes and suspension improvements were implemented towards the end of 1952. About 1,200 D4s were produced between

1950 and

1953, but in

1953 production had slumped to just 110. Although the model continued to be listed for several more years it is not clear how many, if any, were produced after this.

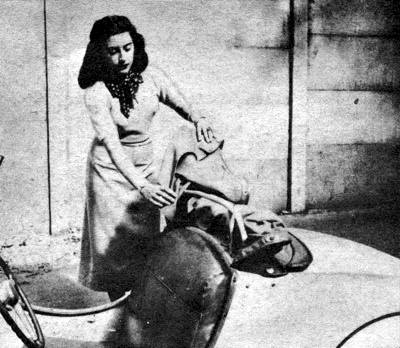

It might look elegant, but climbing in without doors was not so lady-like.

The Rovin top was an ingenious arrangement consisting of a metal frame, two sets of holes for "up" and "down" positions, and a canvas cover. Putting it up took about 5 minutes.

The canvas cover was tightly fitted and resisted attachment to two pegs on the outside of the windshield frame. The wiper was hand operated, and only worked when the top was down.

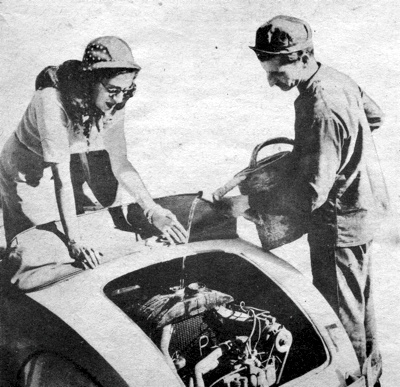

Filling the radiator of the 11 hp twin-cylinder Rovin engine. The engine was easily accessible, which was a good thing, because electrical connections were constantly being jarred loose by the rough roads.

The Rovin's fuel tank was just in front of the driver, beyond the dash. The spare tyre and big 12 volt battery were also stored up front. The Tools were kept behind the seat.

The Rovin dash contained only a speedo, starter, ignition, lights and turn indicator. It lacedk a fuel gauge, but you could hear the contents splashing about to determine how much was available.

Meanwhile little Rovin was easily parked in a nine-foot space. Getting in and out of the scooped doorway, however, required a certain amount of athletic skill.

|

Le Petit Rovin

by Diana Bartley

An American Tourist in France - first published 1954.

This is not a story about a love affair with a car. Even now, three years later, I feel somewhat ambiguous about the 11-hp, two-passenger French Rovin I bought in Europe to drive from Nice through Switzerland to Paris. Instead, this is a story about a slowly acquired affection for my little bright-yellow

automobile, which was the size of a child's toy and so mechanically simple that no boy-child would have the least difficulty with it. I am not, unfortunately, either a boy or a child.

When I arrived in Nice, late in June, 1 figured it would be both a good deal cheaper and a great deal more fun to drive through France than to take trains or planes. So after three weeks of dickering with auto-license, license-plate, registration, and government-stamp bureaus (none of which seemed to know anything about the others), I was persuaded by a very crafty

automobile dealer that, while the Rovin was tres amusant, it was also just the thing for la gentille mademoiselle to drive cheaply, comfortably, and sans difficult.

Nice to Avignon

The first difficulty I found was the reversal of the gearshift pattern. The second was trying to find the infinitesimal point along the two-inch length of the clutch pedal at which one could expect the clutch to engage suddenly. After that, I stopped counting. The first day's drive from Nice to Avignon was one of repeated and jerky stops and starts, with the motor constantly overheating. The engine would rev up to 3,200 rpm when the cylinders - both of them - were operating, but the cobblestone roads common to myriads of French villages were so rough that somewhere in transit through each of them at least one of the connections to the distributor head was jarred loose. (This may not have been the fault of the distributor, for those cars with normal-sized wheels rode over the top surfaces of the cobblestones, whereas the Rovin's tiny wheels bravely and doggedly negotiated each little hump.)

Unfortunately, it took me more than two weeks to find out what was wrong when the engine went putt-putt-putt instead of putt-putt-putt-putt-putt. And I suppose I paid an average of a dollar or two at least once every other day during that time before one kind mechanic explained to me that one needed only to remove the cap. scrape down the wire a little, then reconnect it and replace the cap. The third day, well on my way up the Rhone Valley toward Switzerland, I started to pass a truck on one of the two-lane, but smooth and beautiful, highways of the Midi. Suddenly I found myself in a motion similar to that of a small boat lying broadside to choppy waves. The trailer loomed high above me-and, as I veered toward it and away again, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the knowledge that its driver would never even know if I sideswiped his rear wheel.

There Was The Flat And There I Was

Finally, my head not even as high as the wheel and my heart in my mouth, I completed the pass. As I was recovering during the next half hour, I worried and wondered about why the car had acted "that way." Eventually I decided to stop for a few minutes to stretch - it was a lovely late Saturday afternoon - only to discover with horror that I had a completely flat rear

tyre. The

tyres were so small that on the straightaways there had been no indication of trouble in the

steering or

handling. But there was the flat and there I was.

An hour later, as I turned away from the road where I had been trying to flag down someone to help, I reached the conclusion that Frenchmen are not always gentlemen. (And it is only in America, as I learned from this and future experiences, that damsels in distress are rescued by knights disguised as truck drivers.) So I lifted out the back of die red-plastic banquette seat, fished gingerly around the floor, and came up with what were obviously, even to me, tools. Then I sat down and lit a cigarette to mull over how the tools might best be used to change a tire. To my delight, I had the silly little tire (which I could hold easily in one hand) completely changed before the cigarette had burned down - and I did it all alone!

A First Taste Of Mountain Driving

For the rest of that afternoon and the next morning, I climbed steadily up the western fringe of the Alps - my first taste of mountain driving. The motor needed a stop for cooling every hour or so, but "need" and "get" were two different things. Many times the road was so steep that I didn't dare to stop until I had reached the summit. After two headlong descents of about eight minutes each on mountains that had taken two to three hours to climb, I learned to let my motor brake for me. Like all mountain drivers, I gained a working knowledge of how to double clutch to get into a lower gear without losing too much speed.

And it was with the utmost relief and amazement that I finally realized that the little bug I was driving really wasn't going to slide back down the mountains in first gear. It may seem illogical to have had any worry on that score, but when you have poor brakes and only 11 hp, and arc not able to attain more than 5 km/h (about 3 mph) for several hours at a time, even on the comparatively shallow inclines - well, you are pretty soon convinced that this time you won't make it. When I arrived in Geneva, I found that none of the garages there had a new inner tube for my toy-sized tyre (I should have guessed by this point that they had never seen a Rovin before mine). I waited there several days while one garage patched up the punctured tube and fiddled around trying to tighten up the brakes and various other things - but such a to-do!

They warned me earnestly not to try any of the surrounding mountains with the car. I asked how they suggested that I get out of Geneva, which is ringed by mountains, and how they thought I got there in the first place. In answer to the first question, they said perhaps I'd just better stay. In answer to the second, they shrugged a "grace of God" reply.

The Chief Gendarme Of The Dijon Police

The trip to Paris - two full days of driving including detours - was relatively uneventful except that I made great practical use of my newly acquired mechanical knowledge. I changed

tyres twice; unwound, scraped, and rewound distributor-head wires several times a day; and readjusted the timing after each cobblestone village. I found and soldered a hole in the radiator when a "garage" attendant insisted there was none. I had a nasty little contretemps with the chief gendarme of the Dijon police, whose only but repeated words upon hearing about my catastrophic loss on the highway of my purse, passport, money, and French dictionary, were "Isn't that a shame!" (All were regained after typically French and truly incredible complications.)

And I became an authority on Monsieur Rovin's mistakes. A few examples? Well, the side-flap buttonholes were not placed anywhere near the stationary buttons designed for them on the car, the roof required a minimum of five minutes to put up, and the windshield wiper worked only when the roof was down-when it wasn't raining! I learned the above during a cold, driving rainstorm on a never-bring-you-back detour outside of Dijon (a town I do not yet regard with equanimity). But God is good - I also found the solution: visibility in rain was adequate with one's head out of the window.

What Idiot Would Buy This Car?

I hate to say this, but by the time I arrived in Paris I was very, very much out of love with Monsieur Rovin, his bright ideas, and garage-men who were supposed to know all about his car. I was not, furthermore, too particularly fond of any idiot who would pay $600 for one of the silly things ... namely me. It was finished neatly for me when the entire gear-and-clutch assembly simply ceased to function at all somewhere on the outside edge of Paris. It was Saturday afternoon, naturally. No garages were open and my Paris friends, not knowing when to expect me, had departed for the country, leaving a message that there were reservations for me at "a" hotel. That entrance into Paris was one of the most discouraging times I had with what I was beginning to refer to as "It." Things might have been easier if I had spoken decent French, but I doubt it.

At this point, I had owned the car just about three weeks. It was obvious that nothing more could possibly happen except for the neat little Fiat engine to just drop out on the road. (I was, as long as I owned the car, afraid to look to see how the engine was held in�really superstitious about it. I've always suspected that a non-waterproof glue was used and that I happened to be lucky.) It was even more obvious that, to enjoy "It" for the remainder of the summer, I would have to learn precisely what I was doing to its innards. The spit-and-hope process Was by now apparently not die right method for dependable functioning.

Negotiating Paris Traffic

As a matter of fact, though, it was about this time that the more pleasurable aspects of the Rovin began to be manifest. She could corner like nothing I've driven before or since - including the small

MG. The one-to-one braking ratio made for more work than I was accustomed to in Detroit cars, but a similar

steering ratio, along with a very low centre of gravity (she cleared about six inches off the ground), made possible almost unbelievable manoeuvrability. Even in the heaviest Parisian midday traffic, I putted around, in and out, back and forth, taking advantage of every yard-wide opening and consistently making much better time than the larger cars. (Of course, Paris traffic is so constituted that, while I could beat a

Citroen or a

Lancia through it, a bicycle rider would frequently make better time than I, and a man walking could often arrive at a given goal before any of us.)

I doubt that I would have been so daring in New York City or Los Angeles, hemmed in by Buick giants and Cadillac colossi, but I don't believe it is an exaggeration to say that in Paris one's driving success is closely correlated to just how far one is willing to back up what is said with the horn. Furthermore. I guess I really didn't know what I was doing because, just before I left Paris, I rode one time through the midday Place de I'Etoile traffic in a Buick. 1 was simultaneously appalled at the complexity of the traffic I had been buzzing around under, so to speak, and just plain frightened, a sensation unknown to me in the little car by that time.

The Rovin's suggested maximum speed, 75 kmph (about 47 mph), was misleading, for I once averaged that speed for three hours over approximately 225 km., more than 100 km, of which were heavily traversed approaches through the extensive outskirts of Paris. I had her up to 90 km/h (about 56 mph) several times. While that may not seem like flying to a

Jag driver, I suggest you reserve judgement until you try it seated a scant few inches above the road in a door-less toy.

Les Freins, Ilssont Pfttt

During the three summer months I had the Rovin, I learned how to twist my tongue around a whole mess of French automotive terminology. Such phrases as C'est necessaire faire quelque chose a la boite de vitesse ("Can you fix the gear box?") and Les freins, ilssont pfttt, ("The brakes are gone,") may be bad French, but they were a great deal more effective than my abortive attempts at mechanical sign language. At all times, identity with the red-up-holstered yellow midget was synonymous with being conspicuous. It took a while to get used to seeing 20 small French kids clustered around the car with wide, wide, covetous eyes whenever I returned from a restaurant.

Stopping for gas (the tank held 12 liters, enough for 400 km., averaging about 70 miles per gallon) was always enough provocation for a half-dozen wary French males to congregate. 1 learned eventually to smile sweetly when I said such things as, "Le deplacement du moteur est 425 cc.," and, "Oui, il y a un moteur a la derriere. Vons ne me croyez pas? Regardez!" ("Of course there's a motor in the back. You don't believe me? Look!")

More Fun Than Trouble ... Just

M. Rovin designed an improved version of his car the year I left France. It incorporated doors, a 20-litre gas tank, electric windshield wipers, and some luggage space. I have heard recently that a year after he marketed that model, he stopped manufacturing the car. If it is true, I certainly understand why, for with mine, at least a third of the requirements of a normal driver were lacking (oil and gas gauges, doors, luggage space, etc.), another third of those present never worked (windows, windshield wipers, etc.), and a large percentage of the remaining third functioned only sporadically (gears, brakes, starter, and spark plugs, among others).

But for all the greasy hands, gravel-scarred knees, rain-ruined clothes, and endless annoyances I suffered with my Rovin, in retrospect she looks pretty good to me. Quite honestly, she provided me with more fun than trouble, was a great convenience in the large and sprawling city of Paris, gave me a pleasanter and closer view of the French countryside that would have been possible any other way, and taught me more French than any high-powered American car or guided tour could have. Not only did I get to know her, but I acquired a sort of irritable affection for her - and I still miss her.