Project X

For many decades the

automobile paparazzi have earned a good living seeking out prototypes and sending their grainy and sometimes fuzzy pictures to the motoring magazines press. The prototype is an important part in the automotive cycle, as it comes at a point where the marketing people in the company have test marketed a mythical product. They do this with surveys, or more likely these days, select focus groups, who perhaps did not even know they were contributing towards the design of a new car.

Having reached certain conclusions, the product development group in the factory steps in. They are the middle men, the people who have to get this mass of information transformed into a design. To do this they throw profitability and unit sales to the sales forecasters, the exterior and interior dimensions to another group, the detailed specification of the car to a third group, performance and weight to a fourth, and so on, until everyone in the product group is working on Project 'X'.

It is at this stage that the model gets its prototype number or name. In the case of Rover, it was a 'P' number, in the case of Fiat a project number, (which is the number usually given to Fiat models like 126, 127, 128 etc) and in the case of Austin/Morris an ADO number. Every factory has, or had, a different method. By the time all this work has been done, the car's potential market, its basic specification and even its projected selling price has been decided, subject to review.

It is now the turn of engineering to make the drawings and the calculations work, and the stylists to begin their work. Most major manufacturers have their own styling studios equipped to produce prototypes to certain levels and in the initial stages these prototypes must be mock ups. Up to now, the work in progress has been internal development. By this time, the various heads of engineering, styling and marketing are preparing their arguments to be put before the board of directors. This board is made up of directors at all levels but, principally, its the bean counters (aka accountants) who have to make the final costing analysis, check the sums and visualise whether the company is going to profit from this particular car.

The Clay Model

To present the facts of such a car in purely paper terms, that is in scale drawings, is not enough: the car has to live, it has to have shape, in three dimensions. A director who is going to commit millions of dollars of development money wants to feel what they is buying. It is now that the first prototypes are made. There are two basic ways of doing this. One way is to make a clay model, full size, and the other to do it in plaster of paris. This model has to be as realistic as the artists and model makers can make it and be complete with detail which, in turn, brings in the design departments of component suppliers.

Carrozeria Coggiola of Turin

When rectangular headlamps were first used, the lamp manufacturers had to do their own mock-ups, and supply them to the manufacturers so that everyone could see the effect in proper perspective. A clay model can be made to look very realistic, but it has a dullness to it when painted, so some manufacturers use plaster of Paris which gives a very smooth finish and can even be used for first metal dies in a finished car. For this, a company will either build the model themselves or go to one of the coach-building firms specialising in models to produce one for them. One such firm is Carrozeria Coggiola of Turin which has a reputation in the industry for the quality of its models in plaster of Paris.

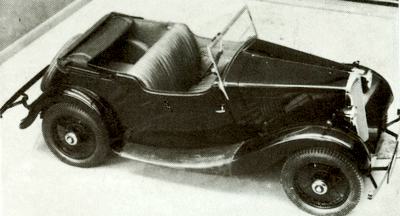

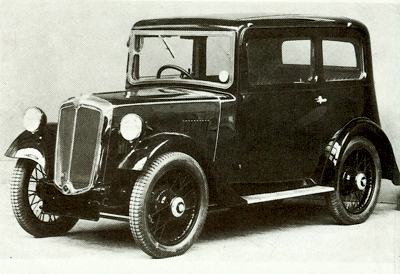

The Morris Eight tourer, used as a basis for an unsuccessful saloon prototype as seen below.

An unsuccessful prototype from the 1930s, in this case the Morris Eight.

Scale model of a Fiat 126.

A full size model of a Fiat 126. The designer is taking the measurements of the model.

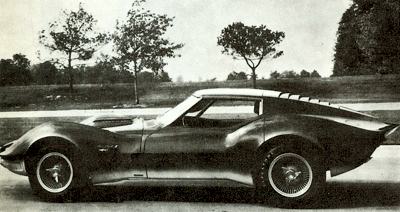

Protoype Chev Corvette, which was powered by a Wankel rotary engine.

Protoype Chev Corvette.

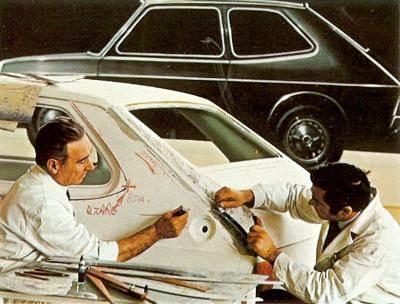

Designers re-shaping a prototype of the Fiat 127 with plaster.

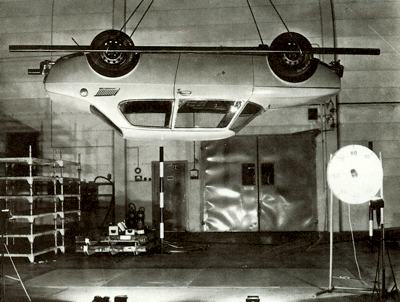

One of the final prototypes of the Saab 99, undergoing crash testing - before the drop.

One of the final prototypes of the Saab 99, undergoing crash testing - after the drop.

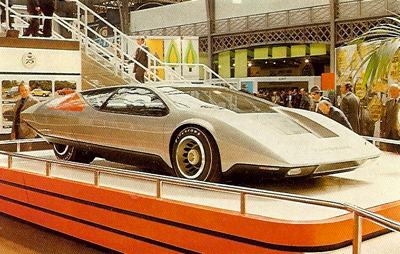

Vauxhall SRV prototype, which featured gullwing doors.

Chev Corvette Mako Shark II prototype. It featured adjustable stabilising fins and a slatted rear-window cover. The design was used to gauge the publics reaction. |

To make one of these plaster models, the model makers start with a light steel skeleton made of conduit covered with simple chicken wire. It is then plastered over like a doctor plastering a broken arm until the plaster is about 3 in thick. Throughout this process, the stylists and model makers may carve off bits which do not visually work and make modifications. At this stage, the prototype is fluid in design because it must be right when the day comes for the viewing. A finished prototype model, therefore, can go 70 per cent of the way to convincing a company board to go ahead or else give them the opportunity to make detail changes before giving the go ahead for the first full steel-bodied prototypes.

Raymond Loewy and the Studebaker Avanti

Sometimes, companies break the rules, a typical occasion being when Sherwood Egbert, President of the ailing

Studebaker Corporation approached industrial designer Raymond Loewy and demanded 'a sensational new car'. That was on 9 March

1961. Forty days later, a full-size mock-up was formally presented to Studebaker's. Board of Directors. To do it, Loewy and his team went into monastic hiding in the California desert and worked non-stop through all the early stages. Sketches and drawings were taped on to the walls, and in eight days the first 1/8th scale model was completed; although, in fact, it was only half a model, as the team mounted it in front of a mirror to get the total overall effect.

On 27 March, Loewy flew back to

Studebaker with his model under his arm and got the go-ahead, with certain modifications, to make a full-size clay model. Meanwhile,

Studebaker engineering were preparing full-size moulds for building mock-ups. When his revised mock-up was finished, Loewy telephoned Egbert and told him the model was ready and Egbert immediately flew out into the desert in a company aeroplane. He took half an hour to decide to give the project the go ahead, and in fifteen days a full-scale clay model, unpainted but chromed, was presented by Egbert to his fellow directors on the Studebaker Board. It was given the go ahead and, on 25 April

1962, just 363 days after that board meeting, the

Studebaker Avanti was introduced to the public as 'America's most advanced

automobile'.

Vauxhall Motors

One of the best-equipped styling and development centres in Britain was at Vauxhall Motors in Luton where all of the developments could be conducted under one roof and where there was even a display area on the roof of the building. A car could be rolled out of the specially constructed viewing room into the open to give everyone the chance of seeing the car in normal daylight conditions. Once given the 'green light', there were a number of plans to be finalised before an actual steel-bodied prototype could be made. There was the component prove-out side which would make exhaustive tests of the actual mechanical components of the new car, and the engineers then drew the new body panels and had replicas made in plastic so that they could work out in advance just how these panels would be stamped in the press shop. Mock-ups were made of the interiors, the seats and dashboard and rig testing of door locks and electrical items were carried out. Meanwhile, the first steel prototypes were built and sent out on to the roads.

While there are many exceptions to the rule, generally there is around a three-year time scale between the original idea and the final launch of the car, and in three years a company's sales graphs can change suddenly if there is a leak of a new model. It can cost a company millions and result in a speeded-up development programme which can be sometimes disastrous as the car is introduced before it has been fully tested. Back in the 1950s, Triumph showed a prototype car at the London Motor Show with a fat bulbous body, electric windows and various other items as a probe, just to test the market. The response was such that they then looked at the project seriously, but after a few prototypes had been built they discarded the idea as it was going to be too costly to put into production.

The Triumph TRio

In 1952, however, they tried again with a 2-litre sports car later called the TRio It was a much more down to earth and sensible design, made to be built in large numbers fairly easily, and contained various visual elements such as an external spare wheel inset into the short tail. Triumph's aim was to enter the American market with a new sports car, but this car was not quite right for the US market as it had very little boot space and, amongst other things, an antique chassis from an earlier Standard model. Between that motor show and the car's final introduction as the

Triumph TR2, the car was given a completely new chassis and the tail section was modified to provide a proper boot with the spare wheel tucked away inside.

In Triumph's case, they were not competing with themselves, they had nothing to lose by showing a prototype to the public at large. Indeed, by whetting the public's appetite they might even be accused of holding up sales of competitors' cars, so a prototype which is leaked can have a positive effect on a company provided the car is not going to clash with an existing model. The mass producer in the family-car field has much more to lose. The whole economics of the car industry are so precarious that an existing model may be targeted for a production run of x number of units per day, but if the rate of sales cannot keep up with numbers rolling off the assembly line, the car quickly becomes uneconomic over its whole life span.

A strong set of rumours backed up by photographs of a prototype can cause a trauma which is why the whole business of prototype testing is a very serious matter treated as such. In past years and before World War 2, there were few problems. Motor cars could roam about some of the more remote areas of America and Europe far from the prying eyes of the public. The testers themselves had their own favourites, and the classic Passes such as the Gavia and the Stelvio were used to check performance as well as handling. After the war, however, it was just about impossible because of the number of cars on the road, and this drove the manufacturers into more and more remote areas. The Europeans for a time decided to test in such remote places as Rovaniemi in Northern Finland, as well as North Africa and even Patagonia.

When you see photos published in the newspaper or motoring magazine of a well (or not so well) disguised prototype, this is indicative that the car is very close to being finally be produced. By now, the dies are being made for the body panels, the components have been ordered and the space on the production line has been allocated. In other words, the company is committed. In today's fast-moving society where delay can be enormously costly, the pressure is on the prototype department to complete their testing as quickly as possible. There are occasions, however, when this is not so.

The Rover Tallago / Rover 2000

There is the story about the development of the Rover 2000 which was notoriously long in the prototype stage. The original prototype body, for instance, was neatly disguised in Rover's gas-turbine car of the late 1950s which was being demonstrated as a possible new motive force in the industry. It was, at the same time, involved in the proving of the body and chassis for the P6 (The Rover 2000). The original P6 prototypes were actually on the roads in 1959, but the car was to change in shape radically before it was introduced five years later in

1964. The story, however, concerns the occasion when one of the last prototypes was allegedly involved in a crash and the police had to obtain details about the car. It is said that one of the managers in the company had rushed into the office of a senior executive at Rover and told him that one of the test drivers had been caught by the police in a P6 prototype.

The test driver was charged with not having his three-year test certificate; an ironic reference to the time Rover had taken over their prototype testing. That same car was tested extensively in Spain, and, to keep people off the scent, Rover had some chrome script made up with the name Tallago which was mounted on the car. Many of the continental papers used pictures of the Tallago hinting at what it might be; Tallago in Spanish, however, means scrap. Funny, but not as bad as the Mitsubishi Pajero, which in Spanish means Tosser or Wanker.

The role of the press in this whole masquerade is a vital one, and here there are two lines of opinion. One camp argues that everyone should know what the motor manufacturers have up their sleeves and therefore any sneak shots of cars in prototype form should be published. One of the leading papers to profit from this was the French magazine L' Auto Journal which established its reputation by revealing, to the embarrassment of many manufacturers, full-colour drawings and pictures of prototypes than the companies were trying to hide. It is difficult to blame a motor magazine for doing this because it is news and it does sell more copies, but the bulk of magazines and newspapers take the opposite view, seeing the damage that this can do to popular models and at the same time acknowledging that their advertising revenue would probably suffer at the hands of the dealers selling existing cars who might find themselves left with them on their hands.

Generally speaking, the photographs published show the models at a fairly late stage in development and within five or six months of launch: the critical period for sales when manufacturers are offering incentives to their dealers to sell off the existing stocks. At this stage in the game, the manufacturer can run his prototype and hope that nobody notices or else he can cover it up with brown paper and cardboard at the front and rear but, if anything, this draws more attention to the car. A decade ago a person had to know their cars very well to spot a new model on the highway and even then they would only have a fleeting glimpse - but these days with the proliferation of digital camera's (or those found on the mobile phone) it seems everyone has the opportunity to turn into an automotive sleuth.

There are occasions when real damage is done when photos are released, such as in the case of Peugeot who were forced to put a new car on view at a motor show well in advance of its planned launch date, because so many rumours and prototype pictures had been published, so much so that the company's existing model sales had taken a downward plunge. By introducing the car at the show and demonstrating that it in no way competed with the existing model sales of that model picked up again. The car was the Peugeot 604.

The Holden GTR-X and Hurricane

While there was probably never much opportunity to spot a prototype on Australian roads prior to the war, things changed when local manufacturing was set up by the big three, Holden, Ford and Chrysler. During the 1960s and 1970s the allure of the new model would well staged, with secrecy the key to building anticipation. Prior to launch, it was common for the new models to be rolled into the showrooms around the country, only to have a sheet covering them so that the only thing you really knew was that a new model was soon to be seen. Along with the traditional family sedans, there were other prototypes that made it to full road-going versions, but never went into production. Arguably the most noteable, and most lamented, is the

Holden GTR-X.

It very nearly became a reality, as is evidenced by the sales blurb... ""Engineers dream. Sometimes those dreams become

a reality. But not often. Few companies are able to

provide the technology, the facilities, and the manpower

needed to make dreams come true. One such dream is

the Holden Torana GTR-X. And it has come true. It is

the product of the

GMH Research and Development, and

Advanced Styling Groups. It was built to assess public

reaction to an advanced design two-seater sports car.

The GTR-X borrows heavily in styling and innovation

from

GMH 's experimental

"Hurricane", but it is designed with the

thought of possible limited volume production. And

low tooling costs could make it available for far less

than its European counterparts".

Along with the GTR-X, another noteable Holden prototype from the 1960s was the

Hurricane, although from the get-go this was seen by Holden as an experimental research vehicle, allowing them

"‘to

study design trends, propulsion systems and other long

range developments". There were some Ford's that were still-born too, and to this day leave us salivating. Imagine their value today if the

XA GTHO Phase

IV had actually made production (although 259

XA RPO83s were manufactured) and how about an

XT GT Coupe - which was actually shown at the

1968 Melbourne Motor Show.