We hope to bring you new and interesting content on our YouTube channel. Please support us by subscribing.

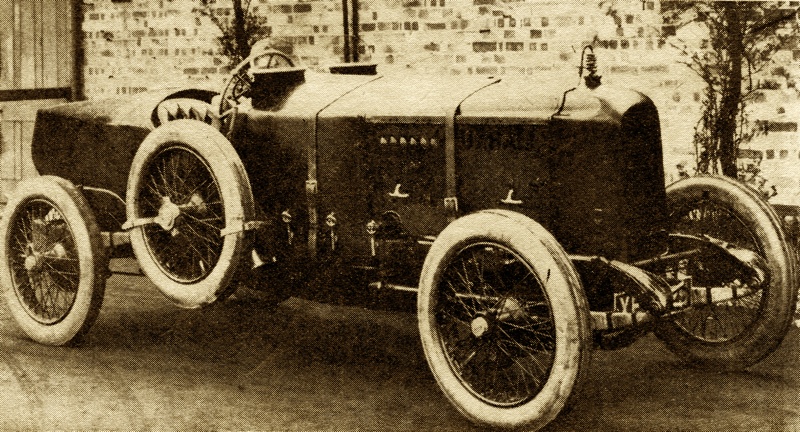

The Vauxhall TT MechanicalsIn practice, though, only one plug per cylinder was fitted, with central location. Contrary to general racing usage at that time, ignition was by coil and battery. (Unlike Duesenberg, whose contemporary racing mills also employed coils rather than magnetos, Ricardo dispensed with a generator.) The valves, operated through non-adjustable fingers, made an inclined angle of 90 deg., and all eight exhaust ports were separate. On carburetion, as in so many other departments, Sir Harry's thinking was way ahead of his time: from each barrel of a dual choke Zenith carb, one tract nourished a duet of cylinders, there being no connection between the two systems. Over on the exhaust side, Y-junctions cored in the head collected the spent gas for discharge through four downpipes. Stuck with the low octane fuel available at that date in those latitudes, Ricardo set his compression ratio at the very-low figure of 5.8 to 1. In spite of this, though, his plant developed 129 b.h.p. at 4500 r.p.m., which represented 0.72 b.h.p. per cubic inch. Actually, however, the merit of the achievement is best measured by the yardstick of power relative to piston area, in which light it much more closely approached modern levels for unblown racing engines. Each square inch of piston crown yielded a phenomenal 3.67 horsepower. Notwithstanding the large crank chamber capacity imposed by the indoor flywheel, the whole structure was enormously rigid, a factor contributing importantly to the high mechanical efficiency it realised - 80 per cent at 3,000 r.p.m. The Vauxhall TT Beats Sunbeam and BentleyFitted with the original two-seater body - deckhands were compulsory under the T.T. rules of the day - this three-litre Vauxhall had a top speed of around 115 m.p.h. Obedient to the destiny that seemed to ordain that Vauxhall's race projects should fail before they succeeded, the car flubbed its solitary T.T. strike. Out of the three machines that were fielded, one placed third, behind a Sunbeam and a Bentley, and at least one of the other two retired with minor engine derangements. Actually, though, in spite of their immaturity, the Vauxhalls were considerably faster than the victorious Sunbeam, this being demonstrated beyond doubt when one of the Vauxhall T.T.�s beat a T.T. Sunbeam by five m.p.h. in a straight fight at Brooklands later the same year. Although performance of the T.T. engine, right off the drawing board, was already high by the standards of its time, Ricardo, with a foresight and imagination that bore the mark of the mastermind, endowed his fledgling with tremendous margins for long-term development. For instance, the power plant of Raymond Mays' hill-climb car, variously designated the Vauxhall-Villiers and the Villiers-Supercharge, was finally made to develop 300 b.h.p. at 6,000 r.p.m., going up in gradual stages over a period of six years ending 1933. Major ingredient in this home-cooking exercise was an Amherst Villiers blower giving a maximum boost of 20 p.s.i. and fed through triple Zenith carburettors. Ricardo himself - and Vauxhall themselves- took no part in the several makeovers, which were the result of teamwork between Amherst Villiers (who also did much of the development work on the historic Blower Bentleys for Le Mans), Tom Murray Jamieson (who was later to design the two-o.h.c. Austin Seven engine) and Peter Berthon (subsequently the guiding technical intellect of the E.R.A. and B.R.M. ventures). With its relatively heavy reciprocating parts and piston velocity of 5,189 feet per minute at peak power, this supercharged version had an understandable reluctance to hold on to its top speed for very long. Once, when Mays was rash enough to keep his foot in the Zeniths for a complete lap during Brooklands tryouts, the entire car was seized with what he later described as "mechanical palsy". For agonising moments, during which the car was within inches of going over the top of the banking, the eyeballs of the terrified fellow travellers - Mays and Berthon were shaken around in their sockets so violently that they blacked clean out. On another occasion, and in a different place, Mays broke a crankshaft at 6,000 r.p.m., this being perhaps the only authenticated instance of fragments from a decimated engine landing in two different counties. (It's a pity to have to admit the car was practically straddling the county border at the time.) The T.T. Vauxhall's four-speed gearbox, as well as the cylinder/ crankcase block, was an aluminium alloy casting, a factor helping to keep the dry weight of an unmodified car down to the moderate figure of 2,464 lb. One of the many eye-opening chassis features was a rather complex braking system in which the normal pedal applied the front stoppers; a big hand-lever acted on the back wheels alone; and a little trigger on the steering post routed compressed air to all four pairs of shoes. Source of the breath for this servo system (of Westinghouse make) was a pump operated off the camshaft drive train. The theory was that in situations where the driver's hands, feet and eyebrows were fully occupied with other manipulative functions, he could just flick the trigger to on and leave it there until momentum was sufficiently spent. Or, in a pinch, he could delegate the Westinghouse finger-work to his riding mechanic Joseph Higginson, Autovac Inventor and Hill-Climb ChampIt somewhat over-simplifies the conception and birth of the lovely 30/98 sports car to say that "it came into existence by accident". Pomeroy himself provided the key to the enigma by adding that "it was never planned for production". True, it wasn't. A fellow named Joseph Higginson, inventor of the Autovac, was, at the beginning of last century's second decade, enjoying enviable successes as an amateur driver in English hill-climbs. But Joe had his frustrations, too, the chief of them being his recurrent failure to undercut the course record for Shelsley Walsh. At the time this was the blue ribbon of the hill-climb game in Britain. And the simple fact was that Higginson's huge and cumbersome 80 horsepower La Buire didn't have what Shelsley took. He therefore paid a series of calls on the best brains in the country's automobile industry, chequebook in hand, offering large sums for a car that would help him realise the ambition of a limetime. The only taker was Laurence Pomeroy Aine of Vauxhall, who, because Joseph hadn't given him enough time to start from scratch and create something entirely new, took the logical course of extracting some extra power from the best of his extant designs, the Prince Henry model. In the few months that were available, Pomeroy executed a masterly hop-up, boring and stroking the 95 by 140 m.m. P.H. job to the new dimensions of 98 by 150, and also adding other engine touches of a more subtle character. That was early in 1913. The recipe worked. Higginson, at his very first Shelsley Walsh appearance on a Vauxhall, set a record that was to survive until 1921, although the post-war climbs there were resumed in 1920. Enchanted with the results of Pomeroy's cuisine, Vauxhall forthwith built two more 30/98s in the approximate image of Joe's, turning one of them over to the company's managing director, P. C. Kidner, and the other to their established professional race driver, A. J. Hancock. These cars were immediately successful in speed work and, before anyone quite knew what was happening, the model had crystallised into a limited-numbers production type. The Vauxhall 30/98 E-TypeIn keeping with its almost haphazard entry into the world was the fact that even the people most closely concerned with the 30/98 were never exactly sure how the car came by its designation. It was then, and remained for years afterwards, a favourite nomenclative practice in Britain to make up type numbers out of two sets of numerals with an oblique between them, the prefix denoting the nominal horsepower under the English fiscal system, and the suffix the output in b.h.p., real or fictitious. But the 30/98 never was fiscally rated at 30, and it never developed 98 on the dynamometer. One theory is the engine developed 30 b.h.p. at 1000 r.p.m. and. that the 98 referred to the bore measurement. But presently the Vauxhall company is not dogmatic on the point, allowing that anybody's guess is as good as anybody else's, and possibly better! Superficial scrutiny, or even a much closer study, fails to reveal even a few obvious reasons why the original L-head 30/98, known as the E Type and displacing 4,526 c.c., produced more power than contemporaries of comparable capacity, and did so with such smoothness and lack of effort. It just did, that's all - in common with all the creations of chief engineer Laurence H. Pomeroy. Basically the prescription was straightforward enough: side valves, a five bearing crank, fixed cylinder head, single riser carb, iron pistons, a compression ratio that presumably wasn't higher than 5 to 1, a chain-driven camshaft with the sprockets at the front. Nevertheless, his unpretentious movement churned an honest 90 b.h.p. at 2800 r.p.m., giving the car a top speed of around 85 m.p.h. when fitted with what became the classic 30/98 body � an open sports four-seater of trim and slender shape, known as the Velox. Pomeroy's handiwork in 1913, like Ricardo's nine years later, certainly showed a shrewd appreciation of the importance of good cylinder filling and structural rigidity. His cams for the E Type engine gave a higher lift than was probably to be found on any non-racing mill of the period, while incidentally, his valve clearances, at .050 and .060 in. for intake and exhaust respectively, were truly jumbo voids. Something else in common between the brain progeny of Pomeroy and Ricardo was their responsiveness to advanced tuning and development. The E Type 30/98, which was promoted to full production status after the first World War, won countless speed events in Britain and abroad during the 1920s. What power output was eventually achieved isn't easy to say, but it's a fair guess that the single seated E that lapped Brooklands at 108 m.p.h. must have jerked the dynamometer well into three figures. The Second Anglo-U.S. Vintage RallyThey were stayers, too, these E Types. Running over atrocious roads, one heavily-crewed example averaged a record breaking 40 m.p.h. from Durban to Pretoria. Earlier, one of the half-dozen Es turned out before WW! had had the memorable distinction of placing second in the 1914 Russian Grand Prix at 70.8 m.p.h. mean. What this race was, or where it happened, is obscure, for not even Monkhouse's encyclopaedic Grand Prix Facts and Figures mentions it. Although there are fewer 30/98s than vintage Bentleys in captivity, these classic Vauxhalls are at least as eagerly sought after and reverently preserved by connoisseurs the world over. Needless to say, the relative virtues and potencies of the 30/98 and the unblown 4i Bentley are argued and reargued with a fervour that induces suicidal boredom in non-partisans. In vintage competitions of the present day, sometimes one will win, sometimes the other. But anyway, the results prove little or nothing about the original merits of the two designs, because examples now surviving are all practically certain to have benefited from injections of modern technical knowledge and lavish financial outlay. Incidentally, it won't have escaped the notice of devotees of the classic automobile that two Vauxhalls, a 1914 Prince Henry and a 1920 30/98, were among the eight cars chosen to represent Britain in the second Anglo-U.S. Vintage Rally, run over a test-punctuated course in the States of New York, New Jersey. Pennsylvania, Connecticut and Massachusetts in April of 1957. The 30/98 made fastest time, irrespective of displacement or nationality, in a speed hill-climb over the 2.5 mile Duryea Drive course at Reading, Penn., and also won the standing quarter-mile sprint with a time of 19.9 seconds. Anything under 20 seconds for a standing quarter by a 35-year-old L-header is not to be despised, no matter what loving care has been bestowed on it. Vauxhall 30/98s fall into two subtypes - the side-valve E model and the OE with pushrod overhead valves. The latter, still with a 98 m.m. bore but its stroke reduced to 140, was launched early in 1923 and gave 112 b.h.p. at the increased crank speed of 3,500 r.p.m. Regular OEs, curiously enough, were little if any faster than the L-headed son of a German prince, presumably due to the slight gains in weight and the girth that accompanied the switch to o.h.v. On the other hand, the push-rod design brought real improvements in flexibility throughout the speed range and would throttle back to six m.p.h. on its 3.3 to 1 top gear without snatch with a full four-person crew aboard. At birth, the OE was braked on the back wheels only, same as the E Type had been, but front brakes, featuring heavily ribbed drums of imposing measurements, were added in the autumn of 1923. The "Bent-Wire" CrankA later development was the introduction in 1926 of a counterbalanced crankshaft, superseding what was disrespectfully known as the "bent wire" crank. This, by moving the safe r.p.m. limit up the scale, much increased the scope for ho-pups. From the dates quoted here it will be apparent that G.M.C., to their credit, did not immediately junk the 30/98 on taking over at the Vauxhall plant, sited at Luton, Bedfordshire, in 1925. Indeed, although the Detroit influence foreshadowed Vauxhall's erasure of the sports car from their catalogue, the finishing touches were put to the OE by engineers working under G.M.C. orders. These included the conversion of the brakes to hydraulic operation in 1927 - the 30/98's last year in production - and the redesigning of the fuel filler orfice to cure it of its notorious habit of regurgitating about half of its intended intake onto the ground. It needs more than a respectable specific output, or even a vigorous power-weight ratio, to make a great car, of course, and the 30/98 possessed the necessary additional prerequisites of greatness. It was superbly made from the finest materials. The general readability, with the possible exception of the earliest OE, which was a mite short in the wheelbase and therefore had a tendency to skid in the wet, was of the highest order. The layout of all the engineering elements was neat, orderly and accessible to a degree that even Bentley couldn't surpass. Every car was exhaustively and expensively tested before leaving Luton: engines were run for impressive durations on the bench, then the cars were placed on a roller rig and operated in all gears in turn under conditions simulating street work. Finally there was a normal road-test routine. Well might the Motor remark, in reports published in 1919 and 1920, that the 30/98 was "a car containing all the essentials of a racing model without the usual accompaniment of harshness and excessive noise"; and that it represented "a new conception of what the sportsman's motor car should be." The external hallmark of Luton was always the distinctive fluted gouging tapering rearwards from the radiator shell into the bonnet shoulders. These flutes originated back before World War 1. Bodywork for the 30/98s was meticulously made and finished, the paint jobs being individually blanketed in airstreams from multiple ovens permitting precise control of temperature and humidity. In general, the design of the Vauxhall bodies of yester year did not show any daring originality, though there was one exception: in collaboration with the Earl of Ranfurly, who apparently couldn't quite bring himself to say adieu to the era of horse-drawn transportation, Vauxhall once built a number of motorised hansoms, thereby setting a record for driving seat altitude in automobiles. These vertiginous buggies were not a commercial success and died a quick death. The Vauxhall Prince HenryThe Vauxhall Iron Works Company Limited first went into business as car manufacturers in 1903, but the marque's real origins go back more than a century, to 1857. It was then that the Vauxhall Iron Works was established for the production of marine engines, taking its name from the London district that it neighboured. Long before the 30/98's accidental emergence, Vauxhalls of various shapes and calibres had made their mark in trials and racing. The celebrated Prince Henry model, for instance, won its spurs and its label in the Anglo-German match event of 1910 known as the Prince Henry of Prussia Tour, after its royal patron and participant. The" 4 litre P.H., from whose loins the sidevalve 30/98 sprang, can fairly be regarded as the prototype of the British sports car, and continued in production until the end of the first war. Vauxhalls were consistently innovative and automotive leaders at Brooklands in the old track's infancy, marking an aerodynamic epoch with their razor-blade single-seat bodies. These fresh concepts in streamlining led to frontal area reductions of over 30 per cent, and "K.N.", king of the Edwardian monopostos, hit a new low in this department with a cross section of less than eleven square feet. "K.N.", in 1910, was the first car to reach 100 m.p.h. in Britain. Aware of the need to minimise internal as well as external drag, Vauxhall made their historic century run with the gearbox and back axle drained of oil, thereby just cajoling 60 b.h.p. into penetrating the three-figure barrier lor a distance of a half-mile. An attempt by A. J. Hancock, the Vauxhall works driver, on the world's 12 hour record in 1913, using a special single-place Prince Henry. During pit stops, it is recorded without comment, as though it were a perfectly natural matter, Hancock had his face washed by chief engineer Pomeroy himself in champagne. If they used the stuff for ablutions it is fascinating to speculate what Hancock and his obedient servants actually drank when the marathon ended with a bag of seventeen records, even though they didn't include the target mark of twelve hours. As will have been gathered from an en passant reference, early in this story, to the 1914 French G. P. Vauxhalls, Luton's employment of "modern" features like dual overhead camshafts predated the 1922 T.T. cars by more than the thickness of a world war. In fact, although the 44 litre jobs fielded at Lyons in '14 were understandably inferior in specific output to the Sir Harrywagens, it is arguable that the former, in one important respect, more accurately foreshadowed the technical practices of the 'fifties than the Ricardo layout: a Pomeroy design, the 1914 engine measured 101 by 140 m.m., making the bore/stroke ratio, rather obviously, 1 to 1.4. This, of course, was strikingly "shorter" than the generality of pre-WWI racing engines, and entitles the designer's son to claim, as he does, that old man Pomeroy set the ball rolling in the direction of tubbier power-plants with a high crank-speed potential. The trend might in fact have been much accelerated, and Vauxhall would probably have been the instrument of its hastening, if L. H. Pomeroy hadn't quit his Luton berth and gone to work in the U.S. in 1919. At the time of his departure he was busy on the development of an intended successor to the L head 30/98, featuring a single overhead. camshaft driven by multiple eccentrics, a light alloy crankcase and precisely the same cylinder measurements as his 1914 G.P. engine. This opus, designated the H Type, never saw the light of day, being nobody's sweetheart but old Pom's. But if he'd stayed instead of going, the OE edition of "Britain's fastest production car" would likely never have materialised, and the course of Vauxhall's high speed history might have been different again.  Special bodies in a great variety of shapes were mounted on the 30/98s in their heyday. The version above is a long-tailed example.  Raymond Mays makes fastest time at a Shelsey Walsh Hillclimb in the early 1930s, at the wheel of his Villiers Supercharge. The history of this 300 bhp sprinter can be traced in the book "Split Seconds", Mays' autobiography on which Dennis Mays, writer of the article "The Gryphon Wears a Grin" (above) collaborated.

|

Reader Reviews page 0 of 0

There are currently 0 reviews to display.

Add Your Review

<>

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||