Arguably the greatest, and in the annals of motor-sport history, undoubtedly the best known team manager in motor racing was Alfred Neubauer. His large figure, festooned with stop watches and holding a red and black flag, was a familiar sight at

Grand Prix and sports-car races contested by Mercedes-Benz from 1926 to 1955.

Hermann Lang

Many was the time Neubauer threw his hat under the front wheels of a winning car from his team. Neubauer also had a knack of spotting budding champion drivers. He offered Hermann Lang, a mechanic, the chance to race a

Grand Prix car. Also, in the 1950s, when Mercedes-Benz returned triumphantly to

Grand Prix racing for two years, he chose drivers of the calibre of Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss.

Alfred Neubauer was born on 29 March 1891, in a northern province of Bohemia (which would ;ater become a part of Czechoslovakia), and at the age of seven his love affair with the motor car began: he saw a Benz and decided there and then that cars would be his life. In his late teens (when both his parents died), he joined the Austrian Army and, at the outbreak of World War 1, he fought at the front.

The Liaison Man at Austro-Daimler

Later he was transferred to act as a liaison man at the Austro-Daimler factory at Wiener-Neustadt where he befriended the managing director, Ferdinand Porsche. After the war, Neubauer was persuaded by Porsche to remain at Austro-Daimler as a production engineer and test driver. He also raced for them, driving a Porsche-designed Sascha 1100cc voiturette model in the

1922 Targa Florio. He was placed nineteenth and was the only survivor from the three-car team.

Mercedes Team Manager

In 1923 Porsche joined Mercedes in Stuttgart as a designer, and Neubauer went with him. Racing a 2-Iitre car in the 1924 Targa Florio, he took fifteenth place and third in class. He was fifth in the Semmering hill-climb and was a member of the Mercedes team in the Italian Grand Prix. In 1926, Neubauer became Mercedes team manager. It was the year Mercedes and Benz combined for financial reasons, which also resulted in the curtailment of their

Grand Prix racing programme. However, this was not before

Rudi Caracciola had won the first

German Grand Prix at Avus in Berlin, a race in which Neubauer introduced coloured-flag pit-signalling.

After

Rudi Caracciola won the Tour of Germany, a rally-type event, with a touring Mercedes 24/100/140, it was decided to utilise its 7.2-litre six-cylinder engine in a sports design. Thus the Mercedes-Benz K was born: With more power, the car was called the S and, with more power still (using the Rennsport motor), it became the SS, then with a shorter chassis it was known as the

SSK. The final racing version was the lightweight SSKL (super-sport-kurzleicht) with a supercharger that was engaged when the throttle was fully depressed.

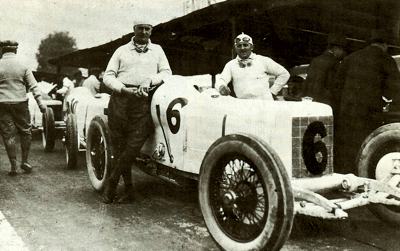

Alfred Neubauer with the Mercedes 2000 of 1924.

Alfred Neubauer with the Mercedes 2000 of 1924.

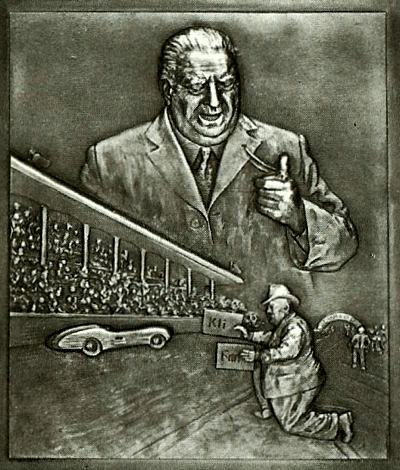

The Alfred Neubauer Trophy. One presented to Jochen Rindt in 1971 sold at a Christies auction in 2011 for £863 ($1,434).

The Alfred Neubauer Trophy. One presented to Jochen Rindt in 1971 sold at a Christies auction in 2011 for £863 ($1,434).

Neubauer with Moss and Jenkinson, winners of 1955 Mille Miglia.

Neubauer with Moss and Jenkinson, winners of 1955 Mille Miglia. |

Otto Merz

These S-series Mercedes-Benz were extremely successful in sports-car events, Rudi Caracciola winning the

Mille Miglia in 1931 (the first win in this classic by a non-Italian car or driver) and the 1929 Tourist Trophy at Dundrod. The cars also ran in Grands Prix run to free formula rules and, despite their bulk, they enjoyed some success. Otto Merz won the 1927

German Grand Prix and in 1928 and 1931 Rudi Caracciola triumphed in the same race. In 1932, the financial depression caused Mercedes-Benz to abandon their racing programme for two years. Then Adolf Hitler decided that Germany should be represented in

Grand Prix racing - for the greater glory of the Third Reich - and the Nazi regime sponsored both Mercedes-Benz and rival Auto Union.

Alfred Neubauer was back in business and, between 1934 and the outbreak of World War 2, the Mercedes-Benz team enjoyed 34

Grand Prix wins. In

1951 Mercedes-Benz made a return to racing, taking three pre-war type 3-litre W163 single-seaters to Argentina for two formula Libre events. The drivers were

Juan Manuel Fangio and Karl Kling, but the cars did not run well and were beaten on both occasions. The following year, prototypes of the 300SL sports car were raced. They competed in five races and won four - including a 1-2 victory in the Le Mans 24-hours - and were second in the fifth. These appearances were a prelude to a concerted Mercedes-Benz return to Formula One racing in 1954 to be followed by an attack on the World Sports Car Championship in 1955.

Fangio, Kling, Herrmann and Moss

Neubauer signed up Fangio to lead the team, supported by the Germans Karl Kling and Hans Herrmann. Stirling Moss joined them for 1955 and Neubauer rated him as the best post-war driver, preferring him to Fangio because of 'greater finesse and versatility' . The German cars proved superior to the chiefly Italian opposition, winning 11 of the 14 races contested with the Formula One cars in 1954-1955 and five of the six sports-car races contested in 1955 - the sixth, was the tragic Le Mans 24-hour race when the team was withdrawn following the fatal accident involving team driver Pierre Levegh and many spectators.

At the end of 1955, Mercedes-Benz - who had won the three major international championships (Formula One, sports cars and rallying) - announced their withdrawal from motor sport. Technical Director Fritz Nallinger said, 'We have all profited greatly by the experience gained in racing-car competition. Now, further developments of our production programme makes it advisable to employ our highly qualified personnel in the manufacture of production cars.'

Alfred Neubauer, by then aged 64, was no longer to run Mercedes racing activities. His portly twenty-stone figure and thunderous voice remained daunting, but at the very end of his career it was alleged his strong-arm tactics were deteriorating. In the 1955 sports-car season, there were reports of drivers arguing and slightly chaotic refuelling and tyre-changing pit stops. Neubauer always considered the Mercedes-Benz team as one big family: he insisted that team members ate together - and he had everyone's routine mapped-out, even to telling the drivers when to go to bed and when to rise. By using psychology, he smoothed out the problems of the more temperamental team drivers, but any who refused to obey orders were severely disciplined.

Rudi Caracciola

When Luigi Fagioli failed to obey signals to slow down during a battle for the lead, he was sacked from the team. However, one driver did spurn Neubauer and get away with it: Rudi Caracciola refused to go out on a record attempt, saying it was too windy. Neubauer was furious, as Mercedes' great rival Auto Union were preparing to despatch Bernd Rosemeyer. Rosemeyer's car was struck by a gust of wind, crashed and killed its driver. Few expenses were spared by Mercedes-Benz under Neubauer's direction.

When a leak developed in a

radiator at a British race, he telephoned Stuttgart and demanded a specialist welder to be flown to England. He was despatched from Germany, completed the job in three minutes and flew back to Germany almost immediately afterwards. For some years, Neubauer continued to travel to races out of interest, sometimes offering advice from his vast and detailed collection of data recorded over the years. He also assisted Mercedes-Benz with the racing exhibits in their motor museum before finally retiring to enjoy more the one hobby for which he had time during his motor-racing days: eating and drinking.

Also see: Farewells - Alfred Neubauer