Today a convertible comes with a considerable overhead. Usually they are heavier because of the additional body structure required to eliminate scuttle, and the roof system is far more complex than a simple piece of tin. And all this means additional $$ on the showroom floor. But turn the clock back a hundred years and things were different...very different.

In fact, all cars could have been considered as "open" motoring. It was not until the 1920s that demand for closed

bodywork began to take hold, and coach builders were faced with several problems. For one thing, the closed body was heavy to build, and, for another, needed stout wooden pillars to support its roof; and, especially if metal-panelled (wood panelling was almost a thing of the past), it was prone to drum and magnify engine and transmission noise to a frustrating extent.

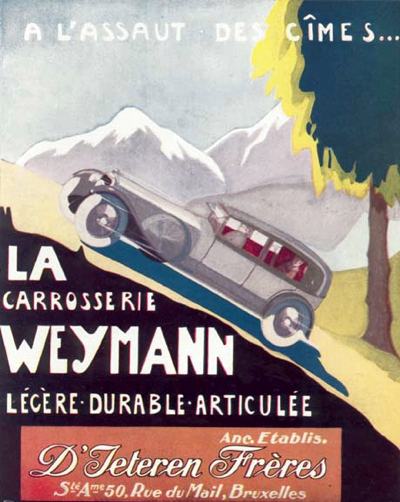

Charles T. Weymann

And, mounted on a chassis with the torsional rigidity of a cheap bed frame, even the most conscientiously constructed body was liable to flex, opening its joints, cracking its paint and generally becoming old before its time. That is why a Frenchman, Charles T. Weymann, devised a totally new method of body construction which owed nothing to the traditions of the coach-builder.

Weymann, whose works were at 20, Rue Troyon, Paris, was a maker of accessories as well as a carrossier, offering the ingenious 'Le Nivex' petrol gauge which was requisite for the dashboards of quality Continental cars of the era, as well as the 'L' Exhausteur' petrol pump. It was in 1922 that he revealed his new type of bodywork, in which the framing was made up of timber of narrow section which, instead of conventional jointing, was fastened together by light metal strips, permitting the structure to flex, as nowhere was there a direct wood-to-wood contact. And instead of metal panelling, the framework was covered in leathercloth stretched over padding.

1922 had seen quite a boom in the manufacture of leathercloths of various types, which, being available in standard widths, were an ideal covering for the new coachwork (though when Weymann-type coachwork reached England in 1924 the Cadogan Coachbuilding Company offered body-work of this type clad in real leather). The rise in popularity of Weymann coachwork was quite remarkable: in France around 600 bodies were supplied in 1923, a total that more than doubled the following year, soared to almost 5000 in 1925 and reached 13,000 in 1926. Weymann construction, with its need to keep contours as simple as possible-compound curvature was out of the question-imposed severe disciplines on the body stylist.

But because of this, it opened the way to a new school of coachwork design: and its influence spread throughout the car industry, as motoring artist F. Gordon Crosby commented in 1928: 'Probably no greater breakaway from the conventional in car design has ever been seen than in the influence of the modem Weymann and fabric-covered bodies. This influence has brought about recent developments, of which examples are the low, wide saloon, with almost rectangular outlines, higher, straight, bonnet lines, the narrow, yet deep radiator, and the complete absence of overhang both at front and rear.'

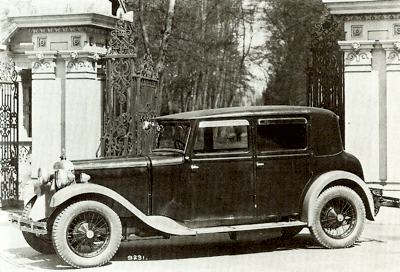

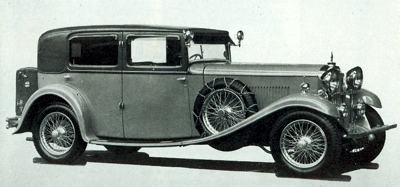

1929 Weymann 4 door saloon body, seen here on a Daimler 16/55 chassis. It was also available on a 20/70 chassis.

1929 Weymann 4 door saloon body, seen here on a Daimler 16/55 chassis. It was also available on a 20/70 chassis.

1929 Austin 20 Ambulance fitted with a Weymann body, as used by the St John's brigade.

1929 Austin 20 Ambulance fitted with a Weymann body, as used by the St John's brigade.

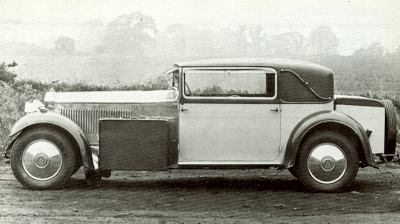

1931 Rolls-Royce with Weymann body.

1931 Rolls-Royce with Weymann body.

1931 Sunbeam 25 Monte Carlo Rally saloon with Weymann body. 1931 Sunbeam 25 Monte Carlo Rally saloon with Weymann body.

|

But the trend-setting qualities of the Weymann body also led to some awful deceptions. Manufacturers who were anxious to cash in on the Weymann cachet without paying the Weymann licence fee were quite liable to cover an ordinary coachbuilt body frame designed for metal panelling with a sandwich of chicken wire, horsehair and fabric, and pass the result off as 'Weymann-type', though it was as liable to squeak and fret as if it had metal panelling. There were even some whose 'fabric saloons' had metal panelling under glued-on leathercloth. Neither of these spurious types proved particularly durable; nor did they usually have the light weight of the genuine article - a fully-equipped Weymann saloon body weighed perhaps 4 cwt, a coach built body might scale two or three times as much.

Eric Gordon England

Weymann did, however, have a number of perfectly genuine competitors, whose products had considerable advantages of their own, like the aviation pioneer Eric Gordon England, whose approach to body-building was diametrically opposed to that of Weymann. Where the French manufacturer bolted a flexible body direct to a whippy chassis, Gordon England made rigid plywood bodies, covered them in fabric and then attached them to the chassis by means of flexible mountings. One advantage of this system was that a body constructed in this way could be panelled in metal, thus giving a shiny finish, whereas the saloon with a fabric covered body had, of necessity, a dull surface.

French manufacturers attempted to sidestep this drawback of the fabric body by using patterned leathercloth, often in violent Art Deco designs: for example, at the 1928 Boulogne Concours d'Elegance one of the entries was a Jean Graf with fabric saloon coachwork finished in a somewhat unwholesome looking tartan pattern. And, towards the end of the vogue for fabric

bodywork came a process whereby fabric could be cellulosed to give a kind of patent-leather look. This, it seems, was an expensive, but not popular finish, and was eclipsed by the introduction in 1929-1930 of M. Weymann's latest idea, the semi-panelled fabric body.

The Semi-Panelled Fabric Body

The semi-panelled fabric body was a more conventional construction, with aluminium panelling below the waistline, fabric above. This gave a more acceptable external finish, but seemed to be moving away from the original concepts of the Weymann body, as it was necessarily heavier in construction: typically, you could twist the door panels by applying force at either corner on the true Weymann coachwork; on the semi-panelled Weymann the doors were rigid. Indeed, it seems as though M. Weymann only came up with this idea to boost a rapidly declining market in France.

In England, however, the vogue for fabric coachwork was still popular, and new designs to rival the Weymann (whose British factory was at Addlestone, in Surrey) continued to appear. In late 1929, Vanden Plas, who were already active Weymann licensees, announced a new method of constructing flexible coachwork, which had been patented by one J. C. Penney, of St James's Square. This construction, which permitted the use of curved sections, was said to be both light and strong, and was used by Vanden Plas in the building of a two-seater body for Tim' Birkin's Bentley for the 1929 Brooklands 500 Miles race, 'largely because of the very light weight of a body so built, and the rapid manner in which any streamline curve can be schemed out'.

The J. C. Penney Body

Over a very light wood frame were laid thin spring-steel strips which took up the horizontal and vertical contours of the body. Where the vertical strips crossed over the horizontal ones, they were neither rivetted nor interlaced: little H-shaped aliminium clips linked the two strips flexibly, so that the body was highly resistant to twisting or impact. Over the spring steel frame was the normal canvas/padding/fabric sandwich which clad all fabric bodies. This type of body could be kicked and jumped on, it was claimed, yet would always return to its original shape: 'even in the event of a collision, it is most unlikely that the body would be damaged, while should the car capsize the driver would be protected inside a spring steel cage'.

Unfortunately the Bentley caught fire during the race, one eventuality that the ingenious Mr Penney had not provided for. But the day of the fabric body was now almost over. It had, indeed, been doomed almost from the start, as only a year or so after the first Weymann

bodywork had appeared, the Pressed Steel company had begun manufacture of rigid, all metal bodies that would eliminate all the faults of the conventionally coach-built car: and the success of this type was assured in the early 1930s when manufacturers became more concerned with the rigidity of their chassis.

The Pressed Steel Body spells the end of Weymann

A rigid metal body was as rattle-free as a flexible fabric one, though it might vibrate or drum; however, a fabric body had one major fault that could not be overcome; its covering was easily ripped and was difficult to repair. They said that replacing the fabric would be no more expensive than respraying a metal body: but a minor scrape could be expensive for a fabric-covered car where a steel body would need only a few pennies' worth of touch-up paint. After 1930, fabric bodies were rarely seen on touring cars, though some makers of high-performance sports cars, such as Lagonda, continued to offer light fabric saloons.

The 1931 Silent Travel Body

Weymann of Addlestone gradually slipped out of the car field, and concentrated on specialist commercial vehicle bodywork. However, the flexible body principle had one last manifestation when the Silent Travel body was launched in 1931. Adopted by many leading Continental and British manufacturers and coach builders, Silent Travel coachwork was panelled in metal, but had its framing built in sections - scuttle and windscreen, floor, door pillars, roof and hind quarters - flexibly linked by Silentbloc rubber bushes.

Said the popular scientist Professor A. M. Low, who had tested the Silent Travel coachwork with a Heath Robinsonian device called the Audiograph: 'In my opinion there is no doubt that the Silent Travel method of body construction represents a very distinct advance in

automobile coachwork. It is particularly trying, upon a long drive, to raise the voice or so to alter its characteristic and pitch as to render it audible above the creakings and rattlings of bodywork. By this new method of building, this difficulty is entirely avoided.'

But the steel body was capable of being rendered just as quiet, with a great deal less trouble. Both the Weymann fabric and metal-panelled Silent Travel bodies were soon outdated: though a faint echo of the Weymann era was still to be seen in the vinyl roofs fitted to cars of the late 1960's to mid 1970's. The Weymann body only lasted a decade or so: but its influence, in introducing coach builders to new materials and construction methods, was of the greatest importance in the history of coach building.