John Kemp Starley

Credit for the practical development and successful commercial promotion of the 'safety' bicycle goes without question to John Kemp Starley, of Coventry, whose 1888 design has been followed ever since and was the foundation of the lasting reputation of this ingenious engineer. J. K. Starley's use of the name Rover began in the mid 1880’s at a time when his little firm of Starley & Sutton was making a reputation with its 'Meteor' tricycles and other two or three-wheeled vehicles.

It spread gradually to subsequent productions of that concern, to those of its successor of 1889, J. K. Starley & Co., and, in turn, to those of its successor, The Rover Cycle Company Limited, of 1896. When the first Rover car appeared, in 1904, its name was one already known and respected internationally.

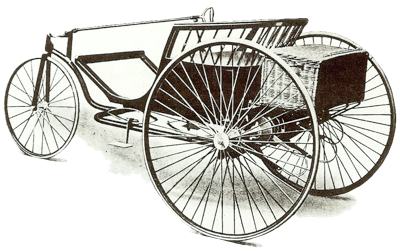

Before 1900 there had been two experiments with self-propelled road vehicles. The first of these, an electrically driven tricycle, built and tested by J. K. Starley in 1888, in England was illustrated and described in early Rover car catalogues, and the second, according to the motor-cycling historian, the late James Sheldon, was a De Dion engined Rover Bath Chair that appeared at a demonstration in the Old Deer Park, Richmond, in 1899.

Then, in 1903, a year or so after the death of J. K. Starley, Rover introduced its first motor-cycle designed by Edmund Lewis, at that time chief engineer of the Daimler Motor Company in Coventry. His original Imperial Rover had a 2½ hp vertical single-cylinder engine and, along with its successors and the single-cylinder, water-cooled tri-car of 1904, featured high standards of build and finish. It was considered to be a quiet machine.

The New 5 h.p. Rover Car

Towards the end of 1903 Lewis was officially invited to prepare designs for a Rover car and within months the first one was on the road; public appearances in competition followed, and in August and September, 1904, various motoring publications carried detailed descriptions of 'The New 5h.p. Rover Car'. Its outwardly conventional appearance disguised much that was unorthodox by the standards of the time - most notably a 'backbone' frame that carried the little vertical single-cylinder engine along with the clutch and gearbox and enclosed the propeller shaft.

The rear axle housing another substantial aluminium casting was secured at right angles to its after end. The front axle, with its single transverse spring, was fixed to a strong aluminium bracket bolted to the front of the crankcase, and the body framing-largely of cast aluminium also-rested at its rear on two long half-elliptic springs that were bolted to the ends of the axle casing. At the front it was carried by a swivel bar placed above the transverse spring. It was a simple yet unusual system that was easy to build with existing facilities despite the fact that Lewis - unlike so many contemporary designers - made no use at all of cycle building techniques.

The Rover Eight

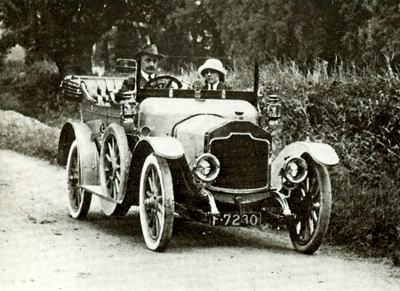

His Eight was comparatively light in weight yet amply strong - a point made in a most striking fashion by that insatiable traveller, R. L. Jefferson, towards the end of 1905. He drove an Eight from Coventry to Constantinople and the fact that his 2,500 mile journey took 10 days longer than the scheduled 5 weeks was due almost entirely to the appalling road conditions encountered and to multi-national bureaucratic delays. Apart from strengthened suspension and the provision of dual ignition the car was basically standard. The crankshaft and camshaft of the Eight's 1300 cc engine ran in ball bearings as did the main-shaft and counters haft of the gearbox and the half shafts. The

gear lever was mounted on the

steering column, below the wheel, and the change it controlled was not beyond contemporary criticism.

In its original form the Eight cost UK£200, weighed 10½ cwt and could reach 8, 16 and 24 mph respectively in its forward speeds. Its success was swift and in 1905 a second, even smaller model was introduced to take its share of another sector of the market. In its simplest and cheapest version the Six cost only 100 guineas but it was a thoroughly sound, reliable and economical little car. Apart from its unit-construction engine, clutch and transmission it was of more conventional design than the Eight. Its commercial success was also rapid. Subsequent Lewis-designed Rover cars - the very short-lived 10/12 of 1905 and the 16/20 of 1905-1910, for example, followed similar lines.

The former is remembered mainly for its monobloc 4-cylinder engine and the latter mainly because a slightly tuned version won the 1907 Tourist Trophy race. Within a month of the race a production model of the successful car was available; with a dashing Roi-des-Belges body and optional 4-speed gearbox, with geared up, or 'sprinting' gear, it sold for UK£450. Between 1904 and 1910 the emphasis was on reliability, economy of running, ease of maintenance and mechanical refinement. The 6 and the 8 were catalogued and indeed sold until 1912, little changed either in design or in price.

The first electric powered tricycle built and tested in Coventry, UK, in 1888. It was built by J.K. Starley of Starley & Sutton, the founders of Rover.

The first electric powered tricycle built and tested in Coventry, UK, in 1888. It was built by J.K. Starley of Starley & Sutton, the founders of Rover.

1906 Rover 8 hp tourer, powered by a single-cylinder 1327cc engine. It was the first serious production model manufactured by Rover, and one of these was driven by R. L. Jefferson from Coventry in the UK to Constantinople in a little over 6 weeks.

1906 Rover 8 hp tourer, powered by a single-cylinder 1327cc engine. It was the first serious production model manufactured by Rover, and one of these was driven by R. L. Jefferson from Coventry in the UK to Constantinople in a little over 6 weeks.

1910 Rover 8, which was fitted with a single-cylinder sleeve-valve engine.

1910 Rover 8, which was fitted with a single-cylinder sleeve-valve engine.

1926 Rover 9/20hp competing in the 1935 MCC Lands End Trials.

1926 Rover 9/20hp competing in the 1935 MCC Lands End Trials.

1912 Rover 12 hp. The 12 was first introduced in 1908 and was powered by a twin-cylinder engine.

1912 Rover 12 hp. The 12 was first introduced in 1908 and was powered by a twin-cylinder engine.

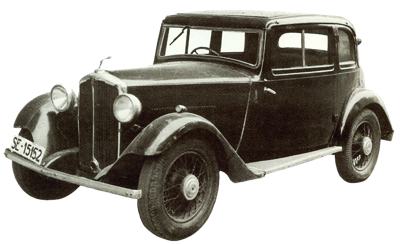

1932 Rover Pilot 14 hp six-cylinder version of the 10/25.

1932 Rover Pilot 14 hp six-cylinder version of the 10/25.

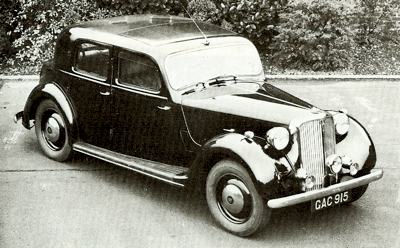

1940 Rover 16, which was manufactured between 1937 and 1940. It was fitted with a 2147cc six cylinder overhead-valve engine.

1940 Rover 16, which was manufactured between 1937 and 1940. It was fitted with a 2147cc six cylinder overhead-valve engine.

1948 Rover 60 four-light model, which was powered by a 1595cc four-cylinder engine.

1948 Rover 60 four-light model, which was powered by a 1595cc four-cylinder engine.

1951 Rover 75. It was powered by a 2103cc six-cylinder engine developing 72 bhp at 4000 rpm.

1951 Rover 75. It was powered by a 2103cc six-cylinder engine developing 72 bhp at 4000 rpm.

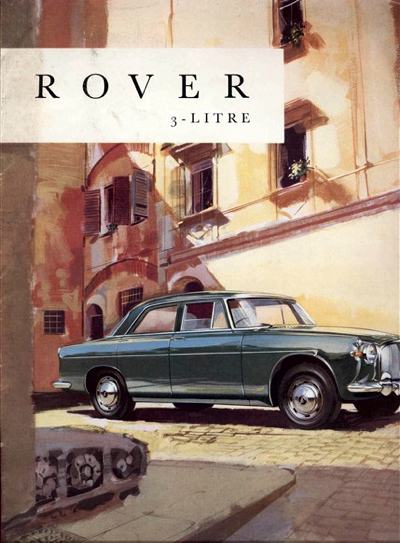

1958 Rover 3 litre, code numbered P5. These were in production until 1967, and were fitted with a 2995cc six-cylinder engine.

1958 Rover 3 litre, code numbered P5. These were in production until 1967, and were fitted with a 2995cc six-cylinder engine.

1961 Rover 100 Sedan, which came with a 2635cc six-cylinder engine developing 104 bhp @ 4750 rpm.

1961 Rover 100 Sedan, which came with a 2635cc six-cylinder engine developing 104 bhp @ 4750 rpm.

1961 Rover T4 Prototype, which was powered by a gas-turbine engine. The more conventional petrol driven Rover 2000 would be introduced 2 years later.

1961 Rover T4 Prototype, which was powered by a gas-turbine engine. The more conventional petrol driven Rover 2000 would be introduced 2 years later.

1962 Rover P5 3 Litre, which was fitted with a 2995cc six-cylinder engine developing 115 bhp @ 4250 rpm.

1962 Rover P5 3 Litre, which was fitted with a 2995cc six-cylinder engine developing 115 bhp @ 4250 rpm.

1962 Rover P5 3 Litre.

1962 Rover P5 3 Litre.

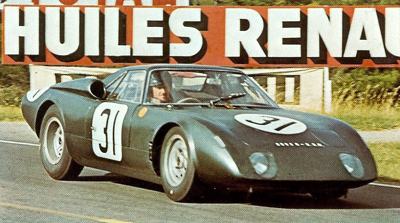

1963 Rover-BRM with Graham Hill at the wheel at Le Mans. This car averaged 108 miles per hour, and has the distinction of being the first turbine car to finish in a competitive race.

1963 Rover-BRM with Graham Hill at the wheel at Le Mans. This car averaged 108 miles per hour, and has the distinction of being the first turbine car to finish in a competitive race.

1967 Rover 2000TC, powered by a 1978cc four-cylinder engine developing 110 bhp @ 5500 rpm.

1967 Rover 2000TC, powered by a 1978cc four-cylinder engine developing 110 bhp @ 5500 rpm.

1971 Land-Rover Series III 88 Station Wagon.

1971 Land-Rover Series III 88 Station Wagon.

Rover 3500 SD1.

Rover 3500 SD1.

1977 Rover 2600, which was introduced along with the 2300 model as a cheaper version of the successful 3500.

1977 Rover 2600, which was introduced along with the 2300 model as a cheaper version of the successful 3500.

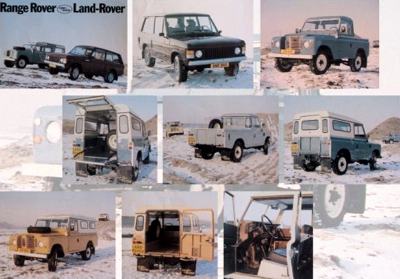

Land Rover and Range Rover.

Land Rover and Range Rover.

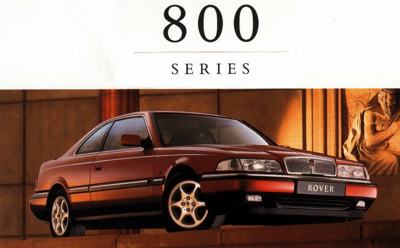

1998 Rover 800.

1998 Rover 800.

1999 Rover 75.

1999 Rover 75. |

The Rover Twin-Cylinder 12

In 1908 a twin-cylinder 12 appeared, still very much in the Lewis pattern though he was elsewhere and otherwise engaged by then. Its ball-bearing crankshaft was a potential source of trouble and even when a new 15 hp four-cylinder car was introduced in the same year with a plain-bearing crank, trouble continued because of deficiencies in the lubrication system. According to articles by another highly regarded Rover historian, John Pollitt (dec.), changing crankshafts was a regular thing. The designer of the 15 was Bernard Wright.

In 1905 The Rover Cycle Company Limited became The Rover Company Ltd. and in the same year the manufacture of motor-cycles was abandoned to enable car output to be increased. In 1910, however, Rover re-entered the motor-cycle industry with a new 3½ hp machine designed by J. E. Greenwood, highly thought of in its day (which lasted until 1921) and soon after cherished by connoisseurs. There had been rumours of a side-valve engined Rover beforehand (and Lewis had been busy in this direction) but the engine of the 3½ was in fact a straightforward poppet-valve single of 85 mm bore and 88 mm stroke.

It was a great success; 480 machines were built in its first year of production and by 1913 the total had risen to 1623. Production continued until the mid-twenties, but after World War 1 Rover's share of this competitive market gradually diminished, both in motor-bicycles and bicycles until their manufacture ceased in 1925. In 1910 two new cars were introduced - an 8 and a 12 with sleeve-valve engines of one and two cylinders respectively that had much in common with the power units of the contemporary 25 and 22 hp Daimlers. It is possible that the Daimler Company supplied components - perhaps complete engines; cylinder dimensions were shared, for one thing.

Owen Clegg

The sleeve-valve Rovers were quiet and popular little cars. They were at their best, it appears, in urban use. The next new Rover, which appeared in the autumn of 1911, was an altogether different proposition, as useable in town traffic as it was useful for long distance work; for the time it was an up-to-date machine that enjoyed immediate success simply because it was such an excellent motor car. Its designer was a Yorkshireman, Owen Clegg, whose experience before he joined 'the Rover' in September 1910 had been extensive. He was a master of works organisation, of planning for rapid and economical output on a large scale, and his four-cylinder 12 was a successful product of his ability.

Until Clegg appeared on the Rover scene, chassis had been built in small 'sanctions' and the number of different models had grown gradually over the years. His ultimate aim was to reduce the range, increase its maker's share of the market and enhance its reputation for quality. This he did within a year-a quite staggering achievement. By 1913 Clegg's 12 was the only Rover model on offer, the 18 hp car introduced along with it in 1911 having proved to be uncompetitive in its class. His 12 was the right car at the right time, with an extremely neat-looking 2.2 litre engine rated at 13.9 hp under the RAC formula. It qualified for the four guinea road tax in the UK yet its modest weight and medium size, in combination with a sweet but lively engine, allowed for adequate performance.

The Rover 12

The Rover 12 was an economical car to run - the price for the fully-equipped five-seater was UK£350, a remarkable figure at that time for a machine of such quality. It was one of the very best 13.9 hp cars ever made and once initial troubles with the worm-drive rear axle had been sorted its maker's only real problem was to meet demand. The design of the 12 was straightforward enough - an unusually tidy monobloc engine with

SU carburettor and Bosch magneto, a separate three-speed gearbox and final drive by open propeller shaft and underslung worm; suspension by long half-elliptic springs and braking on the transmission and on the rear wheels.

But mechanical subtleties were many and the result, as far as the sensitive driver was concerned, was highly satisfying. It was a quiet car yet a lively one; its controls were light and precise in their action and had a good 'feel'; it cruised without effort in the 30-40 mph range and could run up to 45 or so if necessary. For the 1914 season complete cars were sold with a 12-volt Rotax lighting set as standard equipment. The latter also included a one-man hood (for the tourer), windscreen, horn and spare wheel - items normally bought as extras at that time. There were 2 and 5 seater open bodies, the standard colours of which were buff or grey or green; a carmine Doctor's Coupe and a dark blue landaulette. The quality of body design and construction matched that of the chassis.

The Rover 12 not only raised the companies reputation to new levels - it increased its turnover, profits, dividends and cash reserves, and in 1914 a bonus of UK£15,000 was distributed to the staff. By then Clegg was sorting out the problems faced by Darracq in France. During the first war production of the 12 was stopped; apparently it was thought too small for official duties and its makers had to swallow their pride and build something like a thousand 16/20 Sunbeams for the Government, along with a number of Maudslay three-ton trucks. Motor-cycle production continued, along with cycle building and the making of much else in the munitions line.

J. Y. Sangster

It was decided to cater for two markets in peacetime - to re-introduce the 12 in improved form and to supply an economy car of low first cost to appeal to what might be called the new marginal motorists. As it happened a design and a

prototype for such existed and Rover wasted no time in acquiring these. Their creator was J. Y. Sangster, who was later to become an important figure in the English motor-cycle industry. Sangster's car was an

air-cooled, horizontally-opposed twin of 998 cc capacity, its bore and stroke - of 85 and 88 mm respectively - corresponding with those of the Rover 3½ hp motor-cycle.

Its J-Speed gearbox was in unit with the engine and final drive - even on such a cheap car - was by underslung worm. Its two-seater open body was stark but practical and durable, and the latter-day hard-top coupe was almost smart. The

steering wheel was ahead of its time, with two spokes only; accessibility throughout was good and adjustments easy-the owner-driver, it was anticipated; would do most of his own maintenance; 45 mph and 45mpg could be achieved (perhaps not together) and after early problems with the ball-bearing crankshaft and with overheating had been solved the Eight was a winner. Its perky appearance, its conical hub bed disc wheels, its wide track and its distinctive noises were still familiar in the early thirties. In 1919 its announced price was around UK£230.

By 1920 it had risen to £300. In the following year it had dropped, to £220; good value at that time of inflation. 1923 models cost £180 and in 1924 were down to £145. By then its day was almost over; competition from the recently introduced

Austin Seven, in truth a scaled-down 'proper' car, with a 4-cylinder water-cooled engine and attractive appearance, could no longer be ignored. The Tyseley works in Birmingham (specially equipped for the production of the Eight) were still busy but already plans were being made for a 4-cylinder water-cooled engine and a new, more up-to-date looking car.

The Clegg 12

Since 1919 the Clegg 12 had been made in some numbers in spite of considerable increases in price - in November of that year the provisional price of the 5-seat tourer was UK£750, more than double its 1914 cost. By 1922 it had dropped to UK£650, and a year later was down to UK£550 - with a 'Popular' model on offer at UK£450, minus clock,

speedometer, spring-gaiters and luggage-grid and finished in elephant grey. For 1924 it appeared as the 14, the tourer costing UK£495 with 4-speed gearbox, over 40 bhp, lower gear ratios and shock absorbers all round. Its production life was a short one, however; competition was stronger than ever before, the current Morris 'Oxford', a 13.9 hp car of exceptional qualities was available for £320, for example.

The Model T Ford was £110, and by 1924 the road tax advantage previously held by cars of smaller RAC rating was much less significant. Technically speaking Clegg's car was by now somewhat passe. His successor, Mark Wild, updated its specification after the Armistice only as much as was considered necessary to keep in line with the competition - mainly Vauxhall, Humber,

Sunbeam and Wolseley. But the company was busily developing a replacement for the 14. Before this was introduced, the

air-cooled engine of the Eight (which had been increased in capacity to 1130 cc to cope with ever-rising weights) was replaced in May by the new water-cooled Nine, an ohv unit of 1074 cc that developed about 20 bhp and weighed almost a hundred-weight more than its predecessor.

The Weymann system

At first there was little difference in appearance between the old and new models, apart from the presence of a real

radiator at the front end of the Nine instead of the dummy so long a feature of the Eight. Gradually the Nine assumed an identity of its own and two of the catalogued bodies - the Weymann saloon first seen in 1924 and the open Sports model introduced in 1925 - were of distinctive appearance. The Rover Company was quick to realise the advantages of the Weymann system, especially at a time when the average small car was underpowered and noisy. The light weight of a closed body built to the Weymann specification imposed a negligible penalty on performance and the absence of metal panelling largely eliminated the booming characteristic of most closed bodies of composite or all-steel construction until effective sound-damping was developed in the thirties.

Rover's coach building department, at Parkside, Coventry quickly solved the practical problems presented by Claude Weymann's system and bodies of this type were available on all chassis until the early thirties. Mark Wild's 3.4-litre six-cylinder car of October 1923 was Weymann bodied; perhaps it had to be because its stated power output of a little over 40 bhp was obviously insufficient for a car with a wheelbase of 11ft 5 in, a track of 4 ft 8 in, a lot of substantial mechanism that included a weighty four-wheel braking system and a heavy chassis. The engine was, in effect, a six-cylinder version of the Fourteen with a seven-bearing crankshaft (and no ball bearings), rated at 21 hp. Although it appeared at the 1923 Olympia Show, the fact that it was quietly dropped by its maker's suggests that it failed to attract sufficient orders.

Peter August Poppe

This was not the case as far as the successor to the Fourteen was concerned. Its designer was Peter August Poppe who joined the Rover Company in 1924.Poppe's 14/45 was a substantial car, of imposing appearance and conventional aspect. Like the earlier Eight, however, much of its mechanism was of an unusual kind. Its engine for example, was of the overhead-camshaft, overhead-valve type, with hemispherical combustion chambers. High efficiency might have been expected from such a specification but in fact its output of 45 bhp was little greater than that of the side-valve Fourteen and in service it lacked the reliability of its predecessor. Its complicated valve gear could be a source of unwelcome sound and poor fuel consumption was another common cause for complaint.

To some extent its maker's reputation was redeemed by raising engine capacity from 2132 cc to 2413 cc, which made an appreciable difference to performance, and the 16/50, as the new car was known, was well thought of by the trade, the press and owners. Of the latter there were not enough, however; since the end of the war the Rover Company had had its share of financial ups and downs and it was only because of the substantial reserves accumulated as a result of the success of the Clegg 12 that it was able to survive several poor years. The day was saved - temporarily, at least - by bringing forward a new and uncomplicated 2 litre model designed by Poppe and intended for production at a later date.

Although its premature appearance might have led to numerous teething troubles they failed to materialise in service and the handsome 6-cylinder car sold well in 1928 and 1929. Meanwhile the 9/20 had grown up, to become the 10/25 in 1928, but while its exterior appearance kept up with changing

automobile fashions the chassis and engine beneath were still of early twenties design. It was a difficult time for the motor industry, but the Riley Nine had already shown that creative design thinking could payoff in commercial terms. Unfortunately the Rover Company paid no heed until it was almost too late. New and forceful sales methods antagonised the dealers. Customers were annoyed, with a noticeable drop in quality control standards.

The Rover 2 Litre Light Six and Meteor Special Speed

Nevertheless good models were still being made. The clumsy looking 2 litre 'Light Six' was one; the proportions of its fabric covered, close coupled sportsman's saloon body were bad and its cycle-type mudguards somewhat out of character. Yet it went well, in a leisurely sort of way, its brown shape was a familiar one on British roads in the early thirties. An even better car was the 'Meteor' in its Special Speed sports tourer form, with cutaway door sides, louvred side valances, bonnet strap and eared knock-off hub caps. It was put together at the Segrave Road Depot with the Company's knowledge, and while they did not advertise it, Sydney G. Cummings, its joint distributor, most certainly did. Cummings had raced at Brooklands in the twenties and the design of the car was based on his practical experience. It could top 90 mph in open form, quietly and reliably, and owners included Major A. T. G. Gardner and J. K. Munday.

The Rover Scarab

The 'Meteor' was introduced in 1930 and its 2.5 litre six-cylinder engine was an enlarged version of the 2 litre. In that year there were 4 basic chassis - the 10/25, 'Light Six', 2 litre and 'Meteor' - but the number of body types and the variety of options available were unrealistic to market and administer. In 1931, when the Company was in an extremely unfavourable financial situation, with a deficit of almost UK£280,000, a new attempt was made to enter the small-car market. The Rover 'Scarab' was a four-seat open car with an 839 cc

air-cooled vertical V-twin engine mounted at the rear of its ladder-type frame, independent suspension for all four wheels, inboard rear brakes, a claimed top speed of 50 mph and a potential fuel consumption of 50 mpg. It was to be sold for UK£85 and a rather odd-looking van version was to be available at £99. The engine was also to be used in a crawler tractor intended for agricultural purposes. It was an intriguing project and at another time, perhaps, it might have been successful but Rover's uncertain future was a major reason for its abandonment, along with dealer disapproval and almost unbeatable competition from the current Austin 7 and Morris 'Minor'.

The Rover Pilot and Speed Pilot

The 1932 range included the 'Pilot', a 14 hp six-cylinder version of the 10/25, and the 'Speed Pilot', with a lowered frame and tuned engine. For the first time a wide selection of special bodies by outside coachbuilders was offered. The Company was also being quietly re-organised with great thoroughness. At a superficial glance the 1933 season cars differed little from their predecessors but the changes were many, improvements significant. Engines were now flexibly mounted, really quiet four- speed gearboxes were fitted; all models featured a freewheel, which made driving easier and more economical, and Lockheed hydraulic

brakes and Marles steering, which made control a matter of greater ease and precision. During 1933 Rover cars were to take part in rallies and at concours with plenty of success.

The Rover Speed 14, Speed 20 and Hastings Coupe

The coachwork competition in the. RAC Hastings Rally was won by a new model, a close-coupled four-seat saloon built by Carbodies that was added to the range shortly afterwards in 'Speed 14' and 'Speed 20' versions; the 'Hastings Coupe', as it was called, was much admired for its dashing look, its excellence of proportion, its comprehensive equipment and its lively performance. The fact that its frame passed below the rear axle meant that overall height was low and it is an interesting fact that its basic shape was to endure until the introduction of the P4 Rover '75' in 1949. Another fine-looking Rover of the time was the 'Speed Pilot' open tourer, which owed much to the 'Speed Meteor' of a year or two earlier. It could top 75, reach 60 from rest in 19 seconds (quick going in 1933) and stop in 28 ft from 30 mph.

The 1934 Rovers were introduced in August 1933. They were a distinct improvement on the previous cars, good as these had been; they were lower, wider, longer and even more distinctive in appearance. The 1388 cc 10 and 1496 cc 12 shared the same chassis and their new high-efficiency 4-cylinder engines had flexible mountings, counter-balanced three-bearing crankshafts and great rigidity among their many features. There were also three six-cylinder models-the 1577 cc 14, the 2023 cc Speed 16 and the 2565 cc Speed 20 - the engines of which were not new, their origins going back to the 2-litre Poppe design of 1927. The new 10, 12 and 14 shared identical bodies - a capacious 6-light saloon, a 2-door coupe similar to the 'Hastings', a 4-door sports saloon and a sports tourer, which made for manufacturing economies.

The Rover Streamline Coupe

From 1935 until 1938 the 10 was sold only in 6-light saloon form. During the 1935 season a special Streamline Coupe was offered on the 14 chassis. In 'Speed Model' form it was an 85 mph car - but a quiet and comfortable one. Its 'fastback' body was fashionable for a year or two only, striking appearance being offset by a lack of headroom in the rear. Between 1934 and 1939 Rover made few design changes to their cars. Automatic chassis lubrication was introduced for the 1935 season. Girling

brakes were standardised from 1936. All models for 1939 had a new

synchromesh gearbox but the freewheel was retained. In that year the 14 had a new 1901 cc engine, similar to the existing 16, a four-bearing crankshaft and down-draught carburettor being shared features.

The 1934 10 saloon cost £238, the 14, with the same body, £288. The corresponding models in 1939 cost UK£275 and £330 respectively. The wise policies initiated in 1932 were carried through with such success that the company had turned the old deficit of UK£280,000 into a balance of £560,000 by 1937. The cars made from late 1933 onwards had one thing at least in common with Owen Clegg's 12 - they were designed to be made economically. From the buyer's point of view that meant excellent value for money; for the company it meant that quality cars could be produced in quantity without any lowering of standards and at a good profit.

Manufacturing Aero Engines during World War 2

Rationalisation was something well understood at Rover. During World War 2 its involvement was complete, its main concern being with the production of aero-engines and, after intensive development work on jet-engines had been transferred to Rolls-Royce, with the building of the 'Meteor' tank engine. An important wartime decision led to the eventual closing of the Coventry plants and a concentration of activity in the Acocks Green and Solihull factories on the south-western side of Birmingham. Small scale production of the pre-war 10, 12, 14 and 16 models began towards the end of 1945 and in spite of all the problems of the time almost 16,000 cars were made during the following three years. At first only the 6-light saloon was available-in black, with brown upholstery-but before long the more attractive sports saloon was back and there was a short run of open bodies mounted on the 12 chassis.

Prices were up; the 10 now cost UK£588 instead of its 1939 figure of UK£275 and this doubling occurred throughout the range, but buyers were in no way put off. Once again the Company had snatched a little time from its warlike preoccupations to think of peacetime prospects arid while it was obvious that there would be a continuing sale for its medium-size quality cars it was felt that post-war fuel shortages might well stimulate a widespread demand ,for an economy car. Actual work did not begin until early in 1945 and from the start the aim was not to attempt to enter the low-price economy car market but to concentrate. on a miniature luxury car with low running costs.

The M1 prototypes that resulted were ingenious in design and it was a great pity that the idea was dropped - but materials supplies were uncertain, changes in the British road tax system were in the offing and in any case Government thinking then favoured production of medium-size cars. The M1 was tiny (its length was only 11 ft 4 in) and weighed 13t cwt, and as its 700 cc four-cylinder engine produced 28 bhp the power-to-weight ratio was a good one. Sustained cruising at its maximum of just under 60 mph would have been perfectly safe - something that could not be said of many small-engined cars in those days. Coil springs were used all round, suspension at the front was independent, and the frame was of the platform type.

The Rover P3

Early in 1948 the new P3 '60' and '75' models were announced and rationalisation was carried even " further-s-one chassis, two engines (a four and a six), two body styles. The latter were outwardly similar to their predecessors but incorporated a heating and demisting system. The new engines had overhead-inlet and side-

exhaust valves and were well-tried, prototypes having been in use since before the war. Independent front wheel suspension was used for the first time in a production Rover. There was little difference in price between the two; with either body type (4 or 6-light) the '60" cost UK£1,080 and the 6-cylinder car UK£1,106. They were the last of a long line of Rovers built on traditional lines - and many Rover die-hards we meet at car shows tell us they are the best.

The Land-Rover

The next new models were to be very different. The first was quickly on the scene; at the Amsterdam Show in April 1948 the

Land-Rover made an initial appearance that was followed by others. It was an all-purpose utility vehicle owing not a little to the wartime 'Jeep', intended for agricultural purposes, for use by anyone who needed a rugged, go-anywhere vehicle. Its engine was the 4-cylinder '60' unit, its gearbox was also from the car but had a second, 2-speed transfer box added, the drive was through the rear wheels on hard roads and through all four cross-country and its rigid frame carried an aluminium body. Suspension was by long and flexible half-elliptics - strong, uncomplicated and easy to repair or replace if necessary. At £450 in Britain it was always going to succeed - and demand immediately out-stripped production.

The Rover P4 75

Since 1948 the Land-Rover was developed in many ways but its basic design remained unchanged. It became an instant motoring classic, a mechanical immortal. The second new Rover was the P4 '75' introduced in October 1949, and the first of a line of cars of fundamentally similar design that remained in production until May 1964. Its engine and chassis differed little from those of the P3 '75' but were concealed by an up-to-date, full-width body, the look was not a hit with traditionally minded owners for some time. It was an impressively quiet car: it could reach 80 without fuss; it was economical, especially when the free-wheel was properly used, and its durability was to become legendary. In 1953 a 4-cylinder version, the '60', was announced along with the '90', a more powerful alternative to the '75'.

Roverdrive

For those who wanted to go even faster the '105S' first seen in 1957 was the biz, and for those who disliked changing gear there was the '105R', which had a reasonably good Rover-designed automatic box (called Roverdrive). For the 1960 season the range was drastically reduced; the '60' became the '80', with a sturdy 4-cylinder overhead-valve engine developed for the Land-Rover some time previously, and the '100' appeared - arguably the best of the 6-cylinder cars since

1950 - with a silky-smooth engine and a top speed in the high nineties. Disc

brakes and

overdrive were features of both models but the freewheel had gone.

The Rover P5

For 1963 and part of 1964 (production of the P4 ceased in May of the latter year) there were two 6-cylinder cars only - the '95', in effect the '100' with 3-litre instruments and without overdrive, and the '110', which had a Weslake-modified

cylinder head and induction system and was, perhaps, somewhat too fast for its chassis. In 1958 the P5 3-litre had been added to the range. It was lower and wider and costlier than its stablemates and its interior appointments were even more comprehensive and luxurious. Automatic transmission was available as an option; later on power-assisted

steering became available, as did a good-looking coupe; and throughout its life (and that of its successor, the 3.5, which was the same car, basically, but with a Rover-built, General Motors-designed V8 tucked inside its broad bonnet) found especial favour with users of 'official' cars.

The Rover 2000

But it was not simply a compact luxury vehicle; the 3-litre could take plenty of punishment, as several years of successful international rallying in factory teams had proved, and its handling, which was superior to that of the P4 range, gave it much greater appeal to anyone who liked to 'drive' their car. The new 2000 appeared in 1963 and altered its maker's image overnight. It was still a luxury saloon, but it was an exceptionally roadworthy car as well as a great drive. Safety features abounded in its design. Like the P5 its construction was of the integral type; its main feature was the use of a base unit to carry the mechanical units, electrical equipment, etc., accommodation for the occupants, wings, doors and other panels, and an extremely strong box-section bulkhead specially designed to deflect the engine from the driving compartment in a head-on collision, absorb front suspension loads and carry the principal parts of the

steering gear above and behind the engine.

The latter was a 90 bhp, 1978 cc four-cylinder unit with single carburettor, single overhead-camshaft and Heron head. Final drive was through a four-speed gearbox and open propeller shaft to a differential unit secured to the base unit; thence by swinging half-shafts to the rear wheels. The rear axle was of the De Dion type; coil springs were used front and rear and the front wheels were independently sprung. The engine was fed by single or twin carburettor (SC and TC) forms and as an automatic. It would grow in capacity to 2.2 litres. Yet its basic design had not been changed and its appeal to the keen driver was as strong as ever.

The Range Rover

From 1968 it was available with the V8 engine and - good as it was in its original automatic-only state - a manual-gearbox 3500S model was even better. The next entirely new model was the

Range Rover, first seen in 1970, and yet another instant success. It was (and remains) a large and extremely useful passenger and load carrier capable of almost 100 mph on hard roads and fast, exceptionally comfortable travel in less than ideal cross-country conditions - though, as a serious off road-vehicle, its capabilities were not quite up to those of the Land-Rover. For a period, the 2200 models were produced alongside the 3500 flagship but in 1977 they were dropped as the SDI bodyshell became available, with certain economies, with all-new straight six engines of 2.3 and 2.6-litre capacity.

In 1979, British Leyland began a long relationship with the Honda Motor Company of Japan. The result was a cross-holding structure, where Honda took a 20% stake in the company while the company took a 20% stake in Honda's UK subsidiary. The deal was thought to be mutually beneficial: Honda used its British operations as a launchpad into Europe, and the company could pool resources with Honda in developing new cars. Austin Rover Group was formed in 1982 as the mass-market car manufacturing subsidiary of BL, with the separate Rover Company becoming effectively defunct. In the 1980s, the slimmed-down BL used the Rover brand on a range of cars codeveloped with Honda. The first Honda-sourced Rover model, released in 1984, was the Rover 200, which, like the Triumph Acclaim that it replaced, was based on the Honda Ballade. Similarly, in Australia, the Honda Quint (known in Europe as the Quintet) and Integra were badged as the Rover Quintet and 416i.

BL Renamed As The Rover Group

By 1986, Austin Rover had moved to a one-marque strategy, using only the Rover brand. Its parent, BL, was renamed as the Rover Group, with the car division becoming Rover Cars. In 1986, the Rover SD1 was replaced by the Rover 800, developed with the Honda Legend. The Austin range were now technically Rovers, though the word "Rover" never actually appeared on the badging. Instead, there was a badge similar to the Rover Viking shape, without wording. These were replaced by the Rover 400 and Rover 600, based on Honda's Concerto and Accord, respectively. Then, in 1988, the Rover brand went back into private hands when the Rover Group was acquired by British Aerospace.

In 1994, British Aerospace sold the Rover Group, including the Rover, Land Rover, Riley, Mini, Triumph, and Austin-Healey brands to BMW, who had begun to see Rover-branded cars as potential major competitors. Under BMW, the Rover Group developed the Rover 75 as a retro-designed car influenced by the earlier Rover P4 and P5 designs. In 2000, BMW split up the Rover Group, selling Land Rover to the Ford Motor Company for an estimated sum of UK£1.8-billion, retaining the Mini operations, and selling the rest of the car business to the Phoenix Consortium, who established it as MG Rover. Although BMW included ownership of the MG brand in the deal, they retained ownership of the Rover brand, licensing its use to the new MG Rover company for use on the ongoing car models that they had acquired.

The Phoenix Consortium

A specially assembled group of businessmen, known as the Phoenix Consortium and headed by ex-Rover chief executive John Towers, established the MG Rover Group from the former Rover Group car operations (acquired from BMW for a nominal £10 in May 2000) and continued to use the Rover brand under licence from BMW. The year before its breakup, the Rover Group had sustained losses of an estimated £800-million. The four businessmen who took control of the newly formed MG Rover Group are reported to have received around £430-million in a dowry from BMW that included unsold stock.

The first new Rover-branded car to be launched after the formation of MG Rover was the estate version of the Rover 75, which went on sale later in 2000. In 2003, MG Rover launched the CityRover—an entry-level model that was produced in a venture with Indian carmaker Tata but failed to sell, as it was overpriced for the level of equipment if offered.[citation needed] Had MG Rover re-engineered and 'Roverised' the Indica to a higher degree and priced it more sensibly, it may have been much more successful. Several concept cars intended as eventual replacements for the Rover 25 and 45 were shown in the early 2000s, but never went into production.

MG Rover Production Ceases

MG Rover production ceased on 15 April 2005, when it was declared insolvent. On 22 July 2005, the physical assets of the collapsed firm were sold to the Nanjing Automobile Group for £53m. They indicated that their preliminary plans involved relocating the Powertrain engine plant to China while splitting car production into Rover lines in China and resumed MG lines in the West Midlands (though not necessarily at Longbridge), where a UK Research and Development facility would also be developed.

The Nanjing Automobile Group

On 30 May 2007, Nanjing Automobile Group claimed to have restarted production of MG TF sports cars in the Longbridge plant, with sales expected to begin in the autumn. Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation (SAIC), who held the intellectual property of Rover 75 car design (bought for £67m before MG Rover collapsed) and was also bidding for MG Rover, announced their own version of the Rover 75 in late 2006. In July 2006, SAIC announced their intent to buy the Rover brand name from BMW, who still owned the rights to the Rover marque. However, BMW refused their request, due to an agreement that Ford had reached with them to be given first option on the brand when it acquired Land Rover. Unable to use the Rover name, SAIC created their own brand with a similar name and badge, known as Roewe. Roewe was eventually launched in early 2007.

Also see: Rover Car Reviews