All Three Tourist Trophies

We list Fred Dixon here in the Legends of Motorsport section of Unique Cars and Parts but, if we also had a legends of motorcycle section, he could have equally been listed there too. For forty-six years Fred Dixon divided almost equally between the car and motorcycle fields, the deeds of this prankish genius was the stuff of lengend, and why a movie has not been created about his exploits seems a travesty.

The success statistics alone make for impressive reading. Dixon was the only man ever to win all three Tourist Trophies - car, solo motorcycle and motorcyle with sidecar. He was the only driver to cop Britain's premier car classics of road and track, the TT and the

Brooklands 500, all in same season! His overall returns in the Royal Automobile Club's TT and the 500, two victories apiece, were never surpassed while he held a licence to race.

Freddie Dixon's second 500 win, in 1936, was turned at a substanially higher speed than the same year's Indianapolis 500, and had only once been topped (by 0.12mph) in the Hoosier series. His 2-litre

Riley, reworked to the point where it was more Dixon than Riley, was by far the smallest displacement unblown car to score a 130mph (209km/h) lap speed badge at

Brooklands.

The Fastest Motorcycle Rider In The World

Fred was first to turn

Brooklands at 10Omph (160km/h) on a motorcycle sidecar outfit, years ahead of the competition. Although his claim was disallowed on a technicality, he was, de facto, at one time the fastest motorcycle rider in the world. Later, a machine he had built and mothered gained another "meteorcyclist" the official world speed title.

But it would have taken more than mere success to put Dixon on the scaffold-high pedestal that his fans fabricated for him. They loved him for his defiance of every rule and convention in the book - social, legal and technical; his generosity to the younger, less experienced and worse heeled drivers who came to him for help and advice; his refusual to quit speedwork when, well on into middle age, his career was interrupted by a succession of really bad crashes; his unpredictable switches of mood, alternating between a devotion to labour on the one hand and bouts of crazy hooliganism on the other.

Stuck with a tough technical problem, he would work nonstop for four to five days at a stretch, catching a little sleep on the workshop floor at intervals between twenty and thirty hours, eating practically nothing and never noticing what he did eat, even foregoing all alcoholic comforts in favour of mugs of good old English Tea. When the task was completed, it was time to party, and his persona would switch back to the party animal, drinking more than any mere mortal should have been able, destroying the inside of a pub, including its furniture, and creating mayhem.

Record Holder, Pub Destroyer

History records that, while Freddie Dixon was a lot of trouble when on the turps, the Publicans at the time would tolerate much of the behaviour because they not only admired the man, but because he was amenable to reasoning and restraint such that he would always come back afterwards and pay for the damage he'd done - sometimes paying for a good deal more than he'd done. In race vicinities on the European continent, from Spa clear down to Madrid, restaurant keepers and hoteliers shruggingly accepted Freddie Dixon's prerogative to wreck and recompense.

Liberal as he was with his prize money and other professional earnings, Fred was no fool. Even after paying for his expensive fun, he usually managed to return home a richer man from his Continental capers. One of the few exceptions to this was an occasion when the promoters of a Belgian motorcycle race augmented their prize cheques with gifts of F.N. automatic pistols. Before Fred was through practising marksmanship, the doors, windows and panelwork of his hotel and adjoining premises were looking holier than a collander.

A Brit On A Harley

It needed the sad event of November 4th,

1956 to disprove the stock cliche that Dixon was indestructible. Certainly in his life-time he repeatedly lent weight to the fable, starting the very first time he raced at

Brooklands in 1921. This track debut also sowed the seeds of his reputation for resource and improvisation. The race was an 800 kilometres for motorcycles - an experiment in endurance that was never repeated, owing to the proved inability of men and machines to endure it. (Only one rider per entry was permitted.)

Fred's bike was a big Harley Davidson, lent by the British concessionaires for the Milwaukee make. By some mistake which was not uncovered until afterwards, the

steering geometry had been rigged for sidecar work, whereas this was a motorcycle without sidecar event. During training, Dixon found it impossible to maintain contact between his backside and the seat. So, making friction his substitute for science he scissored out a saddle-shaped sheet of sandpaper and glued it to the seat, abrasive side up. The dodge worked too, for a while. Then, 145 kilometres or so after the start, he felt a painful sensation in his bum. The sandpaper had rubbed clean through his horsehide breeches and was eroding his backside at the rate of a millimetre every two laps.

Sandpaper to the Backside

Thirty laps later, having made a pit stop and dispensed with artificial aids to stability, Fred Dixon took a dive over the handlebars when the front

tyre left the rim at 145 km/h. Dixon rolled himself into a ball in mid-air, looped a dozen ground-level loops on hitting the concrete, hobbled back to the Harley, kicked the bars and pegs straight, puttered to the pits on a bald front wheel, fitted a new

tyre and resumed the fray. He eventually placed second in a massacred field. Dixon, incidentally, was the only man to contest 500s on both two and four wheels. He was also unique in opposing the once-is-enough decision taken by the organisers of the motorcycle grind. Personally, he said, he hadn't found it very arduous.

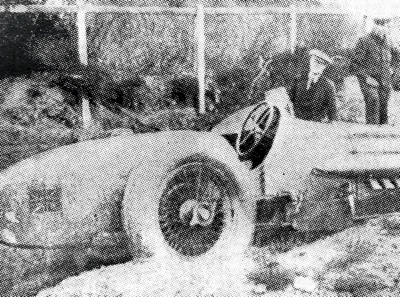

This famous shot shows Fred Dixon's Riley leaving the road in the 1932 Tourist Trophy race. Fred was tired after the customary all-night preperation, and nodded off. Luckily he woke quickly once he had become airborne, and had the mind to switch off the ignition before landing.

This famous shot shows Fred Dixon's Riley leaving the road in the 1932 Tourist Trophy race. Fred was tired after the customary all-night preperation, and nodded off. Luckily he woke quickly once he had become airborne, and had the mind to switch off the ignition before landing.

This 2-litre Riley, hand built by Dixon and his men, used a light alloy body bolted directly to the chassis to provide extra stiffening. This car still competes in British vintage racing events.

This 2-litre Riley, hand built by Dixon and his men, used a light alloy body bolted directly to the chassis to provide extra stiffening. This car still competes in British vintage racing events.

Aftermath of one of Dixon's few non-Riley ventures. While attempting to break speed records in the wet Dixon spun John Cobb's Napier Railton on the Montlehry track in France..

Aftermath of one of Dixon's few non-Riley ventures. While attempting to break speed records in the wet Dixon spun John Cobb's Napier Railton on the Montlehry track in France..

Dixon was a master of unblown engines but he ran his 2-litre Riley with a supercharger for a short time. This is the engine supercharger equipped.

|

The 1932 Tourist Trophy

Dixon's debut at his first car race culminated in a crash that had plenty of dram, such that the eventual winner hardly got any publicity. This was the 1932 Tourist Trophy, Britain's grandest eprevue, run over the old Ards circuit in Northern Ireland. Fred was forty years of age at the time and had quit motorcycle racing four years earlier. His car was an almost unrecognisable 1100cc Riley that he had bought secondhand less than three months before the TT and completely reconstructed, (with the sole exception of the engine-gear-box ensemble) in accordance with his own peculiar ideas.

That these ideas were effective as well as peculiar was sensationally demonstrated when, first time out for practice, he not only pulped the 1100 cc class record but also beat every 1.5-litre car in the list. As befitted the U.K.'s premier road race, the field included official makers' entries from all the British plants with an investment in speed,

Riley and

MG among them. It was against this background that a middle-aged roughneck from the north-country, with a car that visibly proclaimed its mixed status, threw down the challenge to the elite of British

automobile racing.

Indestructable Freddie Dixon

It didn't take long to see who was going to eat whose dust. Well before the first hour was up Fred led the whole race. Two hours, three hours, and he still was out in front. Then, around the fourth hour, the blackboard operator in his pit made an error, hanging out a signal that was a contradiction in numerals. Dixon, his nerves at snapping point from lack of sleep (he had worked to cure a last-minute engine fault throughout the previous night) did a double take. When it was too late he realised he was heading into a sharpish turn too fast to make it. Pointing the Riley at what looked like the least lethal piece of landscape, he went off the road at 130km/h, over-rode a shallow bank, tore a tree out of the ground and jumped a stream, 3 metres above water.

In midair, as a sharpshooting photographer was able to record, he had the presence of mind to switch off the ignition as an antifire precaution. Landing forty-five feet after takeoff, the car stayed right side, the driver's only injury being an enormous bruise on the broad bottom that, eleven years earlier, had survived its ordeal by sandpaper. His riding mechanic cut his face open on the dashboard. Another incident that furthered the "industructalble Dixon" lengend was written in 1934 at Donington Park, England, scene of

Auto Union vs.

Mercedes battles in the late 1930s.

Driving one of his full race 2-litre

Rileys, he was descending a fast slope to the circuit's one tight hairpin when the back axle casing disintegrated, carrying away both rear brake cables and snapping the prop-shaft. This time, all sections of the landscape being equally lethal, he slammed head on into a tree stump, a foot and a half high and about the same in diameter, at 180km/h. He returned to consciousness, with almost as many broken bones as whole ones and his already battered face purpled with fresh scars, ten days later. That, he figured, would be enough for one season, and the surgeons nodded grave agreement. In fact, unless he could get his nerve back it might even be enough for one lifetime.

Air Crash Investigation

His choice of a nerve restorer typified the perverse streak in his nature. Hating aeroplanes ("The darned things might fall down", he used to say) he went flying for the first time in his life. The flight achieved a momentum and altitude that was just sufficient to ensure the machine's total destruction and its occupants a severe roughing up when it nosedived into the ground a moment after take-off. For the second time in seven months, Fred lay unconscious for ten days. The fuel tank, mounted high up, had torn away from its moorings and crashed down on his head, it then splitting and covering him in petrol. That the wreckage did not catch fire was yet another miracle.

In his ability to extract reliable, economical power from small unsupercharged engines, Dixon was, in his day, without rivals. His knowledge was entirely self-taught. His education, which was of the elementary sort that came free in Britain, but ended in his thirteenth year. After that age, and presumably before it, it was doubtful whether, apart from technical works, he ever read what would be considered an intelligent book and probably not a dozen books of any sort. His accent was gutteral north-country, only half-way intelligible to fastidious southerners, and he never sounded an "h" or a "g" in his life. Yet within a year of breaking into car racing he was being approached by

automobile manufacturers. As a freelancer he always refused these offers, recalling with wry amusement that prior to forming his attachment to

Riley products, he had gone a-wooing around Britain's car industry, but in vain.

1955 Motor Racing Magazine

In a Dixon profile published in

1955 by Motor Racing, an English organ of speed sport, the writer weighed the ingredients of Fred's genius. Plain, straightforward, engineering knowledge and experience. An unusual capacity for sustained and concentrated thought, and a refusal to sidestep a problem until he had it ten-tenths licked. An ability to see the job in terms of first principles. A gift for orderly progression in applying his ideas, which he committed to paper before something cropped up to crowd them out of his mind. Disinclination to accept a practice for precedent on the mere grounds that that was how it'd always been done in the best circles.

An unfailing turning to account of his failures and setbacks. Why did this or that happen? What was the lesson behind it? Many years before he turned to cars, Dixon was among the pioneers of one carburettor per cylinder on motorcycle engines and he applied the same system to every full race Riley he built, fours and sixes to be rigged this way, certainly in the Britain. For all tuning purposes he regarded each cylinder as a separate engine, testing it individually on the brake and persevering until all outputs were precisely equal right along the firing line.

His carburettors were S.U.s by parentage but radically modified; the main difference consisted of using a single sliding plate throttle giving an absolutely unobstructed gas passage and mathematically matched opening and closure. The carb bodies themselves were bolted permanently to a heavy distortion-proof mounting plate, adjacent pairs sharing a common float chamber. At a date when the behaviour and condition of precarburetted air was a matter of apparent indifference to his rivals, Dixon had his S.U.s' intake mouths coupled to a sheet rubber respiratory chamber of calculated shape and capacity, ensuring a cool, plentiful and stable air supply.

The Dixon Rileys - No "Sprint Tune"

As a result of these and other carburetion measures, together with hairsplitting exactitudes in valve and spark timing, the Dixon Rileys not only out-powered all challengers of like displacement but set new standards of tracta-bility and low fuel consumption. Fred was contemptuous of what used to be known as "sprint tune". So far as his Rileys were concerned, the phrase was meaningless: apart from axle ratios, he ran them in one and the same state of tune in all events on his schedule, meaning everything from the 500 down to a thousand-yard hillclimb. Also, except when policy made it necessary to confuse the handicappers at Brooklands, he invariably drove flatout from start to finish of any race or record bid, no matter what its duration. If an engine wouldn't stand this treatment, he argued, it was time to find another that would.

Incidentally, in choosing to race the Riley six he acted against the advice of Victor Riley himself, head of the plant bearing his name. This mill had never been designed for speedwork in any case, and had in fact proved a flop in the few halfhearted attempts that Riley had made to whip a racing performance out of it. So far as the camshafts, pistons, manifold, conrods and carburettors were concerned, Dixon concurred in the maker's gloomy estimate of the design (for these components he designed and made replacements), but he nevertheless insisted that what was left had some germ of merit. And how right he was.

Fred Dixon Design

Dixon pioneered the low-down, horizontal air entry slot that became a frontal feature of many racing cars. He came up with that one as far back as 1932, causing consternation among traditionalists who asserted that the proper place for a radiator was out in the climate, untrammelled with tin-work. It wasn't until six years later, when Daimler-Benz followed this lead on their Grand Prix cars, that the detractors became quiet. As well as drastically restricting the airflow to his radiators (notably on the four-cylinder racers), Fred broke away from another fallacious practice of the '30s by omitting all louvres and other breachings from the top and sides of the hood.

This was expessly done for for two reasons, first to maintain an abnormally high air temperature around the

cylinder head and upper part of the block, with provedly benefical results; second to direct the outgoing air down around the crankcase walls, which louvre exits would have enabled it to bypass. That Dixon practised what he preached about "sprint tune" was shown by the fact that at

Brooklands he won his 130 mph (210km/h) lap speed badge in the 500. Ultimately he turned a lap on the 2-litre

Riley at nearly 135 (210km/h), less than 15km/h slower than John Cobbs outright record on the 21-litre Napier Railton.

The Railton and the

Riley were the only cars to win two 500s each. In the 1935 marathon, before Fred's Riley cracked up during co-driver Walter Handley's spell at the wheel, Dixon himself had turned a faster lap than any recorded that day by Cobb's mighty bolide, which finally won at 121.28mph (212km/h).

Fred's devices for ducking around irksome regulations were always good for laughs. To give himself enough thigh clearance in the pintsize cockpit of his 1100cc track race Riley, he sawed out the bottom arc of the

steering wheel. It was then pointed out to him that the rules demanded

steering wheels with a continuous periphery. It was that word periphery (they hadn't said circumference) that gave him an out. At the following meeting he showed up with a wheel the same shape as before but with the void bridged in with a straight bar. If the old one hadn't been safe, nor was this one, but it was technically unexceptionable.

The 1932 TT

His first car race of all, the 1932 TT, brought out the bush lawyer in Fred. The TT being for sports cars, the carrying of a spare wheel was compulsory. Non-standard bodies, on the other hand, were allowable, and the shell that Dixon planned was to be inches smaller than Riley's regular body in every dimension - so small in fact that there just wasn't room for a normal spare wheel in any undercover position; he didn't want to mount the thing outboard because it would increase weight and spoil the good aerodynamic shape of the tail.

His answer to this riddle was to buy an Austin Seven wheel at the junkyard and stow it with the tyre deflated. That way, it just went in. The rules, as he blandly reminded the furious scrutineer, didn't say the spare had to be of a size and make that would fit the car, or that the tyre must be pressurised. Himself, he had nothing to lose - a flat during the race would have killed his chances anyway. Back when he was racing motorcycles he adopted a handlebar windshield as a substitute for goggles. Like everything else he did, there was a reason for it. Snaefel Mountain, high-point of a bike TT circuit in the Isle of Man, was often capped in mist. In bad visibility he could take a succession of quick peeks out from behind his shield, whereas goggles were either up or down. Also, of course, raising and lowering them involved taking a hand off the handlebars at perhaps 160km/h. After a while, however, somebody remembered that the regulations said goggles must be worn. So Dixon bought himself a pair and took the lenses out. Nobody noticed.

Of less than average height he had broad shoulders and the muscles of a prizefighter. Around the tracks in his Riley days a favourite sideshow was watching him hoist a corner of the 2-litre car bodily into the air and hold it there, six or seven inches off the ground, while mechanics attended to some wheel or axle chore. During workouts in preparation for his 160km/h

Brooklands lap record with a cycle and sidecar, the outboard wheel came off at around the ton, Before the unsupported weight had time to hit the ground (it included a very frightened passenger who'd never ridden at race speeds before) he forced the machine over to an angle of lean where the sidecar was poised in precarious equilibrium three feet above the concrete. Holding it that way, he completed the lap without cutting the throttle.

Reducing the Weight

By diverse methods, including substituting Elektron metal for many ferrous parts, Dixon trimmed the weight of his Riley sixes to levels that no track car of comparable lap-speed had ever approached. This unique weight-speed ratio forced him onto a high-up strip of the bankings that had hitherto been considered the exclusive preserve of out-sizers like Cobb's Napier Railton and Oliver Bertram's 8-litre Barnato Hassan. These encroachments repeatedly put him in wrong with the stewards, a panel with a predominatly elderly and stuffed shirt membership. Fred's reaction to the ensuing reprimands and warnings was characteristic. If any steward thought he could get the darned thing around at 210km/h plus without using the high slopes, he was welcome to darned well try.

Another time, after winning a race on one of the

Brooklands road circuits, he incurred offical wrath by ignoring the check flag and making several extra laps on an otherwise empty track. The stewards thought this was just another example of his incurable propensity for horsing, and really let him have it. For once he gave them no back answers, maintaining what they probably considered an insolent silence. Years afterwards he told a motoring journalist the reason he had continued around the circuit. The race was his first after being released from hospital following his flying accident. The blow on the head from the plane's fuel tank had affected his eye muscles in a peculiar way. If he looked to right or left, it was only by a painful, slow-motion effort that he could focus straight ahead again.

Optometrists were consulted - and told him they couldn't do a thing to help. Not being prepared to quit speedwork at the height of a lucrative career, he decided to drive an experimental race with his eyes trained along the centreline of the hood from start to finish. The effort was so successful that he simply didn't see the man with the flag, and remained unaware of his paroxisms until the fellow almost threw himself into the Riley's path. Luckily for the blood pressure of

Brooklands officaldom, there was a Royal Automobile Club rule providing for the automatic withdrawal of a man's racing ticket if the law took his operator's licence away. And this the law eventually did, for the rest of Dixon's days, following a highway contretempts in which he asserted his well known individualism by punching a copper on the jaw.

Dixon Behind Bars

Just for that, in addition to having the open road closed to him, he did a spell in gaol, putting the stretch to a constructive use by livening up the carburetion of the prison cars. He also got permission to have draftsman's materials sent in and went to work designing one of the most remarkable automobiles ever conceived for the

Land Speed Record. He called it the Dart, which is exactly what it looked like on paper. It was to weigh not much more than 1360kg and had a planned speed of over 643km/h (this was about twelve years before the late John Cobb set the 634km/h record that is still unbeaten today). The 10-litre engine, which Dixon personally designed in detail, during and after his detention, was of "wobbleplate" rotary type and had the outward appearance of a toothpaste tube; its cross-sectional diameter, speaking from memory, was somewhere around 500mm. The car was never built.

This was Fred's second abortive

land speed record project. Earlier, he had bought and experimented with the Silver Bullet, a 500mm jinx built originally for a record bid by Kaye Don. Dixon finally decided that if the Bullet's

transmission broke up, as it was apparently liable to, it would certainly castrate the driver and probably divide him geometrically down the middle. For sheer audacity as an engineering concept, the Dart was perhaps only equalled by the Crab, a vehicle that Fred designed and built during World War 2 and afterwards developed over a period of years. In the prototype form it featured four wheel drive, all independent

suspension, a single

brake on the

transmission, and, most of all, unusual centrepoint

steering, like a kid's soapbox car.

There were other variants that went futher still, with

steering for both pairs of wheels and a device that automatically banked the wheels relative to the ground on turns. Even the prototype made conventional automobiles look literally silly in respect of hillclimbing - it would go up near-precipices without loss of traction - roadholding and braking. Upshot of this unique exercise was a long legal wrangle over patent rights that Fred either sold or didn't sell to millionaire industrialist Harry Ferguson. A short while before his death, Dixon accepted an out of court settlement of $40,000.

The last farewells to Fred Dixon were conducted in a way that would have warmed the life-loving old Yorkshireman's heart. Invited back to his home to partake of traditional funeral refreshments following his cremation, a gang of closer friends decided after an hour that it would be seemly to leave his widow to her grief, and prepared to take off. "What!", she said, "leave while there's all this liquor left undrunk? Did you ever know Fred to do a thing like that?" Come to think of it, they hadn't. So they didn't either...