Looking Back On Forty Years of Motoring

by W. H. Lober

Ingenuity was alwayt the hallmark of success. To cope with rejection from the fledgling Australian Motor Industry, the message was clear, for Bill Lober. He would have to start his career overseas. Lober's story is from 1907 to 1947.

War-time developments and scientific advances, achieved because of the urgency of the demand to outstrip the enemy and irrespective of economic cost, have created expectations of almost fantastic speeds in the realm of transport. Jet propulsion is in the pencil-sketch stage for road-borne vehicles and even may have reached the drawing board; indeed, a newsreel recently showed a man experimenting on skis with jets on them!

Recently I celebrated the fortieth anniversary of the first issuance to me of a driving licence and so, at a time like this, one's mind is apt to become reflective on the many achievements of the human brain in catering for modern transport needs. In parenthesis, one is tempted to ask: ("Are we catering for those needs, or is it really the competitive element in mankind, the hope of reward which sweetens labour, that is responsible for the spending up of life during the past 60 years or so?") Maybe, a fair conclusion is that if there weren't a "market" there would be no offerings.

Nearly 50 years ago, in Melbourne, as a lad, I witnessed the advent of the first motor vehicles, little "one lunger" De Dions, Panhards, and the like, becoming wrathful, in my youthful enthusiasm, with those who would call out "Get a horse!" when the owner-driver, at the roadside, was attempting to coax some response from a lifeless engine. When the Oldsmobile buggy came first to Melbourne in 1903, it seemed to be the last word in ease of handling, smooth running and elegance. Little did I dream, then, of coming events casting their shadows! But try as I would, I could not secure a job at Tarrants, then the only motor firm of any consequence in Melbourne. So, nothing daunted, I made my way to England, in an effort to enter the motor trade.

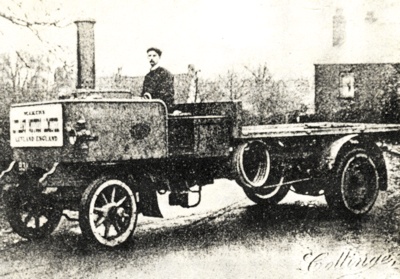

Being without funds, I was glad to land my first job as stoker and loader on a 5-ton steam wagon. There was the fine wage of 22/- per week for 60 hours, and time and a quarter over-time. As I secured board and lodging for 12/- per week, I felt in fine fettle, and the average of 80 hours work a week was relished because of the extra pay. And I still had time to look round to see where I was heading. With the advent of my eighteenth birthday I was eligible for a driving licence and then became a driver at 33/- for the 60 hours.

Looking back over the years, those early steam wagons were fearsome machines to handle. Five miles per hour was their legal and rated top speed; steel tyres on all four wheels; five revolutions of the steering handle for full lock on either side; and the driver had to keep his eye on steam pressure waterlevels in the boiler. A load of six tons was carried on the platform and four tons on the trailer. The steel wheels used to slip badly on greasy roads. There was a too-frequent experience of a headlong slide down a steep hill.

To change gear from top to low (there were only two speeds), it was necessary for the driver, before he started to climb a hill, to judge whether he could do it on top gear. If he felt he could not, he had to stop the vehicle, screw the hand-brake on with about half a dozen turns, then change gear, release the brake and start off afresh. If his judgment was bad and he had to stop on the hill to change, then it was an essential precaution to place two big chocks (which were always carried in a handy position) behind the rear wheels while the gear was changed. Yes, one's faculties were in whole-time demand!

In certain districts in England this speed limit of five miles per hour was very closely watched. Rattling along on iron tyres over stone paved roads, it was quite a job to determine whether one was exceeding it; of course, speedometers were unknown in those days and possibly would have been difficult to fit in any case. One particular district had a real terror of a speed-limit policeman. He would measure out his 220 yards, hide behind a hedge and, after we had passed, follow us on his bicycle, close up behind the loaded vehicle where he could not be seen and, at the end of his measured length, come out from behind and call upon us to stop.

Then he would calmly tell us that we had travelled the distance of 220 yards, one-eighth of a mile, at a speed of 5 1/4 or it might even be 5 1/2 miles per hour, and in the next few days a summons would be awaiting the driver. There was no appeal — one simply went before the Bench of Justices of the Peace, all honorary, of course, and to whom the merest statement by the police officer was the final word. In those days, the real fight was between the railway companies and this budding new form of competition, and we always assumed that the J's.P. were shareholders in the railway companies. Any attempt to dispute the briefest statement of the police officer generally resulted in the fine being increased from £2 to £5. Sometimes we would brief a solicitor to defend and if he was game to take on the case, he inevitably lost, even though he pointed out that there was no corroborative evidence that the 220 yards had been measured or that the speed had been properly timed before a witness.

Development Steam Bus Chassis, with W. H. Lober at the wheel.

The Steam Bus Chassis with body and livery, as used for deliveries in Accrington, England, before W. H. Lober's return to Australia.

|

Steam vs. Petrol

Then I got a job at Leyland Motors in Lancashire. That was at a crucial time in the history of mechanical road transport. Steam versus petrol - which way to go? In 1907, Leyland built a steam bus-chassis which it was hoped would remove the disabilities of the gearchanging, noisy unreliable petrol-driven buses then just beginning to make their values felt on the London streets. It was truly a delightful vehicle to drive and handle on the road. With its three cylinders, vertical and single-ended, and fitted with poppet valves, it was almost an engine designed for petrol, yet driven by steam. No gear-box was used, and with direct drive from the engine to the "diff." it glided along, on its rubber tyres, at 25 miles per hour as no heavy vehicle had ever been able to do previously.

But the London Licensing Authority would have none of it. The exhaust fumes from the boiler contaminated the air in the streets and try as they would, the manufacturers could not overcome this. So the project was abandoned, and petrol-driven vehicles became their future way of life and work. It was just about this time I had my first experience of driving a petrol vehicle. The waggon for factory use was an old experimental three-tonner — three-speed gear box, with a straight-pull-through change. One had to guess where the position was for the gears to mesh. My driving experience was nil, when I was instructed to go to the railway to collect a load of castings.

"But I have never driven a petrol vehicle!" I protested.

"Well, you are going to now," was the reply. "Get up and get those castings, quick and lively!" That is all the teaching I received.

Later on I had advanced sufficiently my knowledge of the intricacies of a petrol engine to get home one cold dark night, by using candle grease to make the engine run. It had cut out; the carburettor was in order, but I found that the insulation in the low-tension magneto had broken and exposed part of the armature winding. As the air temperature was about freezing point, I took off the bonnet and fan-belt, dropped some candle grease on the exposed wiring and wound her up. I got home, four miles, on that.

My first experience of driving a motor car came shortly after. It was a single cylinder Panhard-Levassor with tube ignition — the system used before low-tension was developed. The radiator consisted of a long length of fluted pipe which coiled up around the front of the dash, down alongside the bonnet, a couple of coils in front of the front axle and then up the other side of the dashboard where it returned to the intake on the engine. The car had no windscreen; no hood; the steering column was vertical; and two people could sit in the front. Two also could sit at the rear, each facing the other, access being gained by a door in what could be called the tail-board of the car.

The "Cape Cart Hood" and the Glass Windscreen

Shortly afterwards, Auster of Birmingham came out with two widely publicised innovations which were an immediate success - the "Cape Cart Hood" and the glass windscreen. Thereafter, by paying extra, the purchaser of a new car could have these highly desirable attachments fitted to his vehicle. That would be, I should judge, about 1907. I might explain that the "Cape Cart Hood" described one that could be folded down — just as it does today; prior to that, if one were fitted at all, it was a semi-fixture, clumsy to handle.

In 1909, Parry Thomas, a great figure in motor racing (he was subsequently killed racing on Presdine Sands) was very interested in developing a petrol-electric drive. He was a great gentleman, in every sense of the word; and many and many a time I worked over 100 hours a week with him. Once he got on to an idea, he would not let up. I was a mechanic's assistant and there were about four or five of us in his team. Sometimes we would go through from Monday morning to Wednesday evening without a break except for meals. Everyone was caught up with his enthusiasm, making this, testing that, trying something else, until Thomas was satisfied or disillusioned — and then to lodgings for a few hours sleep.

From what I could understand, in his petrol-electric drive failure came from the inability to overcome transmission losses of power. But one will ever remember the greatness of the man. Young and impressionable, I was quick to react to his moods, his inspiration and his born leadership, his fearlessness and kindliness. The world of motoring lost a great deal through his untimely death. Developments came thick and fast at this time. The Stepney wheel (spare) was a great boon, by allowed the tried and oft-times tired motorist a little chance to decide the time and place where he would mend his latest puncture. Acetylene headlamps by

Lucas made for safer night motoring, later helped further by compressed gas in cylinders, known as Prestolite. High tension ignition came into general use about 1908. But the greatest advance was in the laboratories of the steel makers their alloy steels gave the necessary lightness with added strength.

It was

Henry Ford who blazed this trail with his first

Model T's. The public did not understand the values of these high-quality alloy steels, and so, I believe, the spidery appearance of these old Ford T's did more than anything else to create those countless funny stories which were motoring currency in the days before and after World War I. But the Model T certainly made automotive history. About 1912, another comfort to the owner-driver was the invention of the vacuum tank by a firm at Coventry in England, whose name I cannot remember. They later took their patent to the United States and it was an immediate success until relatively a few years ago, when the electric pump displaced it. Before the vacuum tank came into use, the petrol tank was usually under the front seat, and we oldsters can well remember the days when the hill was too steep to allow the petrol to gravitate into the carburettor and it was necessary to turn the car round and ignominiously back it up to the top of the hill.

Then some of the manufacturers instituted a pressure feed from the tank to the carburettor by means of a hand operated air-pump fitted to the petrol tank. This system had its moments, too. One might be sailing along quite grandly and suddenly lose power ascending a hill. Why? Because the driver had forgotten to give a few strokes to the hand pump (which was conveniently fitted to the dash) and by the time the omission was corrected, the engine had stopped, and it became necessary to get out into the weather and "wind her up" again. In 1910 I had saved up sufficient money to pay a deposit on a secondhand waggon and became the proud owner (on terms) of the experimental steam 'bus, referred to earlier, which had been converted into a lorry to carry goods. And believe me, she earned her keep. With a load of four tons, that lorry could pass any petrol lorry on the road, uphill or on level going.

About this time, something new appeared on the horizon, presaging mighty changes in the world to come. At the Manchester Motor Show, suspended above the exhibits, was Bleriot's aeroplane, with which he had recently won the "Daily Mail's"prize of £10,000 for being the first to fly the English Channel — 22 miles! I can well remember gazing at it, going away, coming back, again and again, fascinated and wondering what it all meant. Its slender framework, the bare linen of its wings splashed with oil, its peculiar engine, all made one marvel at the intrepid, daring "flying man." At this Show in 1911, previously mentioned, another innovation attracted great attention. The Silvertown Tyre Co., of London, introduced their subsequently famous "Silvertown Cord Tyre." They had a unit of their machines operating to show how cord tyres were made, and it was only their greater cost which precluded a wider popularity. However, they sold well to owners of Rolls Royce and others of the more expensive cars.

It was not until American manufacturers, with their big volume were able to mass-produce them and simplify procedure, that the cord tyre came into popular use. Goodyear, I think, started before World War 1, but it was not until many long years after that that the cord tyre came into its own. Who remembers the Dunlop Company here taking a bold step with breath-taking advertisements that they "Now guaranteed their new Railroad tyres to do 3000 miles?" That was about 1919, I believe. It was a great achievement in those days when "wads" weren't what they are today. Many of us can still remember being sunk to the axles and having to be dragged out of "glue-pots" in wet weather, just the other side of the railway bridge at Flemington on the way to Parramatta.

At the Manchester Show previously referred to another star was rising, as yet small, but bright — another epoch-marking display which created great interest and discussion. In the university city of Oxford, a local bicycle-maker had "put together" a car which was the genesis of a type of manufacturing new to England. He had "assembled"it after purchasing the engines from White & Poppe, the axles from Wrigleys, the bodies from Austers, the wheels from Sankeys, and so on. His name was William Morris. There was much shaking of heads. How could he guarantee to deliver a good car when he did not make it, correctly speaking, himself? How could he rely on suppliers delivering the goods? But William Morris persisted. He sold them, and the public liked them, too.

Two or three years later, I had the pleasure of becoming his first agent in North East Lancashire and went to Oxford to take delivery of my "demonstrator, "the very week he shifted his tools from his bike shop in Oxford to a farm which he had acquired in the village of Cowley, three miles out. The bike shop would have had a frontage, I should say, of about 25 feet and a depth of not more than 60 feet. The farm at Cowley was a quagmire. It had been raining, and all that they had then had time to do was to put a new floor in the barn, the farm-house being used as the offices. The cow yard was literally over the shoes in mud.

I cannot be quite sure of the manufacturer's number of my car, but it was either 78 or 178. The car was then known, of course, as the "Morris Oxford," and it is interesting how the "Morris Cowley"got its name. When the 1914-18 War broke out, White & Poppe immediately went on to war work and the Morris source of supply for engines was cut off (prophets beware). Demand for Morris cars was insistent and the War Office, though not helpful, was demanding cars. William Morris went across to the United States and quickly arranged for supplies of engines from that country (as near to Morris specifications as possible) and probably for other components also. So that the difference between the "Oxford" and the new production would be known, the latter was christened the "Morris Cowley."

Fluid drive is not by any means new. I can well remember the Hele-Shaw people of Birmingham developing one in 1911 for fire engine purposes. The underlying idea was to enable the driver of the fire engine better to manipulate his speedy vehicle in traffic. But the Fire Board authorities, after exhaustive tests, would not permit it, as they felt it was somewhat complicated and might fail at a crucial moment. It was at this time, too, there was first introduced the turbine water pump for fire engines to replace reciptrocal pumps. That same Fire Board would not accept it for some years, because where water had to be drawn from a low level it was not positive enough in its initial pick-up. However, the idea was persisted with and eventually accepted.

In 1911 I drove an Argyll car which was fitted with front wheel brakes. This device was subsequently abandoned because the fittings sometimes had the tendency to lock on a turn, and the Argyll Company had not devised means of satisfactorily adjusting brakes on all four wheels to an even balance on the application of the pedal. It was not until 1924 that we received cars in Australia with four-wheel brakes. These, too, were of the mechanical type. Adjustments were troublesome to secure — and it was difficult, also, to maintain the correct proportions of pressure as between all four wheels. A year or so later the Lockheed people came out with hydraulic brakes. They proved to be the ideal system, one which has been continued in use up to the present.

Shock-absorbers originally came from Belgium. I cannot now remember the name of the first car to have them, but many old hands will recollect the old pre-1914 Lancia, with its big cylinders containing the coil springs, perched on the front and rear dumb-iron. In that period, also, Daimler introduced smaller coil springs to the rear shackles of all four main springs. The Du-Bonnet system, so well known here before World War II, is also a Belgium invention. It seems that Belgium has many stone paved roads which become irregular — "pot-holey," as we term it — and the demand in that country is always great for means to remove the discomforts so caused. From the old Lancia type to the present day, many forms have been tried, but it was not until the comparatively new hydraulic type was evolved, that the engineers have been able to overcome the real problem — that of unsprung weight.

Perhaps one of the most important additions to the first principles of motor car design which have persisted since the early days, was that of the self-starter. I think it was about 1913 that the Detroit Electrical Company (Delco) developed their combined, single unit generator and starter, and this, of course, proved to be of great value to the motorist. This appeared in Australia somewhere about 1915 (just before I returned to Australia) although there had been earlier types of self starter, mainly on the double unit principle of a generator separate from the starter. The older ones among us will remember the days of paint and varnish, and how the prices could vary from £5 for a cheap job to £50 for a really good coachwork finish. It was in 1924 that Duco first came to Australia from the United States, and the story of how it was developed is quite an interesting one.

During World War 1 determined efforts were made to preserve the linen or silk on the wings of aeroplanes which suffered badly by the action of rain and wind. Experiments were made with sheets of celluloid, but the problem of fixing these to the wings so that the air pressure would not break off the sheets was most difficult. Gumming the seams together with amyl-acetate was tried and then, I think, it was at Calshot (England) one of the scientifically trained men conceived the idea of dissolving the celluloid in amyl-acetate and spraying it on. This proved effective. It was a secret of the top drawer during World War I and became euphemistically known as "dope," the formula being retained until the war was over.

It remained for the Du Pont Company in the United States to develop this idea for the production of colour application in a way that would stand up to the demands of usage for motor car body work generally. When "Duco" first made its appearance here, those who then knew it will also recollect that for a year or two it had to be treated very tenderly. But Science, however, corrected the faults, and Duco became the standard treatment for body finish. In 1922 one of the General Motors ex-Presidents, either C.W. Nash or W.P. Chrysler, came out with a startling prediction, one that aroused the scepticism of all of us. He forecast that within a very short time the enclosed body, sedan and coupe, would be the standard body fitting, and that the tourer and roadster would be relegated to the background merely for sports models and young bloods.

However, in 1923 it was the Hudson Company that scooped the pool by announcing their "Coach," and I can well remember the astonishment in the Trade here as to how the Hudson and Essex enclosed body could be sold at the prices at which they were then announced. But by 1925 completely imported and luxurious sedans began to sell at a price close to that of the tourer. Then, indeed, we realised the worth of that prophecy. You know, gentle reader, how we of this modern motor world are apt to go into ecstasies about our new models. We wait for them with great expectations and we rapsodise about them to whosoever will listen. And yet, apart from "refinements," there is no real change in principles. True, there has been some evolution. But the "Otto Cycle" is still there, and the clutch, the gear box, the "diff' - all of them were used 50 years ago.

Improved, yes. But let us pause occasionally to take off our hats to those men of vision, who, alas, were too often scoffed at as mere "visionaries" - let us pay tribute to those men of inventive genius, who gave their knowledge and their money, only to be defeated when almost in sight of their goal. The long road, far back, is strewn with industrial skeletons; we of today have gained from the lessons of their defeats. We go our easy modern automotive way - unheeding? Or do we, as I hope, give an appreciative thought to the pioneers who achieved "so much for so many"?