WILLIAM RICHARD MORRIS, who became the first Viscount Nuffield, was a short, stocky, chain-smoking hypochondriac who made a vast fortune out of motor-car manufacture, and gave nearly £30 million of it to charitable trusts.

He was born in 1877, in a small terraced house in Corner Gardens, Worcester, the son of a wayward character who flitted from job to job, and who had even been a stagecoach driver in North America before his son's birth.

During his stay in America, William's father had also lived with a tribe of Red Indians for some time and had been adopted as a full member of the tribe. By the time young William was old enough to go to school, the family had moved yet again, to a house in James Street, Cowley, then a small village on the outskirts of Oxford.

William Morris was educated at the St James Church of England School in Cowley, and began work at the age of 15 in the shop of an Oxford cycle agent named Parker. The foreman, Dupper, was supposed to teach the boy the trade; young Morris was evidently a fast learner, and within nine months he was demanding a wage rise of sixpence a week on top of the four shillings he was already earning.

Parker turned the claim down, and Morris resigned to set up in business on his own, repairing cycles in his father's garden shed. From there it was only a short step to the manufacture of complete machines from bought-in components, and Morris received his first order from the local vicar, a tall man who demanded a larger-than-usual mount with a 28-inch frame to suit his unusually large body.

Champion of Oxfordshire, Berkshire and Buckinghamshire

The successful completion of this commission brought Morris further orders, but the fledgling cycle manufacturer didn't just rely on word-of-mouth publicity for his products: he also raced them, to such good effect that at one time he was champion of three counties - Oxfordshire, Berkshire and Buckinghamshire - over distances ranging from one to fifty miles.

However, he wasn't infallible, as F. G. Hunt (the mechanic who in 1913 built the first Aston Martin) recalled nearly three-quarters of a century later: 'In the 1897 Diamond Jubilee Year...Bill Morris had a little cycle shop in Oxford. During the celebrations, Colonel Palmer, of the famous (at least in the UK) Huntley & Palmers biscuit company of Reading, allowed a cycle race on his land.

Bill Caldicott, the Fairford postmaster's son, said to me: "Thee knows how to ride a bike, Frank - why don't thee go in for the race? So I enters, riding an old Star with dropped handlebars – the heaviest machine of the lot! It was on inch-and-a-half Warwick road

tyres while the other riders were using proper path-racing tyres. There was Bill Morris and a pal of his, a chap named Mitchell from Oxford and Arthur Griffiths, champion of the NCU at that time ... 'My mother breaks two eggs into a glass with a decent drop 0' brandy. "'Ere, me boy," her says, "that'll stay thee wind!" 'Of course, they all shoots away from me at the start, but sure enough I gets me second wind and catches them up. Morris and his pal were lying third and fourth - but I slips between them and comes in third!'

But minor setbacks like this didn't impede the teenaged Morris's progress. He had originally used his father's front parlour and garden to display his bicycles; soon he was successful enough to rent a shop at 48 High Street, Oxford, as well as repair premises in Queens Lane. Morris built himself a motor bicycle in 1901, machining the engine from proprietary components (though like most of its contemporaries it was doubtless a pirated de Dion Bouton design) and thought that this type of machine had sufficient sales potential to warrant quantity production.

The Oxford Automobile and Cycle Agency Limited

However, he lacked the capital for such a venture, and was forced to go into partnership with a local cycle dealer named joseph Cooper. They built a couple of motor cycles in 1902 before Cooper had cold feet over this rash scheme and backed out of the partnership. Morris was forced to cast about for other backers, and before long was one of three partners in the 'Oxford Automobile and Cycle Agency Limited', which boasted premises at 16 George Street, Oxford, as well as Morris's leasehold shop in the High Street.

At the November 1903 Stanley Cycle & Motor Show in the Royal Agricultural Hall, Islington, the company showed four Morris motor cycles. One was a belt-driven machine fitted with a 2¾ hp MMC

air-cooled engine while the other three were chain-driven. Two of these were bicycles, one with a 3½ hp de Dion water-cooled power unit and one with a 2¾ hp

air-cooled de Dion, while the third was a 2¾ hp de-Dion-powered tricycle fitted with a fore-carriage.

The company had also moved into the motor car business, and were offering 'the Speedwell Light Motor Car, two seats, fitted with de Dion engine of 6 hp, gear drive'. Speedwell were also UK agents for the Serpoliet Steam Car, which was also marketed by the Morris company. But while Morris was working fourteen hours a day in the garage, one of his partners, an undergraduate, was burning up the company's profits with a combination of extravagant entertaining and over-generous discounts and the Oxford Motor Agency was soon bankrupt.

Morris had to borrow £50 and stand in the pouring rain at the auction where the partnership's assets were sold off to buy back his own tool kit, which had been seized to help payoff the debts. On his own again, he retained the High Street shop, plus converted livery stables in Longwall, where there were a few machine tools downstairs, and an office upstairs where Morris's old father kept the accounts. This time, the business was a success, and in 1908 Morris disposed of the cycle agency, the High Street lease and the design rights of the motor cycle, to a friend named Armstead.

As well as operating a taxi and hire-car service, Morris had replaced the antiquated tram service in Oxford with a considerable fleet of 'ugly red motor-buses', and was agent for Arrol-Johnston, Belsize, Humber, Hupmobile, Singer, Standard, and Wolseley cars; for a time he retained a couple of motor-cycle agencies. By 1910 he had sufficient capital for expansion: the Longwall premises were torn down and completely rebuilt in best Edwardian Classic style, earning the local nickname 'The Oxford Motor Palace'. In addition, further premises were acquired in 1910 at Cross Street and in 1913 in the old 'Queen's Hotel. William Morris was now in a position to realise a long-standing ambition - to become a motor manufacturer.

He planned to manufacture a quality light car, to sell at a modest price; but he would assemble it from the best proprietary engine, gearbox and chassis components available. In that way, he would be able to produce in quantity without spending any of his precious capital on development or tooling. Additionally, the use of components made by companies who were acknowledged experts in their fields would guarantee a reliable end product.

This photo, dated 1895, shows William Richard Morris at the age of 18. Six years after the photo was taken, he would build a motorised cycle and begin the legend of Morris.

This photo, dated 1895, shows William Richard Morris at the age of 18. Six years after the photo was taken, he would build a motorised cycle and begin the legend of Morris.

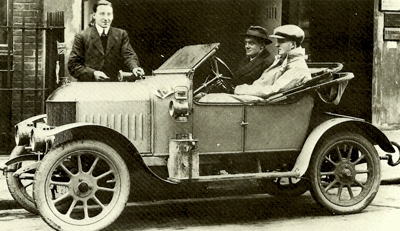

The two-seater 1913 Morris Oxford runabout. It was popular with the press and public alike, in spite of limited seating.

The two-seater 1913 Morris Oxford runabout. It was popular with the press and public alike, in spite of limited seating.

A fleet of 1913 Morris Oxfords stands ready for inspection prior to delivery.

A fleet of 1913 Morris Oxfords stands ready for inspection prior to delivery.

Following the Oxford was the Morris Cowley, introduced in 1915. It was fitted with a 1548cc four cylinder engine.

Following the Oxford was the Morris Cowley, introduced in 1915. It was fitted with a 1548cc four cylinder engine.

A photograph of an unknown British family, with dad behind the wheel of his new Morris Cowley.

A photograph of an unknown British family, with dad behind the wheel of his new Morris Cowley.

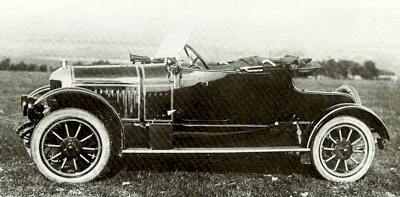

1922 Morris Cowley sports, fitted with two-seater boat-tail coachwork by Compton and Hermon Ltd.

1922 Morris Cowley sports, fitted with two-seater boat-tail coachwork by Compton and Hermon Ltd.

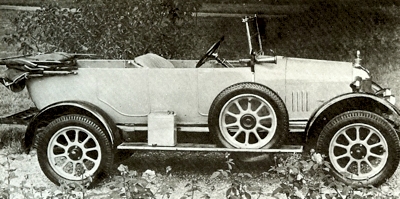

1923 Morris Cowley open Tourer.

1923 Morris Cowley open Tourer.

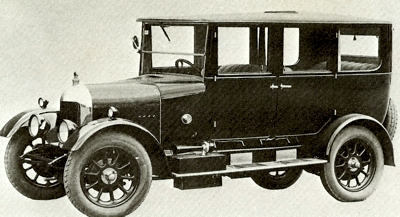

1923 Morris Cowley four-door.

1923 Morris Cowley four-door.

1926 Morris Oxford Tourer. By this time, the side valve engine had grown in capacity to 1802cc

1926 Morris Oxford Tourer. By this time, the side valve engine had grown in capacity to 1802cc.

A 1928 Morris Cowley, after the transition to the more efficient (and cheaper to manufacture) flat radiator

A 1928 Morris Cowley, after the transition to the more efficient (and cheaper to manufacture) flat radiator.

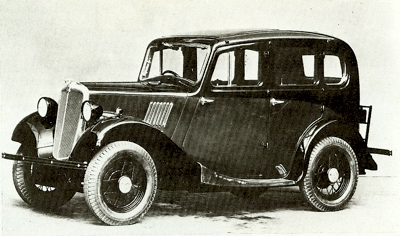

1935 Morris 8 Sedan, powered by a 918cc four-cylinder

1935 Morris 8 Sedan, powered by a 918cc four-cylinder.

1938 Morris 8 Tourer, which had a top speed of 60 mph - which was considerable for the time.

1938 Morris 8 Tourer, which had a top speed of 60 mph - which was considerable for the time.

1938 Morris 8 Series II four-door sedan.

1938 Morris 8 Series II four-door sedan.

The Morris Six series MS Sedan, manufactured from 1948 to 1954. It was powered by a 2215cc six cylinder engine.

The Morris Six series MS Sedan, manufactured from 1948 to 1954. It was powered by a 2215cc six cylinder engine.

1949 Morris 10 cwt station wagon.

1949 Morris 10 cwt station wagon.

The Cowley name was revived in 1954 for their mid-sized model. The "new" Cowley was powered by a 1200cc engine, which was increased in 1956 to 1489cc.

The Cowley name was revived in 1954 for their mid-sized model. The "new" Cowley was powered by a 1200cc engine, which was increased in 1956 to 1489cc.

Instantly recognisable, one of the most famous models was the Morris Minor 1000.

Instantly recognisable, one of the most famous models was the Morris Minor 1000.

The Mini Minor was introduced in 1959.

The Mini Minor was introduced in 1959.

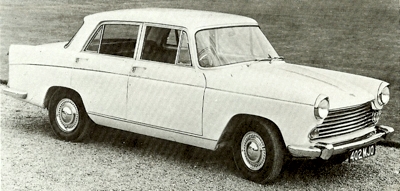

The 1967 Morris Oxford.

The 1967 Morris Oxford.

1962 Morris 1100.

1962 Morris 1100.

Morris 18-22 series model, introduced in 1975. It was powered by either an 1800cc B series or 2200cc E series engine.

Morris 18-22 series model, introduced in 1975. It was powered by either an 1800cc B series or 2200cc E series engine.

This photo was taken in 1962, and shows Lord Nuffield, then 85, standing next to a Morris 1100.

This photo was taken in 1962, and shows Lord Nuffield, then 85, standing next to a Morris 1100. |

Lord Macclesfield

He had begun investigating the supply of components in 1910, but found that he would need additional s capital; in 1911 William Morris once again plunged into partnership. This time, however, he had found the ideal backer, Lord Macclesfield, a wealthy motor enthusiast who was prepared to invest some £25,000 in 3 Morris's proposed manufacturing venture,. without s interfering too much in how the company was run. In August 1912, WRM Motors Limited was founded, with Macclesfield as President and Morris as Managing Director.

Morris had already contracted for the supply of components for his new car: the engine/gearbox units would be supplied by White & Poppe Ltd, a Coventry-based partnership between a British and a Norwegian engineer, E. G. Wrigley & Company would provide the worm-drive rear axles as well as the front axles and

steering mechanism, while a local coachbuilder, Raworth, would supply the bodies. For his factory, Morris had acquired the former Military Training College at Temple Cowley, once the grammar school where Mr Morris senior had been educated. It wasn't sentiment which prompted his son to take over the building, however, but the low price at which it was available, the result of its having stood empty for twenty years.

The Wooden Engine

Though Morris now had a motor works, he was unable to produce Cars, for White & Poppe had failed to produce engines on time. Apparently Willans & Robinson of Rugby, who were supplying the castings for this power unit, had supplied the first set at half the correct size, due to a dimensioning error in the White & Poppe drawing office. The delay meant that Morris couldn't exhibit at the November 1912 Motor Show at Olympia as he had planned, but he didn't waste his railway ticket, instead taking a set of blueprints up to London, and on the strength of these persuaded Gordon Stewart, of the London motor agents Stewart & Ardern, to place an order for 400 Morris-Oxfords rather than the Marshall-Arter cyclecars that he planned to buy. Stewart was the active member of Stewart & Ardern-Ardern being very much a sleeping partner, a shadowy figure that few people connected with the company could ever recall having seen.

Following the Motor Show fiasco, the car's first public appearance was scheduled to be the North of England Motor Show at the Exhibition Buildings, Rusholme, Manchester, held from 14th to the 22nd February 1913, where the catalogue promised the presence of a chassis and a complete Morris Oxford two-seater. The two-seater did appear: but it wasn't quite what it claimed to be, the cylinder blocks still hadn't come through, and the engine was a wooden dummy!

The first roadworthy Morris Oxford wasn't ready for Stewart to collect until the end of March 1913. He drove off confidently, only to come to a halt in the midst of mechanical chaos a few yards further on with a shattered universal joint in the transmission. Poppe had specified that this joint should be made of cast iron for durability, but his factory had used an inferior grade of iron which shattered under stress. After Stewart had again come to grief with a second universal failure on the road to London, Morris demanded that all universals .should henceforth be cast from bronze instead of the naturally brittle iron.

There was another major drawback to the Morris Oxford that was not realised by either Morris or Stewart: they were both little men, who assumed that as the standard two-seater body would take the pair of them without discomfort, it would be spacious enough for anyone. In fact, even for a couple of normal stature, the Morris Oxford was distinctly tight under the armpits, and for a tall driver it was almost impossible to carry a passenger as well. The motoring press, however, took kindly to the little car, which was one of the liveliest in its class.

The Cyclecar found that its 1018 cc engine could endow 38 mph in second gear - equivalent to a dizzy 3800 rpm - and that top speed was around 55 mph. At that speed, however, the lightness of the car proved a handicap, as the suspension took over, and the little Morris bounded along the road and became virtually uncontrollable. The price of such performance was a touch of temperament, and though the engine was generally willing and lively, it was very particular about spark plugs, only running reliably on German Bosch units. And it tended to run very hot.

It must have been an equally soggy journalist who wrote in “The Cyclecar” that the car's hood 'served to keep off the major portion of the rain'! But such minor failings couldn't conceal that the Morris Oxford was, at £175, remarkably good value, and, during the first nine months of production (March to December 1913) output totalled 393 cars; the following year, this figure soared to 909. This happy state of affairs, however, was to be quickly upset by the outbreak of war, and production was curtailed so that the Cowley factory could be devoted to the production of munitions.

Morris lobbied the corridors of power in Whitehall so effectively that he received contract after contract for supplying the Navy with mine-sinkers. Morris Oxford production was progressively cut back; only 180 were built in 1915, 13 in 1916 and one in 1917, assembled from parts produced before the war. In any case, the Morris Oxford had already served its purpose by proving to Morris that he could be a success as a car manufacturer.

Now he planned to challenge the giants of the motor industry on their own terms. He realised that a lively two-seater like the Morris Oxford was limited in its appeal, and that the future lay with the low-cost, reliable, family four-seater, a type which was at that period almost exclusively the province of American manufacturers. Morris had already projected a four-seater version of the Morris Oxford in 1913, only to find that it would be prohibitively expensive to build. He therefore determined to find out for himself how the Americans could manage to produce four-seaters so cheaply, and, accompanied by Hans Landstad, the chief draughtsman of White & Poppe, he spent a month in the United States at the end of 1913.

This fact-finding trip proved invaluable: Morris was also to obtain quotes from a number of American component suppliers which proved to him that it would be cheaper to buy parts in America and have them shipped across the Atlantic than to obtain them from English manufacturers. He asked White & Pop pe to quote for a 1500 cc engine/gearbox unit for the car he was planning, but they couldn't bring the cost down under £50, which was virtually twice what the Continental Motor Manufacturing Company of Detroit was asking.

His new-found role as a manufacturer of munitions didn't prevent Morris returning to the United States on 18 August 1914, again accompanied by Landstad. Even then, the design of the new car hadn't been finalised, Morris and the seasick Landstad using the voyage to lay down the outline of a four-seater car designed round the American components for which they had received quotes after their previous visit. Despite the outbreak of war, Morris contracted for 3000 engine/gearbox units from Continental, and then returned home, while Landstad stayed on to gain first-hand experience of American mass-production methods, working with Continental by day, finalising the design of the new Morris at night and spending what time remained visiting other motor manufacturers including, inevitably, Ford, where he obviously learned a great deal.

Once the first Continental Red Seal engine intended for the new Morris was running successfully, Landstad returned home to Coventry. But it was little surprise that he joined WRM Motors soon afterwards, about the time that development of the new model began. By April 1915 the

prototype was running. It was called the Cowley, and in two-seater form it undercut the cheapest Oxford: cost was 158 guineas against £168, a small difference that seemed the larger when one car was compared with the other.

The Cowley could carry a genuine four-seater body, and had an engine of 1495 cc. Furthermore, its design was far more up-to-date, the engine featuring such Yankee conceits as a detachable

cylinder head and a dipstick; dynamo lighting replaced the oil/acetylene system of the Oxford and the rear axle had helical gearing for quiet running. But an even greater advantage of the new model was that supplies of components were assured (until the German U-Boats became a menace) at a time when the British components makers were devoting their factories to war work.

Maybe Morris saw his factory's output of mine-sinkers as insurance against loss of components: even so, half the 3000 Continental engines shipped over during the war were sent to the bottom of the Atlantic by the enemy nevertheless, Morris was able to maintain production of the Cowley throughout the war, while most of his contemporaries were forced to cease assembly around 1916. Peak year of the Continental-engined Cowley was 1916; 684 were sold, against 161 in the last three months of 1915, 125 during the whole of 1917 and 198 in 1918.

In 1919 281 Cowleys were produced; but the following year just one Continental Cowley left the works. Two unforeseen events had combined to upset Morris's carefully laid plans to dominate the United Kingdom market with Cowleys built from American components: firstly, in September 1915, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Reginald McKenna, imposed a duty of 33.3 per cent on imported cars and accessories, which meant that the price of the cheapest Cowley rose to 185 guineas just as the model became generally available.

And then, in March 1916, the Government placed a total ban on the importation of American cars or parts (except those used to manufacture commercial vehicles). Hardly surprisingly, Morris added a delivery van to the Cowley range in November 1916. A fresh problem came with the Armistice and the lifting of the ban on American imports, and the Continental Motor Company decided that there wasn't enough demand to warrant resuming production of the 1496 cc engine used in the Cowley. So Morris, limping along on what remained of his war-time stock of parts, had to cast about for British suppliers once again.

White & Poppe were unwilling to co-operate, the Dorman Engine Company inconveniently wanted a £40,000 deposit as evidence of good faith, and the New Pick Motor Company of Stamford, Lincolnshire, had insufficient production capacity. But now that the dogs of war had ceased barking, the munitions factory set up at the beginning of hostilities by French motor and armament company, Hotchkiss & Cie in Coventry was sadly unemployed. Their works manager, H. M. Ainsworth, had plenty of pre-war experience in the company's car plant at St-Denis and lost no time in calling his directors over from France for a conference with Morris.

It was agreed that Hotchkiss would produce an engine to Morris's specification, would hopefully be able to reach Morris's price target as production rose, and would not need a deposit on the order. By September 1919 the Hotchkiss engine, a pretty faithful copy of the Continental Red Seal, to which Morris had acquired the design rights, was being fitted into cars, and manufacture, which had slowed almost to a standstill, began to gather momentum: from 5 in September 1919, it rose to 10 the next month and to 35 in November.

However, the component shortages meant that Morris had missed out on the post-war car sales boom. And just as the Cowley factory had got back into its stride in 1920, disturbing reports came from America of a sudden and vicious recession in car sales-even Ford had had to close down his factory temporarily. By the end of the year, the slump had hit Britain. Morris sales plummeted from 276 in September 1920 to 92 in December and 68 the following month.

As the old WRM Motors company had been dissolved in mid 1919 and a new company, Morris Motors Limited, formed with a nominal capital of £150,000 to exploit the anticipated vastly increased Morris sales to the maximum by getting rid of the old North of England and South of England agents and appointing a new dealer force, the drop in sales was particularly embarrassing to William Morris. You can almost imagine Morris sitting in the old headmaster's room in the Cowley factory which was his office for nearly half a century, belching with the stomach wind which perpetually bothered him, and perhaps sipping on a glass of Sanatogen or bicarbonate of soda - his two panaceas - to try to quell his internal disquiet.

How to get sales moving once again? The idea, when it came to him, wasn't original, but it had already worked for Henry Ford. And the key to it was that newly appointed network of agents. He would cut the prices of his cars - and the agents' profit margins - in an attempt to clear his unsold stocks and maintain production. The most popular model, the Cowley four-seater, was reduced by the greatest amount, £100, from £525 to £425; the two-seater shed £90, bringing the price to £375.

In late 1919 the Oxford name had been revived for a de-luxe version of the Cowley: the Oxfords now lost £25 from their purchase price, which became £510 for the two-seater and £565 for the four-seater, while the more sybaritic coupe was now £80 cheaper at £595. It was a good scheme, and a similar venture had saved Ford; but the British firm of

Bean had already tried it with a total lack of success. Morris, however, had timed his reductions impeccably: sales rose to 244 in February, 377 in March, and showed a total of 3077 for the year, compared with 1932 models sold in 1920.

Even Morris was taken aback at the success of the price cuts: their effectiveness was measured in increased profits, and Morris suddenly became a major force in the British motor industry. Other manufacturers belatedly followed his lead at the Motor Show and cut prices by an average of 17 per cent - but Morris reduced his prices even more. The four-seater Cowley dropped from £375 to £299, the four-seater Oxford from £425 to £341. In the space of nine months, the price of the former model had been cut by 35 per cent and that of the latter by 21 per cent.

Helped Along by the 1920 British Road Traffic Act

Paradoxically, the increased motor taxation imposed by the 1920 Road Traffic Act was another beneficial factor in the Morris success story. In 1920, Ford had over 40 per cent of the British market: but the new Act charged the motorist £1 per horsepower (RAC rating) instead of the maximum of £6 6s that had previously prevailed, and the Ford was now taxed at £22 annually. The Morris cost £150 more than the Ford to buy, but its annual tax was only £12; and to the parsimonious mind of the average motorist this annual saving was more important than the cheaper first cost of the Ford, and before long the Morris Cowley was challenging the Model T on the home market.

The 1922 season was doubly successful: a total of 6937 cars was sold, while Morris reduced his selling prices still further, to the point where they seriously embarrassed his less affluent rivals, many of whom went under in their efforts to compete. Now Morris decided to play the autocrat: and the first result of this policy was a parting of the ways between Morris and the man who had originally provided his financial backing, Lord Macclesfield.

Removing Macclesfield

With £25,000 invested in the company, Macclesfield was naturally interested in how it was being run, and was quite likely to make unannounced visits to Cowley and wander round the production lines chatting to the workmen; he also annoyed Morris by asking questions about company policy at board meetings. These were curious affairs, as Morris was not very good at conventional ways of doing business, and conducted the meetings with a grasshopper inconsistency which his naturally inarticulate manner did little to alleviate.

Morris resented what he regarded as Macclesfield's interference in the way he ran his company, and decided to buy him out; the peer was surprised to receive a cheque representing the face value of his shareholdings, which had a far greater potential worth, but took the hint gracefully and severed his connection with the firm for £25,000. Now William Morris was in sole command, and aiming to create a completely self-sufficient car-producing empire which, like that of his American exemplar, Henry Ford, would have no need to rely on outside suppliers.

The Aquisitions Begin

Already several companies were almost entirely dependent on Morris business for their continued survival, and it followed with logical inevitability that William Morris should take them over. One by one he acquired Osberton Radiators Limited, Hollick & Pratt, the bodybuilders (whose factory had just burned down, and whose director, Lancelot Pratt, became Morris's second-in-command, but died aged 44 in 1924), and-the biggest coup of all - the Hotchkiss factory at Coventry. Hotchkiss fought hard to maintain their independence, but Morris eventually overcame their resistance with an offer of almost £350,000 for their share capital, and Ainsworth departed for the main Hotchkiss factory at St-Denis, where he remained in charge of car production until the Germans marched into France.

The Hotchkiss works became Morris Engines Limited, and output soared as the factory's unrealised potential was exploited. The ailing Wrigley company was also acquired - it later became Morris Commercial Cars - and Morris managed to obtain extended credit from Dunlop, who supplied all his tyres, and

Lucas, who provided all the electrical equipment. As he had asked his bank for twice as much credit as he needed, and as he insisted on cash payment for all cars before they left the factory, William Morris was in the happy position of running his factory on the money of those who depended upon his products for their livelihood.

Exit Edward Armstead, Enter Cecil Kimber

He was also still in the garage business, but since 1919 had entrusted the running of the Morris Garages to a general manager, Edward Armstead, the friend who had bought the design rights to the motor cycle in 1908. Three years later, Armstead gassed himself in mysterious circumstances, and his sales manager,

Cecil Kimber, took over. Hence, shortly afterwards, the first MGs .... Morris was empire-building almost by instinct, and occasionally he over-reached himself. He bought a coal forest from one of the Free Miners of the Forest of Dean in the fond hope of supplying his factories' needs to fire the furnaces and provide heating.

But the mine-workings were flooded, and the scheme came to nothing. So, too, did his acquisition, in December 1924, of the Leon Bollee factory at Le Mans. This attempt to produce a car for the French masses resulted in a loss of £150,000 in four years and several unsaleable models before production was stopped in 1928. Another fiasco was Morris's attempt to build a car for the colonies, where American makes had long been dominant.

The Empire Oxford

The Empire Oxford was built by Morris's truck factory, Morris Commercial Cars Limited, and had a 15.9 hp engine coupled to a four-speed gearbox. It seemed a well built car in the best Morris tradition - but it just didn't sell. Those that were shipped to Australia were soon to be sent back to Cowley in disgust! This must have been a bitter rebuff to Morris, who had a great liking for Australia, and was already cultivating the habit of taking a cruise to Australia each year.

However, on the home market, Morris had little cause for complaint. His 'bullnosed' Cowleys and Oxfords were selling in phenomenal numbers, with sales soaring from 6,937 in 1922 to 20,024 in 1923, to 32,939 in 1924, and peaking at 54,151 in I925, the last full year that the old model was produced. The Bullnose, which was produced in 11.9 hp form as the Cowley (and Oxford pre 1924) and as the 13.9 hp Oxford from 1923 on, had a certain homely charm, plus some distinctive features like its permanently engaged Lucas Dynamotor, which combined lighting and starting functions, giving the side effect of uncannily silent engine starting without the whir and clash of the Bendix pinion.

This, however, was completely nullified by the Bullnose's three-speed gearbox, on which first emitted a mellow moan and second an agonised shriek like a buzz-saw ripping through timber which could be heard for half a mile on a still day. At the end of 1926, the restless tide of progress claimed the Bullnose, and a new model appeared, with a fashionably square-cut

radiator which was claimed to give 60 per cent greater cooling capacity than the older pattern (which was, coincidentally, more expensive to produce). The new model was the result of a visit to America by William Morris in September 1925.

The Pressed Steel Company

The fact that while there he had turned down an offer of £11 million for Morris Motors was irrelevant: what mattered was that he had met Edward G. Budd of Philadelphia and his fast-talking vice-president in charge of sales, Hugh Leander Adams. They had given Morris the full hospitality treatment, and convinced him of the merits of the Budd all-metal body construction, with the result that Morris Motors joined with the Budd Company in setting up a factory in England to produce Budd bodies under licence: it was named the Pressed Steel Company.

With this novel form of body construction (which was not the first all-metal coachbuilding to be seen in England, however) fitted on a redesigned chassis of greater torsional rigidity, Morris seemed to have the answer to the problems of producing bodies in vast quantity to match his production of chassis. But there were many teething problems, not least of which was the total inexperience of the Pressed Steel Company. The dies were untried, and the methods of working totally alien to the workforce.

When the first all-steel bodies were fitted to Morris Oxford chassis, it was evident that the standards of finish were far below those of even the cheapest coach built bodies - and the dies were reputed to have cost £120,000 before a single panel had been produced! The panelling was wavy, door and window apertures were out of true and the windscreen leaked - 'It ought to be sold as an all-weather body,' remarked a director when the car was shown to the Morris management for the first time, 'it lets all the weather through ... '.

The problems were solved, but it took time. Morris was displaying all his characteristic worry signs, scratching the nape of his neck, sitting cross-legged and wagging his foot up and down ... and to cap it all he had contracted a painful bout of sciatica after slipping on the concrete floor of his garage, which acted as a sharp spur to his latent hypochondria, and encouraged him to contribute towards the extension of the Wingfield Orthopaedic Hospital.

Elizabeth Maud Anstey

It must have been a trying time for his wife, who was intensely jealous of his work - as well as being probably more parsimonious in small things than her husband. He had married quite late in life, and his wife, the former Elizabeth Maud Anstey, was a first-class cyclist- 'a jolly good powerhouse on the back of a tandem' was how one of Morris's executives irreverently described her. The couple's idea of a relaxing weekend was a tandem trip from Oxford to Aberystwyth and back, but when William Morris became too involved in his work, his wife retreated into her resentment of his work, and refused to have any children.

Consequently, as Morris grew older, so he began to lose interest in his empire, he had no heir to pass it down to, and he began to take refuge in his lengthy trips to Australia, leaving others to take the helm in his absence. His last great act of empire-building came in 1927 when, against determined bidding from Sir Herbert Austin, Morris bought the moribund Wolseley company, formerly part of Sir Basil Zaharoff's Vickers group, for £730,000.

Buying Out Wolseley

Wolseley had been ruined by an ill-conceived model called the 'Silent Six', but their name still carried an aura of prestige. Furthermore, the Wolseley acquisition also brought Morris an engine design which had the promise of greatness about it. This was the single-overhead- camshaft layout which Wolseley had cribbed from the Hispano-Suiza aero-engines they had built, reputedly without licence, during World War 1. Under Wolseley's aegis, however, this had proved a power unit of singular gutlessness, with its hidden reserves shown only by Sir Alastair Millar's Wolseley Moths at Brooklands.

This was the design of engine chosen to power the new light car which Morris was planning, though it first appeared on the 2½-litre Morris Six of 1928, which was developed into the 1930 Isis. News of the Morris light car appeared in a controlled leak in May 1928, prompting Morris's rival, Clyno, to bankrupt themselves in an attempt to produce a £100 version of their 9 hp Century model.

William Morris becomes Baron Nuffield

The 8 hp Morris Minor was introduced for the 1929 season, benefitting nicely from the move to smaller cars caused by the reintroduction of the petrol tax after a seven years hiatus. The first year's production of the new model totalled 12,500; altogether 39,000 overhead camshaft Minors were built before production ceased in 1932. In 1929, William Morris was created a baronet; in 1934 he became Baron Nuffield, taking his title from an Oxfordshire village.

Between those dates, his attitude to the company he had founded took a fundamental change. He had made history with the first full size £100 car, a side-valve Minor two-seater available only in grey with black

radiator and lamps. This was announced as the clock struck midnight at the Stewart & Ardern New Year's Party which celebrated the arrival of 1931, and, having achieved this qualified success (even though the car didn't sell particularly well); Nuffield gradually lost interest.

Leonard Lord and BMC

His trips to Australia became even more protracted, and he was content to leave the running of his company in the hands of delegates like Leonard Lord, who had come to Morris from Hotchkiss, and who had become one of Britain's leading authorities on mass production techniques - and a ruthless organiser. In 1936 Nuffield refused to give Lord a share in the profits - and Lord stormed out to join Austin, vowing that in the fullness of time he would be back to take Cowley apart 'brick by bloody brick'.

Which is almost precisely what happened when Sir Leonard Lord masterminded the formation of the British Motor Corporation in 1952, a shotgun wedding of almost incompatible partners. Nuffield's lack of interest was evident in the company's products during the 1930s; initially, these had a solidly traditional air, with only minimal nods in the direction of progress, such as the adoption of the 'Eddyfree' windscreen, big-hub wire wheels and fully-valanced mud wings (and, less successfully, direction indicators in the shape of the Wilcot Robot, midget traffic lights fixed to either side of the car, and so confusing in use that they were quietly junked at a loss of £50,000).

Then, in 1934, came the Minor's successor, the Morris Eight, whose styling was a blatant copy of the contemporary Model Y Ford - and which sold over 50,000 in nine months, 250,000 in its four-year life, before it was replaced by the streamlined Series six-cylinder E-series. Lord Nuffield had created a vast fortune for himself, as the shares were selling for around £2. In order to put his wealth beyond the reach of the taxman, Nuffield began endowing charities in earnest; by 1938 he had donated £ 11,500,000 to research, education and charity.

Sir Oswald Mosley's Fascist Movement

Over £3 million of this had gone to Oxford University (in spite of his long-seated mistrust for the students, who had always been slow settling their accounts in the cycle-building days, and his feud with the University authorities, who resented the encroachment of the Morris industrial empire on the City of Dreaming Spires): in 1937 he endowed Nuffield College, where post-graduate students could study social, economic and political problems. Hand-in-hand with this went his involvement with Sir Oswald Mosley's Fascist movement, for at that period Nuffield was a firm believer in government by benevolent dictatorship.

Despite his sympathies for the Blackshirts, he was created Viscount Nuffield in 1938. By now his role in the Nuffield Organisation was largely negative, as a bearer of destructive criticism, and his hypochondria was becoming an open embarrassment to his executives. Nuffield had convinced himself that he had diabetes, and had contracted the habit of giving himself urine tests in the office. A popular story we have found, and which we believe to be true, is that one day during the war, one of his directors took a £6 million Ministry of Supply contract to Nuffield for signature. The great man, glancing at the clock, apologised, crept into a corner of the room, and returned bearing a full test-tube, to which he added a pinch of copper sulphate, heating the noxious mixture over a spirit lamp. Unfortunately, the tube shattered, and the contract was deluged with Nuffield's sample.

After the war, Nuffield was instrumental in founding an Australian factory for the Nuffield Organisation in a second attempt to break into the Antipodean market with a purpose-built product. This venture eventually cost the British Motor Corporation a great deal of money, and was expensively shut down in 1974. When Nuffield died in 1963, it was as a philanthropist and not as a motor engineer that he was remembered. However, his memory of recent events had been clouded by his last illness, and, perhaps kindly, during his final months, Nuffield was living in spirit in the great days of the pre-1930 era.

British Leyland

In 1968, in further rationalisations of the British motor industry, BMC became part of the newly-formed

British Leyland Motor Corporation (BLMC), and subsequently, in 1975, the nationalised British Leyland Limited (BL). The Morris marque continued to be used until the early 1980s on cars such as the Morris Marina. The Morris Ital (essentially a facelifted Marina) was the last Morris-badged passenger car, with production ending in the summer of 1984. The last Morris of all was a van variant of the Austin Metro.

In the early 1980s, the former Morris plant at Cowley and its sister site the former Pressed Steel plant, were turned over to the production of Austin and Rover badged vehicles. They continued to be used by BL's Austin Rover Group and its successor the Rover Group, which was eventually bought by BMW, and then by a management consortium, leading to the creation of MG Rover. None of the former Morris buildings now exist, British Aerospace sold the site in 1992, it was then demolished and replaced with the Oxford Business Park.

The adjacent Pressed Steel Company site (now known as "Plant Oxford") is now owned and operated by BMW, who use it to assemble the new MINI. The rights to the Morris marque are currently owned by Nanjing Automobile (Group) Corporation. A sad end to one of the greatest British automotive marques of all time.

Further Reading: Morris Car Reviews