Introduction

Rolls met a man named Royce in a commercial hotel in Manchester. From that meeting emerged a household word and a 20th-century synonym for excellence - a criterion of supreme quality. What word pre-1904 conversationalists used when they wanted to express the excellence of an article, before the name Rolls-Royce came into being, is hard to imagine. Today the name of that stately car, with its unchanging radiator - a symbol of tradition and wealth - is used by rich or poor to describe practically anything that has been built or made well.

Because of the name, the legend, the many years the expression has been in use - and perhaps because of that radiator - the words Rolls-Royce have an old-fashioned Edwardian tang about them. Yet there is nothing really old-fashioned about the cars themselves. The firm of Rolls-Royce had, from the very beginning, been intensely progressive - often ahead of their time. At improvisation and perfection of some piece of machinery or electrical gear already in use they have no equals.

Royce's Talent

Despite the present grandeur of the name, the man whose mechanical genius made this grandeur possible was of humble origin. Henry Royce was an electrical engineer. He came up the hard way, helping to support a family by selling newspapers at the age of ten. He worked, studied, and starved - alternately and together - while he accumulated knowledge and developed his talent for improving existing machines and instruments.

By 1903, when he bought a second-hand French car, he had become a prosperous manufacturer of dynamos and electric cranes. Typical of its day, the car was noisy, unreliable, crude, and inefficient. It appalled him - and his urge to improve turned to motor cars. With little knowledge of cars and none of their manufacture, he set about making three 10 h.p. two-cylinder models in a factory intended for making dynamos and cranes. Hand-picked mechanics and apprentices, some of whom are still alive, worked with him, making, adapting, experimenting, and testing. Much of the precision work Royce handled himself.

The first car was ready on April 1, 1904. A pull on the starting handle and it started - much to the amazement of those connected with the industry at that time. This easy-engine-starting was mainly due to an electrical system Royce himself had devised. The engine ran as efficiently as the starter that had kicked it into life. The car handled well, too - far better than most of its contemporaries. Clearly, Royce had produced an eminently saleable article; all he needed was the capital and the organisation to keep on producing and selling his cars. That's where the Rolls half of the name came in.

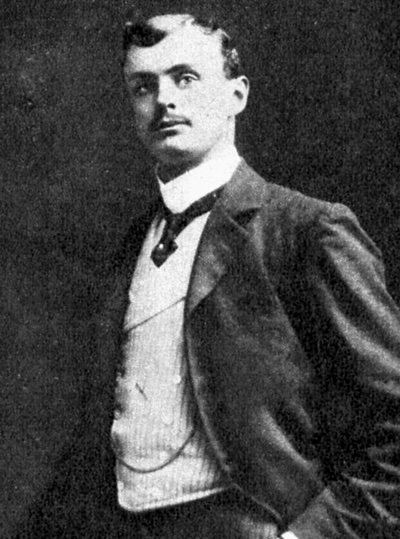

Charles Rolls shared Royce's passion for the automobile, and backed him with money.

Charles Rolls shared Royce's passion for the automobile, and backed him with money. |

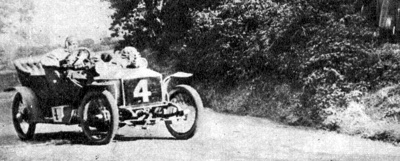

Rolls-Royce 20hp at the 1906 Isle of Man TT Race.

Rolls-Royce 20hp at the 1906 Isle of Man TT Race. |

Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost.

Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost. |

Wright Brothers with Charles Rolls riding in Silver Ghost.

Wright Brothers with Charles Rolls riding in Silver Ghost. |

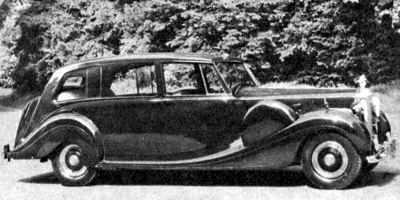

Queen Elizabeth's Once Owned This RR Phantom Four.

Queen Elizabeth's Once Owned This RR Phantom Four. |

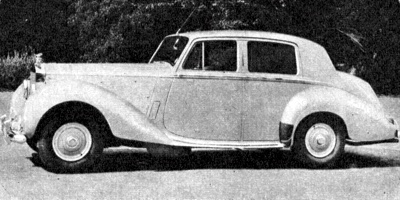

Rolls-Royce Silver Dawn.

Rolls-Royce Silver Dawn. |

Queen Elizabeth's Once Owned This RR Phantom Four.

Queen Elizabeth's Once Owned This RR Phantom Four. |

Rolls' Money

Unlike Henry Royce, the Hon. Charles Stewart Rolls came from wealthy, noble stock and was educated at Eton and Cambridge. He was the third son of Lord Llangattock; his family had a large estate in Monmouthshire, a town house, and an ocean-going yacht. But the conventional life of the leisured classes of Edwardian England was not for Charles Rolls. He took a degree in Mechanics and Applied Science, became one of the most knowledgeable and daring pioneer motorists at the turn of the century.

His motoring career began at 17, when his father took him abroad in 1894. From England, where a few "horseless carriages" crawled along the highways at four miles per hour, preceded by a man carrying a red flag, Rolls found himself in France, where motor cars had developed without restrictive speed limits, unhampered by the hostility of police and magistrates.

The cars young Rolls saw on the roads of France were a revelation to him. He bought a 3 h.p. Peugeot, brought it back to England and drove it to Cambridge, breaking the speed limit with an average of 4.5 miles per hour. A year later, in 1896, the law was changed, doing away with the man with the red flag and raising the speed limit to 12 miles per hour.

Rolls turned to racing and records - dashing from John o' Groats to Land's End in a Daimler in seven days in 1897; winning the first thousand-mile reliability trial in 1900 with a 12 h.p. Panhard; establishing a world speed record of 93 miles per hour while driving a 70 h.p. Mors at Dublin's Phoenix Park in 1903. In 1902, with an organising genius named Claude Johnson, he set up in business as C. S. Rolls & Co., selling the best Continental cars. After two years in business he was the leading car salesman in the country. He had orders on his books for over 100 cars—and not a British car on the market he considered good enough to handle.

The Meeting

As it happened that one of the first three cars built by Royce went to an acquaintance of Rolls - Henry Edmunds, now described as "the godfather of Rolls-Royce." Edmunds, a pioneer motorist and one of the founders of the Automobile Club, had just become a director of Royce Limited. He took Rolls to Manchester and they lunched with Royce at the Midland Hotel. Both men took to each other at sight - the engineer-perfectionist, and the seeker after motoring perfection.

Rolls saw the Royce car for himself, rode in it, drove it, and undertook to sell all the cars Royce could manufacture. The little car was exhibited for the first time at the Paris Salon and won a diploma and a gold medal. Rolls used it to drive the Duke of Gonnaught around on manoeuvres that summer. Royce, the maker, carried on experimenting and testing. Rolls, the salesman, was looking ahead.

A 10 h,p. two-cylinder car was not really what Rolls wanted. He sold cars to the "carriage trade." The wealthy aristocracy of Edwardian England was at that time slowly - but inevitably - changing over from the horse-drawn carriage to the horseless variety. This was a clientele to which the adventure and uncertainty of driving early motor cars did not appeal. It demanded reliability, comfort and silence. To that end Rolls began to feed Royce with ideas, suggestions and demands based on his own experience,

At Christmas, 1904, the now famous name of Rolls-Royce was born of a working agreement between C. S. Rolls Limited and Henry Royce Limited. By the following spring 15 h.p. three-cylinder and 20 h.p. four-cylinder Rolls-Royce cars were on the market, followed in a few months by a 30 h.p. six-cylinder model.

The Rolls influence was making itself felt: these were much more the type of car he wanted to sell. A comparison of the three models shows how rapidly Rolls was revolutionising Royce's ideas about cars. Royce, using all his skill and perseverance, was improving and developing towards mechanical perfection; Rolls was making the Rolls-Royce the fashionable car of the day and putting it on the map.

By 1906 Royce's production capacity was big enough to allow Rolls to drop all other makes of cars. Merging the two companies they founded Rolls-Royce Limited. Royce's old partner, Claremont, became chairman; Rolls was technical managing director, Johnson commercial managing director, Royce chief engineer and works director. Royce began to plan a move to new and larger works. Within a few months Rolls had won the Isle of Man T.T. race in a walk-over, driving a 20 h.p. Rolls-Royce. He followed this up by taking the car to New York and winning the five-mile race at the Empire City Track.

The Silver Ghost

While all this was going on, Royce was at work on yet another model - a 40/50 h.p. six-cylinder car which he believed to be the finest thing he had ever done. It was ready for the Motor Show in the autumn of 1906. With all its external metal work silver-plated, it was presented as the Silver Ghost. The Ghost gave the world a new vtandard of engineering excellence and motoring comfort. Its success prompted Rolls-Royce to adopt their simple but telling slogan - "the best car in the world." Its six-cylinder engine was cast in two blocks, had a square bore-stroke ratio and a maximum output of 48 b.h.p. at only 1200 r.p.m. It< compression ratio was 6.4 to 1, and it was the quietest car engine of its day.

Ever since then Rolls-Royce engines have left all others for' dead where silent operation is concerned. When U.S. car expert Wilbur Shaw road-tested a Rolls a couple of years ago, he thought the engine hadn't started when first turned on; it had —but he couldn't hear it, couldn't feel the slightest vibration. The soundless, effortless operation of Rolls-Royce engines is due largelv to the watch-like precision with which parts are matched together. From the outset Royce and his mechanics worked to the closest tolerances compatible with unrestricted motion; they also saw that all components were minutely balanced for weight distribution. No wonder their engines lasted.

While Royce was busy designing and producing cars, his restless partner began to find car racing too tame and looked for other worlds to conquer. Already an enthusiastic balloonist, he met the Wright brothers soon after they had invented the aeroplane. Here was a fresh and exciting challenge; Rolls promptly accepted it and became one of Britain's pioneer aviators. But the new sport was a perilous one. Rolls was killed at Bournemouth in 1910, earning the sad distinction of being the first Englishman- to die in a flying accident.

That same year Royce fell seriously ill; years of unremitting work and neglect of himself had taken their toll. Doctors ordered him to warmer climates, and he spent years in exile from his new factory at Derby. Surrounded by a team of experts he continued his work in the south of France and on the south coast of England, lie designed (he Eagle engine, Which powered more than half the Atlied aircraft in World War I and the first aircraft to make a non-stop flight across the Atlantic.

The war over, Rolls-Royce returned to the manufacture of cars, and Royce was largely responsible for the design of the Phantom T and Phantom II, which succeeded the Silver Ghost. In 1928 the Government " pressed the company to develop a racing aero engine. Three years later Royce (now a baronet) had the satisfaction of seeing his engine power the plane which won the Schneider Trophy outright for Britain. This was Sir Henry Rovce's last big triumph. He died in 1933— and ever since then the interlocked R's on the Rolls-Royce emblem have been enamelled black instead of the original red.

Tradition Lived On

Although its guiding genius had gone, the firm clung religiously to Royce's ideals of superlative engineering. They continued to turn out what they called "the best car in the world"—and it is significant that to this day no one has cared to challenge the truth of that slogan. The link with aircraft engineering was also maintained. In World War Tf the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, of which 150,000 were made, was the most-used power unit of the victorious Allied forces. It powered all Britain's fighter aircraft in the decisive Battle of Britain.

During the 1950s the Rolls-Royce factories at Derby and in Scotland produced engines for the aircraft of the jet age - for the Viscount and the larger Comets, which were in their day revolutionising air travel; for the Canberra, Valiant, Hunter, Swift. The Rolls-Royce cars, joined by the Bentley in 1931, were after WW2 made at the Rolls-Royce factory at Crewe. Every one of them was worthy of the tradition established by the Silver Ghost. With all this expansion, the factory which Royce built at Derby became the hub of the great organisation, and through Rolls' first workshop and garage at Earl's Court passed all Rolls-Royce and Bentley cars for export.