The Pickle

MERCEDES-BENZ was officially out of motor racing in May 1932 when the Avus Race was held in Berlin - and their star driver was forced to switch to

Alfa Romeo. At that event

Rudi Caracciola drove a white Alfa but still ... it was the Italian flag that the honour guard hooked onto the mast during the last lap of this two-turn-endless-straight race.

What could stop Rudi's Alfa now? He'd led nearly the entire race easily from the likes of 4.9 Bugatti's and 16-cylinder Maserati's. A pair of "private" and aging Mercedes SSKLs, managed "privately" by the legendary

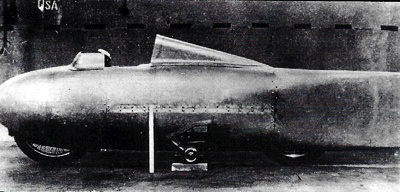

Neubauer, were considered make-weights at best or a good joke in the case of von Brauchitsch' car dubbed "the pickle" by the fans.

Koenig-Fachsenfeld

Even

Neubauer wanted to hide it, or at least put the old, upright, barn-door body back on once the bulbous cigar arrived by road from Vetter in Stuttgart where its wind-cheating body had been installed. Only a landed baron from Swabia, one Freiherr Reinhard Koenig-Fachsenfeld, believed in the shape. Of course that was understandable because he had designed it, the culmination up to that day of his passion for streamlining. Since young von Brauchitsch didn't have the ghost of a chance before his hometown crowd with the old SSKL anyway, he found the money (some from his mechanic) for a new body.

After one practice lap he was already regretting it - the car was un-driveable. Koenig-Fachsenfeld was later to recall, "I had already guaranteed it would be faster, which I could promise with no qualms. Now I explained he was going a LOT faster than the chassis was designed for and would have to drive himself in slowly. After a few more laps he leaped out, full of enthusiasm, saying the car was wonderful." The race was still no walkover and Fachsenfeld is sure the young ex-guards officer did a very clever tactical job.

Neubauer said (in his book) he had to tell the hot-headed youth he couldn't run away from

Caracciola. He should lurk just behind and save his pass for the final lap. Contemporary reports noted that Manfred did just that, apart from edging in front on lap eight to convince himself it was possible.

Von Brauchitsch

Caracciola carried a short lead into the second last turn on the last lap and the announcer proclaimed a sure Alfa victory. But it turned out that von Brauchitsch still had an ace. When his "streamlined" SSKL had proved 20 km/h faster than the standard model the mechanics cannily fitted it with a 2.2:1 axle, replacing 2.5, and he'd only used 3000 rpm all race. Now he cut in the remaining 600 revs, closed on Rudi, brushed by on the back straight grass and led over the line by 3.5 seconds. Koenig-Fachsenfeld considered this victory the turning point for streamlining - a fairy-tale finish which proved to the public that wind cheating could triumph over brute power or peak revs. Even the sneering press did a 180 to embrace streamlining. In both cases, earlier

Brooklands work was largely overlooked.

That "free" 20 km/h was equal to 80 extra hp, and von Brauchitsch even set a world 200 km record for the eight-litre class at 194.8 km/h. By comparison, Stuck in a newer SSKL fought hard to finish a distant fourth. In the midst of the hero worship few even noticed the pickle carried new Continental "slick" tyres as well. Local papers wondered if Mercedes would return to works racing. For the time being at least, it didn't, nor did young Manfred entirely trust the ungainly shape since he dismounted it for the next race on Nurburgring (and came third) although builder Vetter insisted there was no weight penalty and the wheels were visible anyway.

Streamlined BMW Mille-Miglia sedan, which improved wind resistance over opem MM cars by a factor of 1:1.6. The car was bodied in Italy, according to Koenig-Fachsenfeld, so that they could avoid his patents.

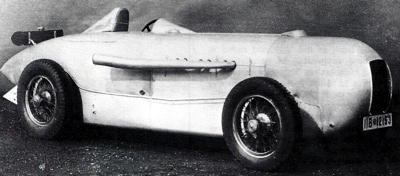

Von Brauchitsch car after Vetter rewrapped it. Special ducts were employed to ensure adequate cooling of vital components even on hot days.

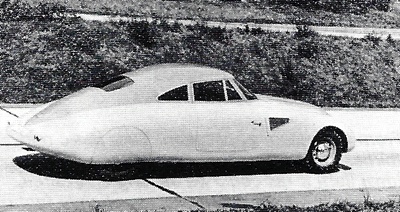

Streamlined Maybach undergoing Fulda tyre tests. This particular photo was taken just prior to the outbreak of the war.

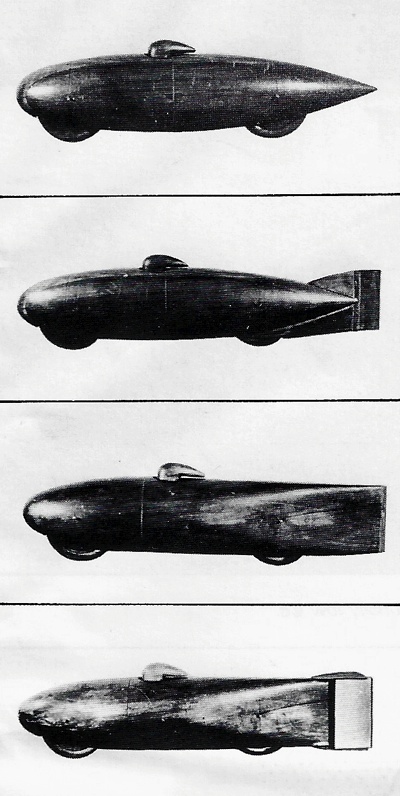

Above is a photo montage of the actual models used by Koenig-Fachsenfeld to develope the perfect streamlined shape.

The man himself, Koenig-Fachsenfeld pictured on his production bike. Koenig-Fachsenfeld was German champ for roadsters in 1924 racing.

The first "spindle" record bike, built for NSU who then ehied away from using it.

Bus design was the catalyst for developing the streamlined shape. The model in the picture features the K-Tail. |

Alfred Neubauer

Neubauer never ceased trying to disqualify the idea. During training he claimed his differential needed air to stay below 90 degrees so Fachsenfeld told a mechanic to take its temperature. "He came back grinning. 80 degrees. Neubauer wouldn't believe it but I told him to calm down. I had thought of that too and we had a vent in the undertray which cooled the axle far better than usual, it showed how important underside streamlining could be if you did it right." Avus gave first public testimony but the idea remained far from wide acceptance although Fachsenfeld had already worked on faired bikes and cars for more than a decade.

Out of the army in 1918, Koenig-Fachsenfeld skipped law or the military to study at Stuttgart's technical institute while racing English motorcycles and winning a German championship for production bikes in 1924. "But I soon realised no private racer could extract as much from his engine as the works and that forced me to consider reduced wind resistance. Jaray had the greatest influence on me because he had done the Zeppelins and I was interested in them. His studies are still basic today, but he was too far ahead of his time. And if you wouldn't do a car precisely as he said you couldn't do it at all.

"I just wanted to swing public taste a little. Even if a shape was a bit wrong it was still more streamlined than before. We didn't have to go 100 percent of the way at first. As a mix of engineer and realist it occurred to me next that we might make streamlining popular through records and racing." After 15 months in hospital when a car ran his road bike down, the landed gentleman turned to four wheels and captured 20 small-bore endurance records at Montlhery with a DKW in standard form, then some more with a

supercharged DKW 500 which did 140 km/h on 30 hp. This was still in the pointed-tail era and when these records failed to attract a public he looked for a more powerful tryout car. That was the Avus Ring Mercedes for 1932.

Unfortunately any SSKL chassis widened towards the back, "but it was the only chassis we had. Afterwards I wrote

Mercedes with suggestions for 1933 but it didn't accept them. Instead another car was built with only small changes and Merz was killed in that. I think he ran into side wind trouble but after that

Mercedes didn't want to hear any more, naturally enough."

In part this was still Neubauer's aversion to slippery shapes. Koenig told another tale of record runs near Frankfurt where the portly manager stuffed hundreds of pounds of lead into the nose of a purpose-built light car when it showed lift, ignoring

aerodynamic cures. After the Avus win "only private sport car owners showed even a little interest. It was the only way they could keep up.

The BMW 328 Chassis

"Wendler's works manager was keen about these cars of the future but his boss was less engaged. They built a few, mostly on BMW 328 chassis.

Tatra was the only firm which really tried and its shape wasn't perfect but it made me very happy they sold streamlining at all. The Adlers then were less ideal because the firm had to consider public taste even more but they were still very quick in what I called pseudo-streamlined form. "For the real thing you needed a rear-engined car, with front-wheel drive second-best." Koenig-Fachsenfeld did an Adler too, with sloping tail and less drag than the works Le Mans racers, but his attention was really on a whole new idea by the mid-thirties. It all began with bus models in the Stuttgart institute wind tunnel.

"A bus made sense because commercial owners cared more about saving fuel and buses have fairly smooth flanks with enclosed wheels anyway. But you couldn't let a pointed tail stick out five metres behind. The whole trick of good streamlining is really to hold the air flow along the roof and sides just as long as you can. Until it absolutely won't lie there any more. At that point we simply cut the bus off short and discovered it had a very good Cd (coefficient of drag). The bobbed tail was not ideal but merely the best system, with fewest objectionable features." And that was the second key point in Fachsenfeld's wind cheating career: the so-called K-form often called a "Kamm" tail for a Stuttgart professor of that name.

Doctor Kamm

In fact the patent for this seminal shape was registered not to Kamm but to none other than Freiherr Koenig-Fachsenfeld. He explained: "Too many bodies were drawn to a point much too rapidly, to look streamlined, and that caused eddies. Done right you even get more headroom - or an extra row of bus seats. It works best with enclosed wheels and you can always round off the edges a little for aesthetics.

All that matters is holding that air flow down as far back as you can." In figures taken from a car model the shape of an airfoil in side view, a taper ratio (from greatest cross section) of 3.5 proved best but gave too long a tail. Reducing the taper to 1.6 (steeper drop from roof line to road) increased Cd by 57 percent but cutting the tail off at the point where air lifted only increased Cd by 15 percent.

"So I registered the patent," and this was issued under the heading of "improvements in or relating to motor vehicles." The minute it was granted Fachsenfeld approached Auto Union about building such cars, only to be told they were

aerodynamically poor, inorganic and even ugly. If industry was doubtful some circles were more pointed. At that time Kamm (Professor Doctor Kamm of the Vehicle Development Institute) had proposed similar features in lectures.

While my patent was pending certain officials talked about protesting my primacy and so forth. I told them it was ridiculous to fight over this. We'd do it together. The institute had vast state funds so I worked on the job which was later popularly called the Kamm form. I couldn't get upset. It is much harder to put an idea across than to get it in the first place.

The Streamlined Maybach

"Anyway, it is hard to explain those times now. The Third Reich had just come in and I was never a supporter but they naturally had a great deal to do with the traffic ministry funds. And were never happy about me going my own way all the time. So I held back a little and the institute put our K-shape across. Most work then was rule of thumb. Later you might put models in the tunnel to prove the point.

Today it is fashionable to have big design staffs and wind tunnels for every door handle. You can do just about as well on paper. When

Hanomag wanted a car to set diesel records I did one and it took the marks. We could get special machines down to Cd values like 0.25, pretty close to Jaray's best with more space inside. But that meant covering the whole under-body and wheels. A road car today might get to 0.33 or 0.32 but not much less.

"The big Maybach for Fulda was probably my best job. They needed a very fast, very heavy car to test tyres and we got 240 km/h from the heaviest car in Germany. Dorr & Schreck built it and my only problem was getting Maybach people to lower the high radiator which wasn't needed anyway. But the car was barely completed before the war and it disappeared when the Americans came." You might have noticed that reduced fuel consumption has yet to be mentioned as a benefit of streamlining.

"Oh, we did a few tests to impress the head of some firm but nobody cared much then. There was one though; a rear-engined chassis with rubber suspension, a little 32 hp Ford engine and thermo-syphon cooling to avoid a radiator. The standard Ford with that engine just did 105 km/h; ours reached 140 km/h and got 17.5 km/I (49 mpg) at a steady 80 km/h. It was used as a courier car during the war.

War Intervenes

"Streamlining was ready for its breakthrough by 1939 but the war interrupted that." German motor magazines then ranked the slippery art second only to automobiles themselves among their land's contribution to motoring. "Afterwards it caught on slowly, mostly with the Italians. They even built the BMW

Mille Miglia cars down there to get around my patents."

The twin-rump Taruffi record car was a K-F patent and the

aerodynamically-minded estate owner did one more motorcycle after the war although he was largely finished with the art by then. "That went back to record runs in 1938. I had done some

BMW and DKW fairings but realised full shells were far too sensitive to side winds. We had to get the rider between the wheels, in what I called the spindle shape. After the war

NSU wanted the world record, about 300 km/h then, and I guaranteed my shape would do that with 60 hp. Since they had 90 with a blower it was a certainty.

"The chief engineer was excited with my drawings but he was replaced by Dr Froede. And Herz, who was to ride the bike, got hurt in a race. Other riders mistrusted the low seating and Dr Froede wouldn't even try it. Too dangerous. The bike never ran. Then, in the mid-1950s,

NSU spent a fortune on a Bonneville expedition and Herz actually went over 335 km/h with 90 hp in the old shape.

Just a few weeks later Johnny Allen broke that record easily with a Triumph engine which only gave 60 hp, using my sort of spindle form. Now all record bikes are that shape." Fachsenfeld turned from active

aerodynamics, distilled his experience into a four-volume works on the subject, then designed an agricultural trailer with wheels driven by a power takeoff from its Jeep tow vehicle. He never got to design a Zeppelin, nor even a boat or airplane, although he did produce one of the first streamlined bobsleds back in the 1920s and raced it.

He remained to his death totally without bitterness over setbacks or mis-directed fame. "Professors never like to take chances, you know. They wait until a practical man proves something they can safely put their name to."